Executive summary

In this report, we examine twelve digital-born news media organisations across four different European markets: France, Germany, Spain, and the UK. The organisations covered include a mixture of domestic for-profit, domestic non-profit, and international players.

We find:

First, that European digital-born news media are clearly rooted in the profession of journalism. The organisations we cover are generally launched by journalists, often senior ones with experience of legacy media, and not businesspeople or technologists (and generally operating without the kind of major investment that has fuelled the expansion of some US-based international brands). Producing quality journalism or having social impact are more prominent goals than delivering digital innovation or building lucrative new media businesses.

Second, that digital-born news media are generally more prominent in Spain and France, with relatively weak legacy news media, than in Germany and the UK where legacy media remain strong. In every market, they are significantly smaller in terms of reach, revenue, and editorial resources than major legacy news media. New journalistic ventures seem to have found the most success where old ones are weak, rather than where digital media are most widely used or where the online advertising market is most developed.

Third, while different in some important ways, we find that European digital-born news media organisations are similar in many respects to legacy media. Some interesting journalism is being done, but the cases covered are generally not necessarily more innovative than leading legacy media in terms of their funding models, distribution strategies, or editorial priorities. This reflects their focus on journalism over business and technology.

Fourth, digital-born and legacy news media face very similar challenges online, especially around funding and distribution. In terms of funding, the online advertising market remains difficult for all content producers and progress with signing up subscribers is generally gradual. As a result, digital-born organisations are trying many of the same approaches – video, native advertising, various pay models, and commercial diversification – as their legacy counterparts. Firm figures are hard to come by, but the available evidence suggests most digital-born media are at best financially stable and not highly profitable. In terms of distribution, the shift from a direct relation between producer and users to one increasingly intermediated by search engines and social media represents the same combination of challenges and opportunities to digital-born news media as for legacy media.

Our more detailed analysis covers three related areas: funding models, distribution strategies, and editorial priorities.

We identify three different funding models, and discuss the opportunities and weaknesses of these models for different kinds of digital-born media. An ad-supported model is most prevalent amongst more established and older digital players who are aiming for wide reach, while newer digital-born news media have generally opted for a subscription-supported or donation-supported model and aim to serve more niche markets. All operate on a lower cost base than most legacy media, with smaller newsrooms, leaner organisations, and lower distribution costs.

In terms of distribution strategies, most of the organisations we look at are still in large part built around a website, whether for monetisation through advertising, subscriptions, or donations. All are working to leverage search engines and social media for wider reach and for promoting their journalism, but are also conscious of the risks of becoming too dependent on external platforms who may change their priorities over time. Several organisations highlighted the valuable role of email as a non-intermediated channel to communicate directly with readers.

Digital-born news media have different editorial priorities, but all seek to offer distinctive voices. Even the biggest of the organisations studied does not seek to replicate the full range of content of a print newspaper. While the bigger French and Spanish cases most closely approximate an online newspaper, they remain selective about the scope of their coverage. Other organisations focus more tightly on particular niches such as investigative journalism, where they feel they can bring a distinctive contribution. Social impact is a common aim, which is also in line with the campaigning tradition of many newspapers.

We find varying attitudes to legacy media amongst these digital-born news media. Some see themselves as competitors, others as supplements to industry incumbents, while the specialist investigative journalism organisations are happy to work in partnership with legacy media to break stories.

Introduction

Since the 1990s, a number of digital-born news media organisations have launched. These are news media organisations that are not simply digital extensions of legacy media organisations like the websites and apps of broadcasters and newspapers. Sometimes referred to as ‘start-ups’ or ‘pure players’, some of these have now been in operation for a decade or more and some no longer only operate purely digital operations. The sector is diverse and growing and the focus of this report. Generally, digital-born news media are smaller than legacy media in terms of reach, resources, and revenues. Because of the dynamics of the digital media environment, especially the intense competition between legacy media and large technology companies for attention and advertising, most are likely to remain so. But some have grown into impressive additions to the overall media environment, providing in-depth coverage of issues others ignore, giving voice to viewpoints marginalised elsewhere, and engaging more directly with younger people less loyal to legacy media.

A first wave of digital-born news media organisations was launched in the 1990s, most of them either content-based websites like Salon, Slate, and Netzeitung or portals like MSN, Yahoo News, and t-online that aggregated content from a range of sources and were tied in with other services like emails and search. A second wave of digital-born news media organisations has been launched in the 2000s in an increasingly digital media environment that is quickly becoming more and more shaped by search engines, social media, and the rise of mobile devices.

Across the two waves, the population of digital-born news media remains highly diverse. It includes both international players operating out of the United States, often in several languages (the Huffington Post, BuzzFeed, Vice, etc.) and domestic players operating in distinct national markets. In Europe, it includes organisations that have grown to rival some legacy media in terms of their audience reach and their editorial resources (like El Confidencial in Spain and Mediapart in France) as well as smaller niche-oriented and often specialised players (like Correctiv in Germany or The Bureau of Investigative Journalism in the UK). It includes advertising-funded, subscription-based, and donation-supported organisations, and both for-profit and non-profit organisations.

In this report, we analyse a sample of European digital-born news media organisations that are all built around news and public affairs. Beyond these, the digital-born content sector more broadly also includes a large number of organisations focused on fashion, food, health, lifestyle, popular culture, sports, technology, and travel, etc. Here we focus on those who invest in news journalism.

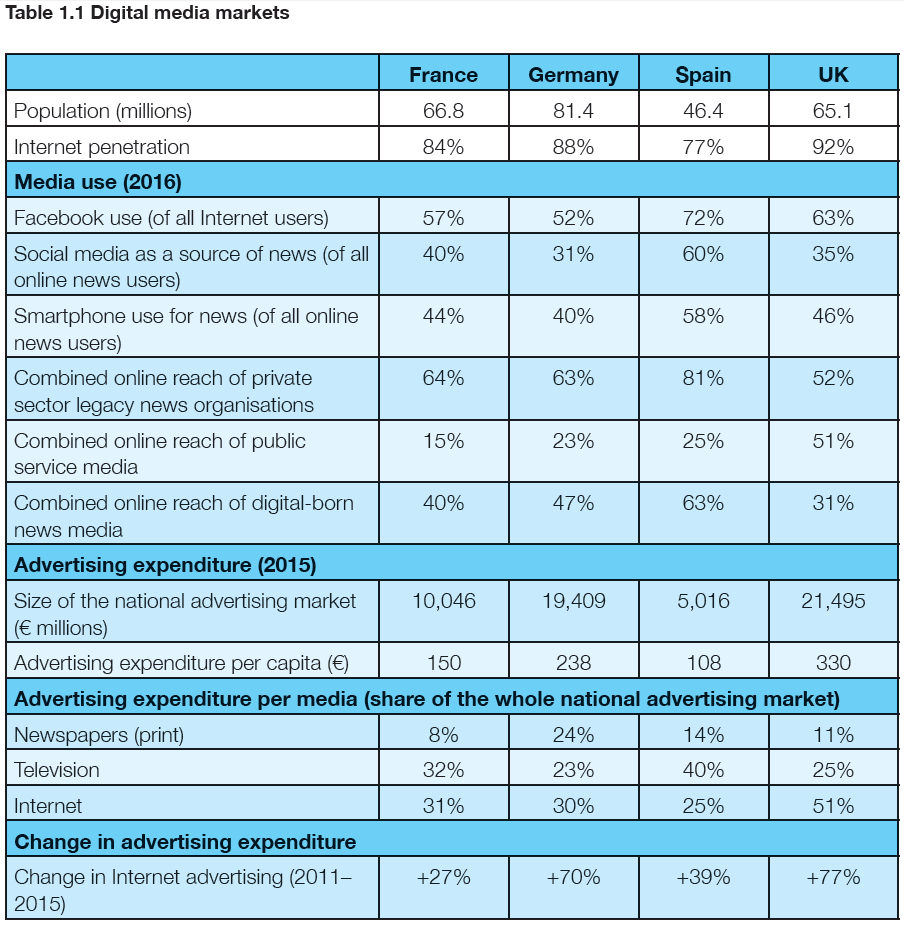

We examine cases from across four different European countries, France, Germany, Spain, and the UK, to capture variation both in different kinds of digital-born news media and in national contexts. France and Spain are examples of countries in which both private sector and public service legacy media were already relatively less robust before the rise of digital media and the impact of the Euro-crisis and where there has been a high number of new digital-born news media organisations launched in recent years (see Bruno and Nielsen 2012). Germany and the UK are examples of countries in which both private sector and public service legacy media have historically been stronger and where fewer digital-born news media organisations have been launched. In all four countries, digital-born organisations remain a relatively small part of the overall news media sector, and most of them are much smaller than established newspapers and broadcasters in terms of reach, editorial resources, and revenues (Cornia et al. 2016, Sehl et al. 2016). But they are important examples of how journalism can be done by new entrants building around digital media rather than legacy media. Table 1.1 provides context on the development of the digital media environment in each of these countries.

Source: Adapted from Cornia et al. (2016: 13). Data: World Bank (2016) for population per country in 2015; Internet World Stats (2016) for Internet penetration in 2014; Newman et al. (2016) and additional analysis on the basis of data from digitalnewsreport.org for Facebook use in 2016 (Q12a ‘Which, if any, of the following social networks have you used for any purpose in the last week?’), for social media use as a news source in 2016 (Q3 ‘Which, if any, of the following have you used in the last week as a source of news?’), for smartphone use for news in 2016 (Q8b ‘Which, if any, of the following devices have you used to access news in the last week?’), and for online reach of private sector and public service media in 2016 (Q5b ‘Which, if any, of the following have you used to access news in the last week?’); WAN-IFRA (2016) for size of the national advertising market (total advertising expenditure in € millions, exchange rates 1.36 GB£/€ 31 Dec. 2015) in 2015, distribution of that expenditure across media, and changes in Internet advertising expenditure 2011–2015.

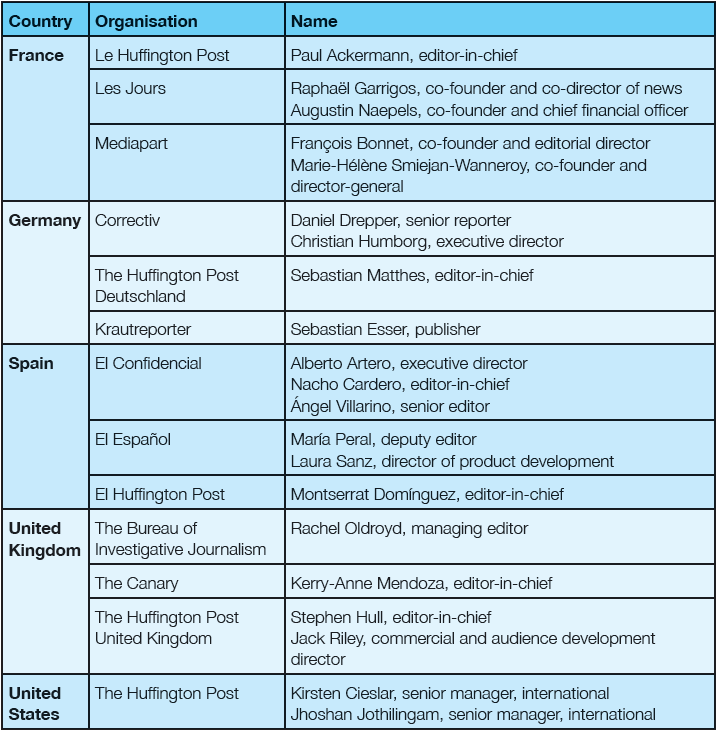

To better understand the editorial, distribution, and funding strategies of digital-born news media operating in different markets across Europe, we have selected a strategic sample of 12 case organisations across these four countries. Our ambition has been to cover a limited number of cases in more depth rather than more superficially discuss a larger number of organisations. In each country, we have selected two domestic digital-born news media organisations and one local edition of an international, US-based player. In each country, we have aimed to include examples of advertising-funded and subscription-funded, as well as for-profit and non-profit, digital-born media organisations to capture variation in both national context and organisational type. For consistency, we have examined the same international, US-based player, the Huffington Post, across all four countries. In September and October 2016, we conducted 21 interviews with senior editorial and business staff at these 12 organisations. A full list of interviewees can be found at the end of the report. Table 1.2 gives basic information on all the cases.

Sources: Journalist numbers from interviewees (excluding freelancers); reach data from ComScore (monthly unique visitors, September 2016).

The 12 organisations covered represent a strategic sample that captures a combination of different funding models (advertising supported, subscription supported, donation supported), distribution models (niche vs scale), and editorial strategies (focus on few investigative stories versus a broader range of coverage and a greater output).

Several of the domestic digital-born news media covered are launched by former high-profile newspaper journalists and sometimes refer to themselves as ‘digital newspapers’ or ‘online newspapers’. This includes El Confidencial in Spain and Mediapart in France, as well as the more recently launched El Español and Les Jours. All of these are private enterprises, and their overall strategy has clear overlaps with that pursued by many newspapers online (see Cornia et al. 2016). Other domestic digital-born news media are non-profits (The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Correctiv), co-operatives (Krautreporter), or political news sites (The Canary) that all generate some revenues but are run differently from a news business. Finally, our sample includes four of the first five international editions of the Huffington Post, all launched after AOL acquired the original US Huffington Post in 2011 and started investing in growing the site’s reach in a play for global scale that other US-based digital-born news media like BuzzFeed, Vice, and Quartz have since repeated.

The organisations we analyse represent a sample and not a survey of the complete population of digital-born news media in these four countries. We leave out some interesting domestic cases, as well as different editions of other prominent international, US-based players like BuzzFeed and Vice. The choice of countries also means we will not cover organisations elsewhere in Europe often brought up in interviews as inspirations – notably De Correspondent from the Netherlands.

Most of the 12 digital-born news media included in our sample have a basic commitment to the values of professional journalism, broadly understood as the independent provision of accurate, timely, and fact-based interesting and relevant news that help people navigate the world and be part of political and public life. Boxes 1–4 below provide short thumbnail portraits of four of our case organisations – Mediapart from France, Correctiv from Germany, El Español from Spain, and the Huffington Post, which operates across all these countries as part of its now 17 editions globally.

The scope of the different media organisations differs widely. Some, such as The Bureau of Investigative Journalism in the UK and Correctiv in Germany, are highly focused on one specific niche and present themselves as a supplement to legacy media. Others, such as El Confidencial and the Huffington Post, take a much wider view and aim to cover a broad range of needs and interests, in the spirit of a general online newspaper, and often compete much more directly with legacy media. As François Bonnet, editorial director and co-founder at Mediapart in France says,

Our competition is Le Monde, Libération, Le Figaro, Les Échos when it comes to some economic investigations. We have 122,000 subscribers. Libération sells 25,000 copies in the kiosk. Le Monde sells 230,000 in all, like Le Figaro.

In contrast to that competitive stance stands the collaborations sought by, for example, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, where managing editor Rachel Oldroyd actively seeks to find partners to co-publish their work: ‘The first port of call in our work would be in the Guardian or BBC or whoever our publishing partner is.’

What we examine in the report is how digital-born media deal in different ways with the challenges of doing such journalism, distributing it, and funding it. What they have in common across the differences in how they are organised and in terms of the national markets they operate in is that they operate without the liabilities and assets of legacy news media organisations like newspapers and broadcasters.

First, unlike legacy media, digital-born organisations are native to a digital environment. Though they too face the challenge of constantly adapting to a continuously changing environment, they do so with less of the inertia and often a leaner organisation and cost structure than that which comes with having a longer history and a more entrenched set of organisational structures, business practices, and professional norms (Bruno and Nielsen 2012, Küng 2015). They are therefore in some ways better positioned to focus on future opportunities without having to also manage inherited operations that often inhibit change.

Second, however, digital-born news media organisations also have to establish themselves without the assets that legacy media have, including brand reputation, loyal audiences, and revenues generated by print and broadcast activities (Cornia et al. 2016, Sehl et al. 2016). They therefore have to fight for attention and live only off their digital operations as they cannot rely on subsidies from legacy operations to fund investments in digital initiatives. Looking broadly beyond news media, it is worth remembering that the majority of new businesses fail and most of those who succeed take years before the break even.

In the rest of the report, we examine how a sample of digital-born news media organisations in Europe are developing funding models (Chapter 2), distribution strategies (Chapter 3), and editorial priorities (Chapter 4) to provide news in a changing media environment, before turning to a concluding discussion of digital-born news media in Europe. We show how, despite their clear differences from legacy media organisations and the very real opportunities presented by the growing digital media market, they in fact face a number of very similar challenges, especially in terms of finding sustainable funding models for digital news production and in terms of dealing with the opportunities and risks offered by digital intermediaries. Digital-born and legacy news media alike are aiming to sustain themselves in a very competitive market with pressure on advertising revenues, limited growth in the number of people paying for digital news, and without much of a tradition of support for news production by foundations or non-profits.

Mediapart, France

Founded in 2008 by Edwy Plenel, a former editor-in-chief of Le Monde, Mediapart’s team of journalists come from a diverse range of media backgrounds, including newspapers like La Croix and Les Échos as well as news agencies such as Reuters. The site is famed for its journalistic scoops and is cited as a global example (also by other subscription-led models in this report) of how a subscription-led business model works for digital-born media. ‘The foundation of Mediapart is investigative journalism, which had been abandoned by other medias for economic or political reasons. Creating a difference is about more scoops and having ideas others don’t,’ says François Bonnet.

Subscriptions account for 96% of revenue, via a combined total of almost 130,000 paying subscribers. The site is split into two parts online: its own professionally produced journalism, often long investigations of powerful institutions in politics or business, and ‘Le Club’. Bonnet calls this the ‘heart’ of Mediapart’s editorial concept. Every subscriber automatically gets a blog, and this network posts about 35,000 articles a year, from which Mediapart selects and features the top 15 every day.

Correctiv, Germany

Founded in 2014 with €3m from the Brost Foundation to cover the first three years of operation, Correctiv is a non-profit investigative newsroom, focusing on socially important stories that are in the public interest. As Christian Humborg, executive director, puts it, ‘We believe that we need a new era of enlightenment with a capital E.’ In addition to publishing the results of their investigations online, Correctiv partners with legacy media to publish stories and also experiments with innovative forms such as stand-up comedy and journalistic comic books to get across the results of its investigations. The site is registered as a non-profit in Berlin and is developing a funding model based largely on raising donations from readers and charitable foundations, supported by a range of revenue-generating activities such as events and book publishing.

El Español, Spain

El Español was launched in 2015 by Pedro J. Ramírez, a high-profile journalist who became editor-in-chief of the newspaper Diario 16 at the age of 28 in 1980, just after Spain’s transition to democracy. In 1989, he co-founded the newspaper El Mundo to continue his work on Basque terrorism and investigations into the role of the government. Ramírez was fired in 2014 after being accused by conservative prime minister Mariano Rajoy – whom his paper had endorsed on three occasions – of ‘slander’. Ramírez says El Español is the first media born in the twenty-first century ‘which is thinking about the twenty-second century’.

With an investment of €6 million from Ramírez himself, more than €3.5 million raised from over 5,000 investors (who become shareholders) in a six-week crowdfunding round, and €8.4 million from institutional investors, El Español aims to diversify subscription and advertising revenue with e-commerce or e-learning, and aims its readership at young, urban professionals. ‘People were tired of seeing the same news every day, which didn’t push people to know more,’ says deputy editor María Peral. ‘It was appealing for them, to want to change this.’ Ramírez’s new site is critical of the political establishment in Spain and he has not hidden its support for the emerging centre-right political movement, Ciudadanos.

The Huffington Post

The Huffington Post is a US-based media company originally founded in 2005 by Arianna Huffington, Jonah Peretti, and Ken Lerer as a liberal media platform in response to George W. Bush’s re-election and the perceived dominance of right-wing media online. After being acquired by AOL for $315 million in 2011 (in turn acquired by Verizon in 2015), the site began to expand, first to Canada and the UK, and has since launched 16 different editions publishing more than 1,500 articles per day. The site broke even in 2010 on revenues of $30 million, and has since invested heavily in its global expansion. In 2015, it was reported to have broken even again on global revenues of about $150 million and reaching 200 million monthly unique users globally. In 2012, it won a Pulitzer Prize in National Reporting for a 10-part series on the lives of severely wounded veterans and their families.

Many of its international editions are launched in partnership with national media. Le Huffington Post launched with Le Monde in 2012; months later in Spain, El Huffington Post launched with El País. In 2013, HuffPost Deutschland launched with Tomorrow Focus, which runs focus.de, Germany’s third largest German news portal (and is part of the privately-run Hubert Burda Media conglomerate). The partner media and Huffington Post US are there to support development of the individual editions, which all share a strong native content model. ‘Huffington Post has a voice and a mission,’ senior manager (international) Jhoshan Jothilingam explains, but ‘we didn’t know the ins and outs of national media, so we have traditionally partnered with companies who believe in our culture and with digitally focused newsrooms that aligned with us. Given their local knowledge, they are influential in helping us to understand the media ecosystem in their market.’

Funding Models

All digital-born news media organisations need to find a way to cover their costs, to sustain themselves and invest in their journalism. But the forms of funding they rely on and the models behind them vary.

Some are private for-profit enterprises, like Mediapart, Les Jours, El Español, El Confidencial, and – though it is in part politically motivated – the privately incorporated The Canary. All four editions of the Huffington Post are subsidiaries of a publicly traded for-profit enterprise. The remaining cases we cover are non-profits (The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Correctiv) or co-operatives (Krautreporter).

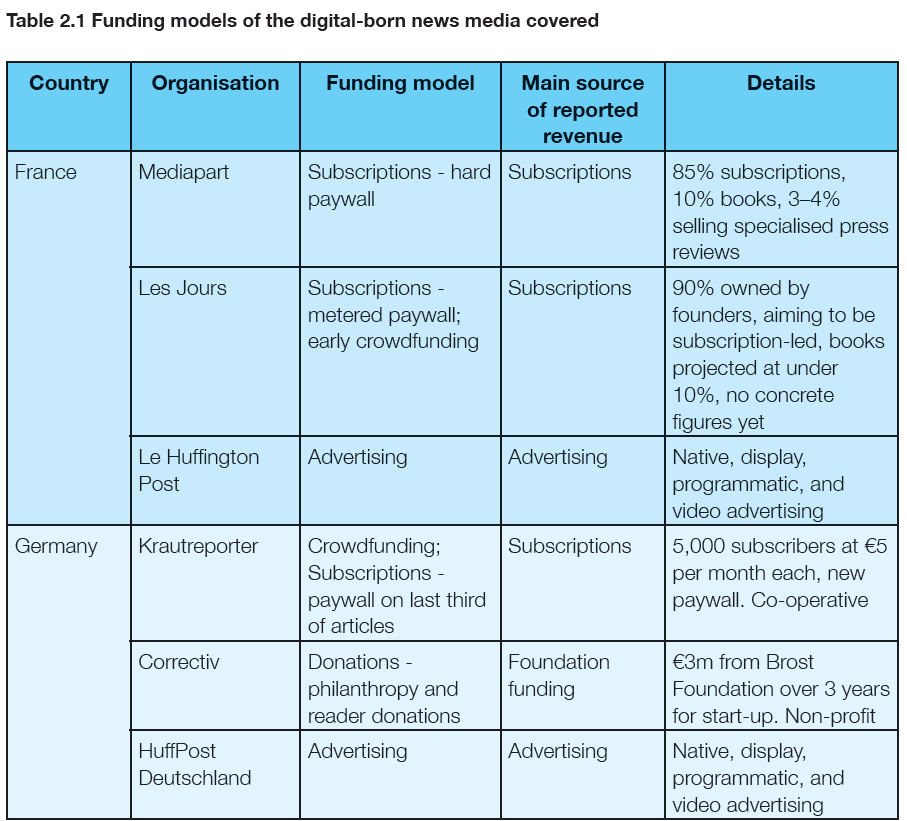

Their funding models vary too. El Confidencial, the oldest domestic digital-born news media we look at here (founded in 2001), and all four editions of the Huffington Post are funded primarily by advertising. Mediapart, Les Jours, and to a lesser extent El Español rely on subscriptions. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, Correctiv, Krautreporter, and to a lesser extent The Canary rely at least in part on donations (see Table 2.1).

There is a clear contrast between the advertising-supported sites, which are older, and those that rely on subscriptions or donations. A number of digital-born media organisations directly challenge the idea that digital advertising alone can fund quality journalism today. Krautreporter’s publisher Sebastian Esser says:

[Advertising] doesn’t make enough money for the good kind of journalism. … I really think that in the long run, [getting your readers to pay] has to be the only thing that can work for journalism … because why would you take money if you want to be really independent from other sources?

El Confidencial (as one of the biggest digital-born news media in Europe) and the Huffington Post, with its global reach, challenge the strong stance on advertising, but it is clear that the majority of the more recently launched digital-born news media we examine here are betting on subscriptions and donations from readers or from foundations, as well as additional revenues from spin-off activities such as books and events, and not on advertising.

Below, we go through examples of advertising-funded, subscription-funded, and donor-funded approaches in turn, before discussing other sources of revenue being explored by digital-born news media.

Advertising-Based Models

Advertising constitutes most of the revenues for every Huffington Post edition. In Spain, it’s the primary source of revenue for El Confidencial (90% programmatic and native advertising, 6% events) and El Español; the latter, while working hard to build a base of paying subscribers, is currently primarily making money from traditional display advertising, native advertising, and events. With a funding model mainly based on advertising, El Confidencial says that ‘economic freedom and profitability’ are its advantages over competitors in aiming to be ‘a leader in quality’ and ‘agile’.

On the advertising-funded sites, there is a concerted effort to move away from display advertising, where rates are under pressure from the move to programmatic advertising sales and from competition from large technology companies, towards new native advertising formats and online video advertising. Alberto Artero, executive director at El Confidencial, says,

Our most important source of revenue today is still advertising, to tell you the truth. We have two sources: pure advertising, which is programmatic, and native advertising, an area in which we invested this year and which is [making] a lot of money. We also organise some events, but events (like round tables) are less than 10% of the whole turnover. The industry we are looking towards is via brand content, events, even subscription. We have a high cash position; we don’t have debt. We’re making money.

There is a clear link, for the advertising-supported digital-born media we interviewed, between the editorial positioning of the site and the opportunities for generating advertising revenue. With rates for programmatic advertising falling, there is a strong incentive to produce distinctive content to support direct (and premium) sales of advertising inventory and to improve the environment for selling native advertising.

The Huffington Post says it is ‘passionate’ about content which advertisers find attractive, including solution-based reporting and issues such as parenting or sustainability. Day-to-day sales in France, Germany, and Spain are handled by partner organisations. ‘We leverage our 11 years of digital-first expertise, that local editions then put into practice,’ says Kirsten Cieslar, senior manager (international) at the Huffington Post; ‘they then take their existing relationships, market knowledge, organisation, and are able to put it to work.’ Jhoshan Jothilingam, senior manager (international) adds,

Our partners naturally know the ins and outs of their market in say India, or France or Germany … and help us understand the ecosystem and Huffington Post’s niche in that market. Their sales teams further that local expertise … and bring connections and understanding of the different elements of the advertising landscape.

Laura Sanz, director of product development at El Español, says that as an ‘influential media’ they provide ‘good visibility’ and select advertising formats with this in mind. ‘We want readers, but also brands, to pay for good content – we don’t sell any intrusive advertising.’ In the UK, The Canary uses multiple forms of advertising (display, programmatic, native, video) as well as voluntary subscriptions in order to sustain its free news distribution.

How can investigation-focused media remain viable, taking advertising while publishing material that may challenge advertisers? The challenges for digital-born news here mirror those of their legacy predecessors. Ángel Villarino, senior editor at El Confidencial, admits it can be hard and points to a version of the traditional separation between news and business staff, coupled with a particular appetite for this content in Spain:

Very often our investigative journalism makes it more complicated for our sales department to find advertisers, but our publishers never put that pressure on the newsroom. Our job is simple and clear: reach more readers with more and better journalism. We probably upset some companies and lose advertising often but, on the other hand, we have more and more readers every month. This model probably would be impossible in many other European countries where the media market is more mature. Here in Spain there is a real thirst for real journalism.

The Canary take a resolutely pragmatic approach towards advertising, seeing it as a core way of funding their mission of broadening the breadth of news coverage. As the site has grown, they have taken the opportunity to move to more lucrative approaches, from programmatic advertising at the beginning to a broad portfolio of different advertising methods now. As Kerry-Anne Mendoza, editor-in-chief, explains:

We started off like every website starts off which is Google AdSense. Very easy – you add your little toggle and off you go. But because of the way that our readership expanded in the year it obviously got more attention from advertisers, which means even in Google AdSense – and we have got several other servers now which are creating income lines for the site – it means people are bidding higher for each unit that we have got on the website. So we are seeing the CPM and RPM go up through that period of time, and an increase in the number of advertisers. So we started off with AdSense; we have now got video advertising, native advertising, and one of the leadership team is specifically devoted to advertising.

Several digital-born news media are particularly interested in developing their native advertising (also variously described as sponsored, branded, or custom content) business. Like many legacy media, they see native advertising as a way of providing a premium product to advertisers that is clearly distinct from commodified display advertising bought programmatically through ad exchanges and is a format that is likely to offer much higher rates (Cornia et al. 2016).

Both El Confidencial and El Español have invested in native advertising this year, and both corroborate that it is a fast-growing sector in Spain. For each of the Huffington Post editions, native advertising is an important and growing part of their advertising mix.

As in legacy media, this development is seen as one that has to be handled with care to avoid blurring the line between editorial content and native advertising. A prominent theme was the importance of disclosure and the separation of branded content from regular news coverage. Kirsten Cieslar at the Huffington Post says,

We clearly disclose native, or brand sponsored, content across the site. It’s always very clear to our readers that they’re reading content created in partnership with the brand. … We’ve done a number of studies that show that the majority of Huffington Post users don’t really care if content is sponsored, so long as it’s good content.

Several media, including El Confidencial, El Español, and the Huffington Post, have enforced strict separation between the two operations, reinforced by prominent marking of sponsored content on the website. Stephen Hull, editor-in-chief of Huffington Post UK, calls it a ‘church and state’ arrangement: ‘AOL’s commercial content business is called Partner Studio, and the fundamental thing is that journalists who work in the Huffington Post never touch commercial or sponsored content.’

As a consequence of this, all the digital-born news media based around advertising in large part seek a wide audience and embrace most forms of distributed discovery and distributed content via search engines and social media in the pursuit of it (more below). Editorially, they generally produce more content and cover a wider variety of topics than subscription- and especially donation-based sites.

Subscription-Based Models

Outside the highly competitive English language market, a growing number of digital-born news media are developing subscription models. Different organisations are using different models for reader payment, including hard paywalls, metered paywalls, and paywalls to read whole articles rather than excerpts, as well as pay models tied to the provision of exclusive services not narrowly tied to news content (a mobile app, access to a behind-the-scenes area on the website).

The French site Mediapart is the trailblazer for subscription-based digital-born news media. Their ‘initial bet’ that they could get 50,000 subscribers to pay for independent news within three years paid off. Today 96% of revenue is from subscriptions: ‘We didn’t wake up one morning saying “We’ll be paid for from subscriptions”, but we said a daily media has to be independent from capital and independent in its revenues,’ says Marie-Hélène Smiejan, co-founder and director-general of Mediapart.

As of late 2016, Mediapart has almost 123,000 individual subscribers or ‘net active payers’. With a further 5,000 collective subscribers (companies, government organisations, etc.), there are almost 130,000 paying subscribers in total. The site has experienced considerable churn in its subscriber base, explains Marie-Hélène Smiejan – ‘There are 360,000 people who have paid for Mediapart at least once’ – but also continues to attract new paying readers. ‘There is not a single day where we haven’t recruited new subscribers; we always have done, every day – 100, or 300, 600, or 1800.’ Mediapart argues that their investigative scoops have been key to attracting subscribers. ‘Yesterday we published a huge scoop on Sarkozy, and got 300 new subscriptions,’ says François Bonnet. ‘After the story was repeated on evening television, we saw a new peak in subscriptions. I’m obsessed with checking subscriptions. You see an immediate impact.’

Other digital-born news media in Europe explicitly mention Mediapart as an inspiration as they aim to develop their own subscription model. At El Español, a reader gets access to 25 free articles a month (compared to ten at, for example, the New York Times) and activates an €11 a month paywall after that, or €6 a month if the reader signs up for an annual subscription. Once beyond the paywall, El Español subscribers can access the subscribers’ zone ‘La Edición’, where there are deals with Amazon, to buy e-books, and so on.

All the subscription-based media showed concern for the quality of reporting as a key reason why subscribers could be persuaded to pay. ‘Spanish people are spoilt,’ says María Peral, deputy editor at El Español. ‘They do not pay for news. We have no problem with our audience numbers, so our problem is to convince our audience.’ El Español, who argue they are ‘pioneering’ pay models for Spain, say that the pace of growth in subscriptions (currently at 13,900) is slowing down, but they are confident it will be central to their model moving forward. In a steering committee video from June 2015, El Español’s CEO Eva Fernandez presents a list of paywall-modelled medias in the world, with Mediapart on the list, and says: ‘They have a value, which has a cost, which has a price.’

Similarly, in France, the newly-launched Les Jours is betting on subscriptions as part of its vision ‘to be at the forefront of a kind of second wave of pure players in the French market, more in tune with how we can do digital media’. Raphaël Garrigos, co-founder and co-director of news, calls Mediapart a ‘big brother’ – ‘Mediapart has shown that people will pay for news’ – and has adopted its subscription-only funding model. Les Jours is focused on delivering original content and a good product, and hopes that a good user experience and design functionality can give it an edge: ‘We’re in an era where people pay for news but also music, TV shows,’ says Raphaël Garrigos. ‘We were inspired by Netflix, Deezer, and Spotify when we were creating our website, rather than other news websites.’

The co-operative site Krautreporter in Germany is also building a subscription base, though one they cast in less commercial terms. Sebastian Esser clarifies:

We’re not selling content. We’re building a relationship and then asking them for money, which also means that not all of them will pay. … We tell our colleagues that usually just 5% of your community will pay if you ask them right, but it’s a completely different business model from the usual paywalls where you think that your content is so unique and so great that you can charge money for it.

Paywalls are not necessarily fixed, even for organisations with subscription-based funding models; several sites have introduced paywalls, or changed their criteria, in light of experience. Krautreporter have recently put in place a paywall which restricts the last third of each article to subscribers, with Sebastian Esser noting: ‘We’ve experimented a lot with it; the basic model at the beginning was everything is free for everyone to read, but we ask people for contributions just because they think it’s important and they want to be a part of it. We’ve started pushing up the paywall a little bit, because we just need to convert more people and we realised it works.’

Across the countries and cases covered here, there seems at least to be a clear shift away from primarily relying on advertising to find digital news production towards a greater interest in building subscription models. Even El Confidencial, which has operated for 15 years on the basis of advertising, is saying it would love to experiment with subscription. Alberto Artero notes: ‘We think some groups of people will be willing to pay to get the news earlier than others.’ The idea of subscriptions was met with scepticism when the model was introduced in 2008 in France, says Marie-Hélène Smiejan: ‘French pseudo-intellectuals said paying for information online wouldn’t work because the Internet is free, it’s the foundation of the Internet itself,’ but it has worked for Mediapart, and others are seeking to follow their example.

All the subscriptions-based digital-born news media sites focus on developing an editorial product that stands out in a crowded marketplace. They embrace distributed media for discovery and to market their content, but seek conversion to paying subscribers to sustain their business. Their editorial priorities are often more focused on a limited number of more in-depth articles.

Donation-Based and Crowdfunding-Based Models

A third funding model is to rely on voluntary donations from foundations and individuals who believe in the editorial product, not as a fee for service (as in a paywall model) but as a contribution to a public good. Several of the organisations in our study are attempting this model, relying on philanthropic foundations, crowdfunding from the general public, membership schemes, or a combination of these.

Crowdfunding campaigns operate in a space somewhere between the paywall-based commercial model and the giving of voluntary donations. For launch funding, organisations can either offer an equity share in the business or simply take subscription payments up front for the first year (which, depending on the existence of a paywall, may be an advance on a fee for the service or simply a possibly recurring donation). In both cases, the pay-out is uncertain and in the future, rather than in access to paywalled material now.

One of the pioneers in the crowdfunding space is the Dutch website De Correspondent. In 2013, it set a funding record for crowdfunded journalism by raising more than €1 million from over 15,000 people in eight days. These donors were signed up for a one-year €60 subscription, providing not only the initial funds to start the site, but also a base that De Correspondent has since expanded to a reported 47,000 paying members.

Several sites covered here, including Krautreporter in Germany, Les Jours in France, and El Español in Spain cite De Correspondent as an inspiration. All of them started similar crowdfunding rounds before launching, but with wildly different results. Krautreporter mobilised over 15,000 members who contributed just under €1 million in total when they launched in 2014, but as of 2016, the site is down to about 5,000 paying members who support the site on an ongoing basis. Les Jours launched with considerable media attention as several people involved had just left the newspaper Libération. They launched their campaign seven months before the site went live to build a community around the project, and continued to keep them informed throughout. They reached their target of €50,000 in one week by signing up 1,500 subscribers before the site launched, and €80,000 was raised in total – ‘not at De Correspondent’s level,’ says Augustin Naepels, co-founder and chief financial officer at Les Jours, ‘but for France it is unusual to raise such a high sum.’ After six months, Les Jours had 6,000 subscribers, with a target to get 8,000 subscribers by the end of the first year and an eventual aim of reaching 25,000 to sustain an editorial staff of around 20.

El Español, which also drew attention because of Ramírez’s exit from El Mundo, raised a world record €3.6 million from 5,624 individual investors during a six-week equity crowdfunding campaign prior to launching in 2015 (Nurra 2015). María Peral explains how the combination of a high-profile editor-in-chief and a clear mission to be independent of the establishment and provide an alternative to the churn of everyday news helped the site:

Pedro J. is successful because he discovered many things about our Spanish history. When El Mundo published on the the government’s illegal party finances, he was fired. Even if you don’t agree with him, you have to recognise his work in changing our country. We have certain ideas for changing our country and reforming institutions.

A variation of the crowdfunding and member-oriented models is a focus on raising money from charitable foundations rather than the general public. This has been particularly favoured by non-profit media organisations focusing on investigative journalism, following the path trodden by US non-profit media like ProPublica and state- and local-level sites like the Texas Tribune and MinnPost (Jurkowitz 2014). The Bureau of Investigative Journalism in the UK and Correctiv in Germany both took this approach, using multi-year, multi-million grants from large foundations as a way to get established and fund the early stages of long-term investigations. Rachel Oldroyd at The Bureau of Investigative Journalism says,

It is really difficult to do this without that initial deep-pocketed funder, who is generously prepared to just go ‘Okay, five years, just get on, do what you can.’ Once you’ve established a certain brand, a degree of work and had some good stories, it is easier to go to funders.

A key issue with dependence on major donors is vulnerability to grants not being renewed. Each of the organisations initially founded with major grants was clear that there was a need to broaden the base of funding. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism is continuing with the philanthropy model, approaching other charitable trusts to fund particular projects. Correctiv are gradually shifting to a broader, donation-based model. Christian Humborg says, ‘We needed to become independent from the Brost Foundation very quickly, because we don’t want any dependency and we have to stand on our own feet.’

For news media hoping to pursue philanthropy or crowdfunding as a funding model, the national context is hugely important. The US is known for having a substantial base of foundations prepared to fund public-interest journalism, while in France such foundations are unknown. In the United Kingdom and Germany, the quality of existing public service and legacy media makes it difficult to persuade citizens or foundations to donate for journalism per se, but there are opportunities for the funding of particular areas of focus, as Rachel Oldroyd at The Bureau of Investigative Journalism explains:

If we find an area that is just not being covered properly, that is so worthy of being covered, like antibiotic resistance, then we can go to funders who cover that specific area, and then we have to persuade them that journalism should be part of their mix. So, rather than coming in and saying “Please fund an investigative journalism project”, you’re saying “We want to do this work which is in your remit”.

Some examples include the following:

- Affiliate marketing and e-commerce partnerships, pursued by the Huffington Post US and El Español (who are also pursuing ‘e-learning’), where readers are referred to online shops and the site receives a fee in return if a sale is made. The Canary also does this with book recommendations at the bottom of articles that they argue help their readers read more deeply into a topic while also providing an additional revenue stream.

- Syndication of content, pursued by both The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Correctiv, who sell some of their news output to legacy media outlets. In both cases, the money generated is, however, limited, and Rachel Oldroyd, from the Bureau, says that impact is more important than the sums involved: ‘We’d much rather use a publishing partner to help us with reach, with contacts, and with readers and eyeballs. And we’d rather negotiate whereabouts it’s placed in the position in the paper and the day, etcetera, than [they] pay us a couple of thousand pounds.’

- Information services, which El Confidencial offers in the Spanish market on the basis of their business reporting. Similarly, both Correctiv and The Bureau of Investigative Journalism are looking with interest at the various funding streams being pioneered by US non-profits in this space, especially ProPublica’s monetisation of databases created in the course of investigative journalism.

- Publication of hard copies of content with a long shelf life, something built into Mediapart’s strategy from the outset. Because the site publishes more in-depth articles which stay relevant over time, says Marie-Hélène Smiejan, it can publish and sell hard copy books, a quarterly review, and e-books: ‘We do less of them now but one enormously read one was an A–Z analysis of the Front National’s programme in 2012. It’s a content production with a different reading rhythm or for a different audience.’ Les Jours has published an investigation into the privatisation of the French broadcasting sector with the prestigious French publishing house Seuil within six months of launch. Correctiv’s handsomely bound ‘bookzines’ contain printed versions of their stories, produced every few months, and are both sold separately and distributed to members to help retain them. A recent printed spin-off is Weisse Wölfe, an investigation into German far-right terror groups reported in comic book form.

Funding Digital-Born News Media

Digital-born media are continuing to experiment with business models. The majority of the organisations featured in this report have tried several ways to fund their operations before settling on at least one funding model which suits their particular niche. It is clear that not only is there no one model for funding digital journalism, but that it is normal for particular organisations to try different models over time. Rachel Oldroyd at The Bureau of Investigative Journalism reflects:

Our whole attitude to how we disseminate our work has changed quite a lot. Initially we set ourselves up as a production company, because we thought we could make money out of that. Then we went onto the ‘let’s be a traditional publisher’, and now we are just an investigative journalism unit, and that’s what we’re about.

Neither the advertising-funded sites nor those that rely on subscriptions or donations feel they have found a permanently sustainable model for funding digital news production. As the media environment continues to change, all are continually monitoring developments and assessing alternatives and potential additional initiatives. Advertising-funded sites face declining rates for display advertising bought and sold programmatically through ad exchanges, as well as intense competition from large technology companies that can offer cheap, precisely targeted, and effective advertising. Subscription-based sites know that attracting and retaining paying users is hard. Donor-supported sites are exposed to foundations and individual supporters losing interest. All are focused on diversifying their funding model to increase their chances of long-term survival and success.

A lot depends on what the definition of success is. The experience so far suggests that the digital news business is far from lucrative. Many legacy news media continue to lose money on their digital operations, even after 20 years of investment (Cornia et al. 2016). Even very high-profile US-based international digital-born news media sites with attractive audiences and considerable global reach, like BuzzFeed, the Huffington Post, Quartz, and Vice, continue to operate on a reach-first, profit-later model where continued expansion is frequently funded by investors more interested in long-term growth than in short-term sustainability. Despite its ambitious expansion and additional investment after the acquisition by AOL in 2011, the Huffington Post reportedly continued to miss Arianna Huffington’s optimistic revenue and profit projections as the digital media environment evolved (Cohan 2016).

Those contending to be small and sustainable are less pressured to pursue continued growth. This includes some privately held sites but of course in particular mission-driven organisations simply seeking to be ‘big enough’ to make a difference. Kerry-Anne Mendoza at The Canary in the UK is particularly direct:

We aren’t looking to be a Rupert Murdoch empire. What we really wanted to do was prove a test of concept effectively, and say “look we started with literally nothing”. So we set up a website. There is no external investment, no government grant, no anything, and [we are] able to get to a year later [and] people are quitting their full-time jobs, writers are earning decent incomes, we are pretty stable in terms of our readership. It is going up continuously and not down.

Other case organisations seem equally mission-focused, even if their editorial mission is less overtly political than that of The Canary. At El Español, María Peral says: ‘Many people at El Español left good posts at El Mundo, in my case for example, so I forget my old life and this is an adventure for me. I believe in this project because it’s a good project.’ This approach is very different from the growth-focused model of many high-profile US-based international digital-born news media organisations.

Distribution Strategies

Digital-born news media have historically been based around a website but increasingly have to deal with the move towards a more mobile and distributed environment where digital intermediaries like search engines and social media play an important role in distribution. Just as for legacy media, this changing environment comes with both opportunities and challenges. Search engines and social media first of all promise reach and the potential to convert a bigger audience into more loyal readers and, for those who seek them, paying subscribers or donors. But digital intermediaries also come with risks, as they influence what content people come across and where and how they do so, and as they represent competition for both attention and advertising.

The Role of the Website

For both advertising and subscription-based digital-born players, and particularly for those who aspire to be a regular destination and build a large and loyal audience, the website is still central. The website is critically important for sites like El Confidencial and the Huffington Post in terms of generating advertising revenues. For others, like Mediapart and Les Jours, it is important for signing up subscribers.

For most of the organisations covered, the website is still central to their distribution strategies as well as their funding models. But for some, especially non-profits based on foundation support, like The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Correctiv, their own website is actually secondary to other forms of distribution, including the websites and legacy channels of partner organisations. In both cases, their own website is seen more as an archive for stories, where readers can explore all of the work on a topic and come in sideways via, for example, search, and less as a destination for direct traffic. As Christian Humborg at Correctiv says, the website is not the ‘main window’, but a ‘container for articles’. ‘The key is to get out to the people the articles through the link.’

Several digital-born news media underline that they simply do not produce enough stories to become destination websites. (Similarly, very few try to offer a mobile app to compete for the limited number of apps people actually use on their smartphone – a space where the head-to-head competition with popular legacy brands seem too intense for most.) Correctiv, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, and Mediapart all say a large output is necessary for drawing users back to the site regularly. Rachel Oldroyd argues this would be a poor use of The Bureau of Investigative Journalism’s finite resources: ‘The energy and resource required to build an audience requires so many stories to be published a day that you end up using all our resource on that, as opposed to doing investigative journalism, which is why we feel there’s a gap.’ For Mediapart, the limited output, with seven to ten articles per day, is seen as a virtue in itself. François Bonnet say, ‘We’re not a free site caring about a maximum of clicks looking for audience. We don’t have ads, so we don’t have the logic of an audience. Our editorial logic is hierarchised quality and restraint on information.’

Some of the digital-born news media we cover also use their website for purposes other than distribution – especially engagement. Several have special subscriber sections on their sites (eg ‘Zone ñ’ on El Español, the supporters’ section at Correctiv). In Mediapart’s editorial concept, the subscriber/blogger section ‘Le Club’ both promotes discovery and also builds subscriber loyalty. François Bonnet says,

This community of readers share on social media, email, and you will find these in Google, which is how people find Mediapart. Le Club is the way in to us. People realise we are a media, and then subscribe. … Le Club also fulfils a function which is very Anglo-Saxon, which is op-eds, which we get a lot of pitches for.

The Huffington Post was the first to really demonstrate the potential of this model of a community of voluntary and unpaid blogging contributors, and it is still central to their site. In Spain, for example, El Huffington Post’s editor-in-chief Montserrat Domínguez argues that the site’s Spanish bloggers have reflected the voice of a disenchanted, educated public dealing with an economic crisis more accurately than much mainstream news:

With no jobs, this anger inside of the people … El Huffington Post gave the chance not only to the traditional voices, politicians, or intellectuals, but also to an array of people who wanted to express how bad they felt about the system, because the system was failing.

Distributed Discovery and Distributed Content

Increasingly, however, users are not coming direct to websites by bookmarking them or typing in the URL, but arriving via distributed discovery, including, most importantly, search (Google) and social media (especially Facebook) (Cornia et al. 2016, Newman et al. 2016). Some of these intermediaries also increasingly offer opportunities for distributed content, where not only discovery, but also consumption, takes place off-site. The most talked-about example is Facebook’s Instant Articles, where publishers’ content is hosted on Facebook’s site and loads within Facebook rather than offering a link to go to the publisher’s own site. Other examples include Snapchat Discover and Apple News, though it is unclear how important these are in Europe at this stage.

Different digital-born news media rely on intermediaries to different degrees. At El Español, about 21% of traffic is direct, and 28% is via organic search results – compared to 40% through social media. Laura Sanz explains how this is both good and potentially a longer-term risk that the site is working to manage:

Facebook is a good source of new users, but we need to try to engage readers to come from other sources. We select the stories that we post but it is dependent on the algorithm of Facebook who it will be shown to. So even though we have 180,000 fans on Facebook, if you go to our profile and you check the reach of a post, it doesn’t have more than 80,000, meaning that the algorithm is translating what it thinks will be best for each user. If they do change their algorithm, we’re lost. It’s in the user’s hand, but that’s our main focus.

Even partner-focused investigative organisations who see their websites as archival nevertheless get significant traffic and visibility from social media. Rachel Oldroyd at The Bureau of Investigative Journalism says,

Despite the fact that I said people don’t come to Bureau to read a piece of investigative journalism, we do have quite a good following on social media. Very good Facebook following for the quite niche areas that we cover, good Twitter following, good news list, subscribers list. So a lot of people do come to our content through that.

Very much like both private sector and public service legacy media (Cornia et al. 2016, Sehl et al. 2016), digital-born media seek to leverage intermediaries like search engines and social media to increase their reach, even as they sometimes also worry about losing control of their editorial identity, data on users, and parts of their funding model in a more distributed environment.

It is hard for both digital-born news media themselves and for outside observers to really understand what drives fluctuations in how much reach different intermediaries offer. A change to the Facebook NewsFeed algorithm in the summer of 2016 to prioritise ‘things posted by the friends you care about’ was anticipated to ‘cause reach and referral traffic to decline for some Pages’. Though the exact changes are opaque, the effects are felt by many. As Sebastian Esser, from Krautreporter, puts it:

At the moment we feel like we’re being punished by Facebook. Not us specifically. … We use Facebook as a means to pull people on our website and convert them into paying subscribers. And that doesn’t work as well any more, at the moment, because of the changing algorithm of Facebook. So in that way, we are really dependent on Facebook, even though I think that we don’t do the kind of content that usually is made for social media.

Sebastian Matthes from Huffington Post Deutschland talks about how they are working to simultaneously leverage the potential reach that platforms represent while also managing the platform risk that comes with being very dependent on a few sources of traffic:

I would try to say that in a positive way we are entering an era of big platforms now and you, as a media company, have to think about how you are going to service in this platform business. You cannot only survive long term on being dependant on Facebook, so you have to try to build your own platform.

Some are more sanguine about working with Facebook as a dominant platform. While Le Huffington Post wouldn’t test Instant Articles because of Le Monde’s decision not to, and the perceived lack of advertising revenue from it, El Confidencial were the first in Spain to test it, saying it has brought in more audience. Nacho Cardero, editor-in-chief, says, ‘It’s our problem for not knowing how to monetise the audience that we have. We’re not blaming Facebook and Google, it’s too easy. Later we can talk about the look and feel of Facebook, the revenue … but the more people who read us, the better.’ Stephen Hull, at Huffington Post UK, suggests the relationship is mutual rather than imbalanced: ‘I know from talking to Facebook that they’re very keen to make sure publishers can make those kinds of setups work, because there’s an acceptance that it’s a very symbiotic relationship that we’ve got.’

Off-Site Video

One of the major opportunities that platforms offer digital-born news media is the opportunity to offer video content via embedded players, especially off-site via video-sharing sites like YouTube and increasingly via video on social media like Facebook (including Facebook Live). Mediapart is now offering a live video on a monthly basis as an important ‘recruitment lever’ to encourage subscriptions. The newly unrolled strategy of a live weekly news programme is akin to broadcast media strategy and is closely intertwined with Facebook Live. For El Confidencial, video connects the media with the audience and creates engagement via social networks. All of the Huffington Post editions are investing heavily in video, with Sebastian Matthes in Germany noting, ‘Almost 40% of Huff Post readers in Germany said they’d like to have a lot of video content.’ The Canary is starting video offerings in the interest of growing its audience and also to increase monetisation options. Kerry-Anne Mendoza says,

YouTube doesn’t provide a fantastic bang for your buck while you are growing. It is great once you are reaching millions of people, so we have a relationship with an advertiser in the US, who is working on our High CPM video model.

It is not yet clear how much audience demand there really is for online video news, with many users still preferring text, finding video inconvenient and pre-roll advertising off-putting (Kalogeropoulos et al. 2016). But, like private sector legacy media, an increasing number of digital-born news media are chasing the potential revenues of video formats, where rates are much higher than for traditional display advertising.

A minority of the organisations we cover were not interested in investing in video – some were conscious of the cost of moving from text into video production and some were sceptical of the likely return on investments in online video news. As Rachel Oldroyd at The Bureau of Investigative Journalism puts it:

As the Internet and publishing on the Internet becomes so much more sophisticated, people realised that it’s not cheap at all to produce a three-minute film. People are going, ‘Oh, but you can do it on your iPhone.’ And then they start properly looking into it … And then they have two cameramen and they have the producer and they have an editor, and suddenly a piece of three-minute content is costing way more.

That decision to produce studio-quality output is a choice. Christian Humborg at Correctiv says, ‘As long as you stay in the YouTube world [instead of HDTV] you don’t need that much money, and I think you have to do it.’ In any case, expanding into video-based content needs new skills and attitudes; Daniel Drepper, senior reporter, says Correctiv is ‘making up for being built by print people’. ‘Most of the people we started with came either from online or print outlets … video engages people well. We still don’t have anyone who is a native video guy.’

For Raphaël Garrigos at the advertising-free Les Jours, video should only be used to move a story along, and is not the future of digital-born media. ‘There is always a tendency when you are in an industry that has troubles – you think that the next big technology will save you. It’s not like that. I don’t think there’s a miracle.’

Managing Platform Risk

By concentrating on search and social as drivers, news media risks becoming dependent on a few intermediaries for discovery. Like legacy media, digital-born news media are working to manage this in part by maintaining their own direct channels (website, email newsletters, in some cases mobile apps), in part by working with a variety of platforms, even if many of them are very small sources of traffic compared to Google and Facebook.

Stephen Hull, at Huffington Post UK, captures some of this dilemma:

You look at platforms like Snapchat to see where the value is. How do we win on that platform? The risk is that if it disappears you’ve got a team of people who are producing for it who then won’t have a role, and that’s not a good way to build teams. We look to find the middle ground between throwing yourselves all-in to these platforms, and doing nothing. We have to experiment. Running a modern media organisation is about taking a spread of strategic bets.

The situation can be more challenging for smaller players, who have fewer resources to invest in smaller social media platforms. Sebastian Esser from Krautreporter sums this up:

We’re not putting a lot of energy in to Twitter anymore because it’s less than 5% of our traffic. Which used to be more like 20%. And so everything now is Facebook and Facebook is not working at the moment so that’s a challenge.

Email is another way in which digital-born news media try to maintain direct channels to readers. Christian Humborg outlines Correctiv’s approach to maintaining a direct connection that does not rely on intermediaries. ‘Number one, we get people to our website. The next step is that they give us their email address, because it is the only instrument where I can still reach people electronically without any intermediary who can change the algorithm.’ Marie-Hélène Smiejan at Mediapart agrees. ‘Readers have to come to us, and the only way to maintain a permanent connection with them is via email.’

It was not clear for several interviewees how effective off-site distribution would be as a means of generating money. A large share of the advertising revenue from platform distribution often goes to the platform, and news media with a subscription model noted that Facebook Instant Articles in particular was not yet geared towards this. As Sebastian Esser from Krautreporter notes, ‘We want people to be just one click away from being converted and that doesn’t work well on Facebook yet. I think they’re working on something.’

In general, the long-term economics of off-site distribution are uncertain: opportunities can be seen, but not yet the shape of sustainable revenue streams. Jack Riley, of Huffington Post UK, says,

Everyone in the industry is still figuring out what the valuation is of all the engagement that happens outside your site – that we’re all really happy to have because it’s reaching lots of people and engaging them in new ways you couldn’t necessarily do yourselves.

Editorial Priorities

The funding models and distribution strategies pursued by different digital-born news media are ultimately tied in with their editorial priorities. As noted at the outset, most of the cases we cover here are committed to forms of professional journalism that are broadly the same as many legacy media – some may have a clear partisan position, but generally, all see themselves as offering news and focus in large part on public affairs.

While they have organisational imperatives – whether for-profit or non-profit, they have to bring in money to sustain themselves – most of the cases we cover are highly mission driven with strong editorial priorities. This is perhaps particularly clear in the case of organisations like Correctiv and The Bureau of Investigative Journalism: non-profits built primarily to produce and distribute investigative journalism. But other organisations too have a clear commitment to a journalistic mission – in their different ways, Mediapart and Les Jours in France, and El Confidencial and El Español in Spain are founded by journalists who want to do distinctive and high-quality journalism in countries where newspapers in particular have had to cut their editorial investment in recent years. While one of our Huffington Post interviewees rather bluntly said, ‘We don’t do things that don’t really make money for us’, the Huffington Post still has a historical commitment as a liberal and progressive online news site (the current slogan is ‘Inform. Inspire. Entertain. Empower.’) and invests significant resources in editorial content.

The Competitive Field for Digital-Born News Media

The digital-born news media we cover have entered a very competitive market, both in terms of news audiences’ attention and in terms of advertising, subscription, and donations. In terms of new audiences specifically, the main competitors are legacy media, web 1.0 portals and content sites, and other digital-born news media, whether domestic or international. In terms of attention and advertising more broadly, the competitive field is much wider. As Sebastian Matthes, of Huffington Post Deutschland, observes: ‘[E]verything you can do in the Internet is a competitor now, because people spend time on Snapchat, people spend time on Facebook, doing whatever. So we have to compete against all these different other sources of fun and entertainment.’

El Confidencial states that there is a new actor every week in Spain. Nacho Cardero says, ‘It’s crazy to think that anyone can launch their own digital media, be read and find funding.’ And despite El Huffington Post’s ‘concern’ about legacy media, the competition is ‘energising’. Montserrat Domínguez says, ‘A lot of pure players are run by older-style journalists, who have run out of work or have decided to start a new adventure. There’s a lot of competition that we didn’t have when we started, which is energising, because we have to learn, and change quicker, if we see that is not working for us.’ María Peral at El Español, who worked for El Mundo for 15 years, recognises the challenges of changing a mindset: ‘The big problem in El País or ABC is how to lift the paper, the press, and change your mind, your journalists, everything to only in the digital. The advertising stays mainly in the paper.’

Paul Ackermann, editor-in-chief of Le Huffington Post, reflects that some digital newcomers in France based on US models have done less well. For example, Mashable launched with France 24 and Business Insider launched with Prisma (a German company, and the second largest magazine publisher in France):

Huffington Post launched big in France with Le Monde. They believed in it. We were eight at the beginning; there are 30 of us now. They never said “stop” or “let’s wait to make more money”. It’s, like, “go, go, go, develop, develop, develop”. In early 2012, we competed with the pure players – Rue89, Slate, etc. Today, we’re really out of the pure player category; no other pure player does even half the traffic that we do. We’re in the category of the big French media, and Libération is the closest to us, although it’s hard to call a newspaper with a newsroom of a hundred people a competitor.

Distinctiveness and Focus

All the digital-born organisations aim to develop a distinctive voice to stand out in the increasingly intense competition for attention. Nacho Cardero emphasises the importance of quality at El Confidencial and believes in a Darwinistic model of competition, where the best journalism will survive. ‘There are many inefficiencies in this apprenticeship period on the Internet,’ he says, ‘confusing quality journalism with another type of journalism which does not have the same principles or standards.’

How they approach this differs. All aim to be different, some through in-depth coverage of a few select areas, but others more through the development of a distinct tone across a wide array of topics and through bringing in distinct voices not normally part of other outlets. These different editorial priorities, some narrow, others broader, are at least in part tied in with different funding models. Advertising-funded sites need a bigger audience, whereas subscription- and donation-funded sites need to stand out from what is available for free.

Almost half of the cases covered here aim to stand out through their commitment to in-depth journalism and investigative reporting, often of topics they feel other media do not pursue enough. In France, François Bonnet says that Mediapart is founded on its commitment to political and economic investigation. ‘Investigative journalism had been abandoned in France for economic, political reasons,’ he says. Les Jours has similar ambitions and believes that the reliance on subscriptions rather than advertising will help them realise it. Raphaël Garrigos explains: ‘In France, for example, there are never any investigations on the cosmetics industry – these are the things we’d like to test.’

Similarly, in Spain, El Confidencial launched with a particular focus on business media, which Nacho Cardero calls a formula he would repeat again had he to launch today:

We grew because we were one of the first to specialise in economics. We would do the same today; there are so many competitors, and you have to specialise. … El Confidencial is about candid journalism – we’re fundamentally centred in investigative journalism – we are known for investigation, economy, politics.

He adds that people ask him how much they paid to publish the Panama Papers. ‘You don’t know which names are in those papers. For industry papers like El País and El Mundo, that could be a problem. We’ll publish it. We don’t care.’ Peral echoes this sentiment at El Español: ‘We cover investigation, especially corruption, the judicial process and business.’

Correctiv and The Bureau of Investigative Journalism are both highly focused on investigative reporting, and see themselves as specialists rather than general news sites. As Rachel Oldroyd at the Bureau says, ‘All of our work is big, long, investigative journalist research.’ Daniel Drepper at Correctiv highlights the difference between a breaking news site and a team of investigative reporters ‘[if it’s a choice to] be the first or be the definitive, I think the definitive is definitely important for us’.

Even the biggest of the above players and those most strongly influenced by their founders’ long experience in legacy media shy away from replicating the bundled model of newspapers. No one wants to offer a little bit of everything for everyone. There is a mix, but the mix is more focused. None of the cases studied currently have significant sports coverage, for example.

François Bonnet at Mediapart describes their particular take on generalist (but not fully comprehensive) online news:

What we cover has to have a real extra value. We specialise in politics, intellectual debate, investigations on the economic world, whilst still being generalist. We have developed our international coverage, because there was a real thirst for that. We do literature, debate of ideas, but only exceptionally performance art or theatre.

He also notes that Mediapart’s editorial line is defined by its rejection of agency news-style stories:

Shimon Peres died this morning [the day of the interview], but we won’t provide any added value to this news – our readers don’t come to us to read about his death. However, we do cover the Israel–Palestine conflict in detail and regularly. We need to provide readers that extra added value.

But a significant number of sites, most importantly those that are wholly or in part advertising funded, still cover a much broader range of topics. Huffington Post UK, El Huffington Post, Le Huffington Post, and El Español have invested in lifestyle journalism and a wider spread of women’s issues. Jack Riley, commercial and audience development manager at Huffington Post UK, reports, ‘We’ve gone from being about 50/50 on gender split to having a slight female bias now, which we’re pleased with.’ Laura Sanz at El Español similarly says, ‘August was 52.2%, the first month that female was a higher rate than male.’ María Peral, also at El Español, explains, ‘El Español is unique because it’s a media where women have power. Our CEO is a woman, 50% of the senior editorial team, four in the finance and marketing team. It is amazing.’

This does not mean, however, that they have given up on the idea of being different. They simply try to achieve this through tone and choice of topics rather than through a narrower, more focused editorial agenda. At El Huffington Post, this is about having a young tone, a different language and covering taboo topics. Montserrat Domínguez says the media has

broken prejudices about what content goes into a news site, which reflects society and changes. … We have put politics, economics, and trends, personal growth, mindfulness, and celebrities together on the same page, with no complexes. It’s not our mission to follow politicians, but what the people say, report it. … Sex, gender, things that you never have read about in a traditional newspaper [are] here. We’re having this great debate right now about surrogate motherhood.

Likewise, The Canary was set up to broaden the range of voices heard in British media; their founders came from the world of new media blogging, and it ‘focuses on news, ideas, and key developments that impact democracy, equality and fairness’ (The Canary 2016). Kerry-Anne Mendoza is particularly proud of their ability to offer work to non-traditional journalists, resulting in a different take on the news than established outlets, for which The Canary can be seen as complementary: