Executive Summary

This report looks at how news organisations are creating innovative editorial formats and seeking commercial opportunities ‘beyond the article’. The report and analysis are based primarily on case studies discussed in interviews conducted between December 2016 and January 2017 with start-up founders, senior editorial leaders, technology directors and commercial executives at news organisations in the United States, the United Kingdom, Finland, Spain, Turkey, and the Philippines.

We have found:

- All of the cases involve some form of distributed content, either the well-known process of spreading content through social networks or increasingly via messaging platforms, apps, and emerging virtual reality stores.

- The news organisations are moving beyond using distributed strategies simply to achieve scale. The editorial priorities included trying to build a more direct relationship with their audience, trying to increase engagement, or trying to reach a specific audience – in the case of Helsingin Sanomat a youth audience.

- Display advertising is playing less of a role in monetising these distributed audiences. The news organisations in this report are utilising a number of commercial strategies for these projects including sponsored content, native advertising, commercial partnerships, and the sale of services.

- While the virtual reality projects involved a great deal of resources – the resources only available to news organisations with a global reach such as the Guardian or the New York Times – most of the projects do not. One of our case studies, 140journos, has a full-time staff of only 10.

And the case studies show how news organisations have developed product management processes not only to increase the pace of innovation but also to try to increase the chance of commercial success.

Introduction

‘The future of news is not an article’, Alexis Lloyd wrote in 2015. The then creative director of the New York Times R&D Lab continued: ‘News has historically been represented (and read) as a series of articles that report on events as they occur because it was the only way to publish news’. He argued that journalists and news organisations needed to let go of old, inherited constraints and rethink what news might look like in a thoroughly digital media environment. 1 In this report, I examine a range of examples of news organisations thinking ‘beyond the article’ in terms of both the content they produce and the commercial revenue that supports their journalism. The focus is on both editorial and commercial innovation, because the current pressures on existing business models for news mean that the two need to go hand in hand for journalism to find a way forward.

The report is intended to provide a snapshot of some important examples of how different news organisations are developing news ‘beyond the article’ through an embrace of distributed publishing, through the use of messaging apps and chatbots, and through the development of new forms of visual journalism including mobile-first video and virtual reality. These three areas are examples of current experiments underway in news, and all the experiments examined here are analysed against the backdrop of already well-documented structural changes in the media: a rapid shift towards a more digital, mobile, and platform-dominated environment (Newman et al. 2016) combined with significant pressures on existing business models for digital news based around display advertising (Cornia et al. 2016).

The cases examined include a few of the usual suspects in discussions around innovation in news, namely high-profile English-language organisations like the Guardian, the New York Times, and Quartz. But because news organisations’ resources and market opportunities vary greatly and most operate under very different conditions from those found at the New York Times, I also look at interesting examples from elsewhere, including digital-born start-ups like 140journos from Turkey and Rappler from the Philippines as well as legacy media like El País from Spain and the Helsingin Sanomat from Finland. The cases and examples are not exhaustive and not necessarily representative of the industry as a whole, but they are indicative of some of the experimentation underway in journalism and illustrate how news organisations are trying to think beyond the article.

In the first part of the report, I examine 140journos and Rappler as examples of aggressively distributed publishing and the opportunities and challenges that come with it. In the second part, I discuss how Rappler, Quartz, and the Helsingin Sanomat have worked with messaging apps and chatbots to expand and maintain a direct relationship with their audience and grow new commercial opportunities. In the third part, I look at examples of new forms of visual journalism from the New York Times, El País, and the Guardian, all three ‘old’ newspapers that have invested in video and virtual reality in recent years. The concluding section identifies some common features of how these different news organisations are working to shed inherited constraints and thinking about the practice and business of journalism beyond the article.

The Full Embrace of Distributed Publishing

Publishers are increasingly embracing distributed publishing and are reliant on platforms including search engines, social media, and messaging apps for audience reach (Newman 2017). Many are trying to replicate the success of digital-born publishers, most notably BuzzFeed, which publishes to 30 different platforms in 11 countries and in seven different languages, with an estimated 80% of reach from platforms rather than its own website (Liscio 2016). This distributed strategy has helped turn BuzzFeed into a 5 billion page view per month behemoth (Moses 2016).

Publishers are using these platforms for their own strategic goals while also being locked in competition with them, especially Facebook, not only for audience attention but also for advertising revenue. 2016 saw a marked shift in advertising. In English-language markets, Google and Facebook captured most of the digital advertising growth (Benes 2016).

BuzzFeed and Al Jazeera’s experiment in distributed publishing AJ+ are just two examples of publishers pushing the boundaries of a highly distributed strategy. Here we look at two others that are pursuing highly distributed content strategies, in both distributing and in gathering information: 140journos in Turkey and Rappler in the Philippines. Both have used social media to fuel incredible growth and to crowdsource information, but are now finding limits to that strategy. For 140journos, that limit has been revenue, while Rappler has had to adjust its strategy as social media users in the Philippines shifted quickly from Twitter to Facebook over the last year.

140journos: Seeking Sustainability in a Repressive Media Environment

140journos is a citizen journalism project in Turkey, and its radically distributed social media approach, operating on as many as 15 platforms, allowed it to grow rapidly. But in a country where the traditional media engage in high levels of self-censorship and face increasing pressure from the government, 140journos has not been able to secure investment. Instead, it funded its initial phase of growth through revenue from a creative and events agency, the Institute of Creative Minds. In 2017, it will launch a range of revenue experiments in hopes of supporting a new phase of growth for 140journos.

The project took its inspiration from coverage by a single journalist in 2011 in the wake of a deadly airstrike by the Turkish military on a village in a Kurdish area along the Turkey–Syria border. Traditional Turkish media often engage in self-censorship around politically sensitive topics, and few are more sensitive than coverage of the Kurdish conflict in the country. However, in this instance, a single journalist, Serdar Akinan, who wrote for the Turkish evening newspaper Aksam, broke the media blackout. He travelled to the area, and using only Twitter and Instagram, he posted pictures and snippets of interviews with grieving families burying their dead (Zuckerman 2014).

It was a pivotal moment for then college student Engin Önder and two friends. They saw an opportunity to use Twitter and other social media platforms to break pervasive self-censorship in the media. Not long after Akinan’s breakthrough coverage, Önder live-tweeted a controversial trial. The judge threw all of the traditional media out of the court, thinking that it would stop the posts, but because Önder and his friends weren’t members of the media, the tweets continued. 140journos was born, the name a reference to the 140-character limit on Twitter (Lichterman 2014).

‘We were correspondents, practising the most basic and core level of journalism even though we were not trained or wanted to be journalists,’ Önder said. 2 The next year, as the protests in Gezi Park erupted, he noted that ‘we were on the ground, creating a vibe on social media to follow current events and report from the ground with our friends, pals, networks’. They collected, verified, and amplified posts, pictures, and video shared on social media and sent directly to them.

Önder said that social media allowed them to more easily gain reach, recognition, and rapid circulation of their work. They are currently active on 15 different social media platforms and have adapted their publishing strategies to the unique nature of each platform: ‘Twitter is more of a real-time content whereas WhatsApp is a chat platform.’ They use WhatsApp to communicate with their contributors, who number in the hundreds, and to create a dialogue with their audiences.

‘We even experimented with Tinder by creating various profiles with fake, Photoshopped stock images to deliver our news to a group of people that never interact with what’s going on in Turkey,’ he added.

To stand out in the crowded, noisy social media space, they have cultivated close relationships with the platforms. They will soon get a broadcaster badge from Periscope, which will increase promotion of their videos, and they have a deal with Eksi Sozluk, Turkey’s biggest social media platform, to be a content sponsor on the service. They are constantly experimenting with various platforms not only to keep pace with rapid changes in user behaviour but also to develop contingency plans in case the government intensifies its censorship efforts.

While their highly distributed strategy has helped them scale and circumvent censorship, it has not been without its challenges. It takes a lot of work to adapt their content to so many platforms, and with the end of the street protests and the post-coup crackdown, they have fewer contributors who are providing first person reporting from the streets. And in line with social media habits around the world, Turkish users are switching from open networks like Twitter and Facebook to more closed, private messaging apps.

The biggest challenge 140journos faces is financial, Önder said, adding: ‘Making money is not easy. Appealing to investors for a political news site is almost impossible.’ So far they have earned the bulk of the money from the Institute of Creative Minds. However, in 2017, they plan to launch new content and revenue initiatives, which include:

New niche verticals

- A membership scheme for their most loyal readers.

- A subscription service that will allow for a degree of personalisation for content in their key verticals.

- Sales of some of their generic images and videos to stock content sites.

- Direct sales of high-quality images and videos.

- Sales of the rights of some of their best documentaries.

- A premium news service in English to professional journalists covering Turkey. 3

The revenue strategy represents both a greater emphasis on reader revenue and also segmentation of their audience into public and professional audiences. It borrows from a number of reader revenue strategies while adding in some new innovative approaches.

Rappler: Responding to Rapid Shifts in Consumer Social Media Behaviour

Rappler is a digital news service in the Philippines. Like 140journos, Rappler began its life on social media, as a Facebook page, in 2011 (Posetti 2015). Move.PH is now the citizen journalism and civic project unit for Rappler. Social media helped the site grow rapidly, and within six months of its launch, the site was receiving between 2 and 3 million page views. Rappler CEO and executive editor Maria Ressa told Harvard’s Nieman Lab in 2012: ‘In Rappler’s first month, we hit the traffic it took the largest Philippine news group a decade to reach. That’s the power of social media.’ 4

From its launch, its founders knew that to maintain its editorial independence Rappler must have a sound business model, Ressa said. They have done this ‘under the banner of #BrandRap, [in which] Rappler provides client brands a custom combination of content creation, native advertising, social media engagement, crowdsourcing, and big data’ (Ferraz 2015).

They have four public service crowdsourcing projects under the auspices of Move.PH (Posetti 2015), and one of the primary sources of funding has been international aid agencies and governmental agencies in the Philippines, depending on the project. But the company is exploring new revenue streams and forms of support to aid ongoing development, including crowdfunding and the possible sale of the data collected by the platforms.

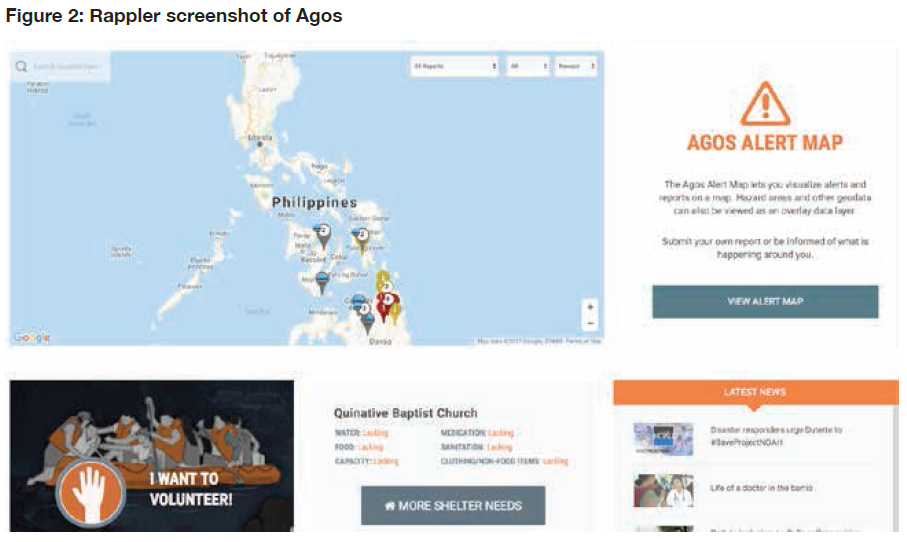

One of the projects is called Agos, which crowdsources disaster response. ‘During disasters, one of the things that people look for is how we can help,’ said Gemma Bagayaua Mendoza, who heads up Research and Content Strategy at Rappler. 5

Project Agos launched in September 2013. ‘Ironically, we started a couple of months before Typhoon Yolanda. Before Yolanda, it was difficult to get government buy-in’, Mendoza said, but after the typhoon, there was a realisation by the government that it needed to involve all stakeholders.

The Agos platform analyses messages via social media or a special SMS number to determine areas that need the most help after a natural disaster and to connect people with help. The system not only collects information but also gives officials a way to verify and validate reports. The service has been activated for floods, typhoons and earthquakes. 6

In addition to the Agos disaster project, Rappler has also launched initiatives to report bribes and corruption, called NotOnMyWatch, or simply #NOMY. The service allows Filipinos to report bribes, other forms of corruption and slow response, but also examples of good government service. All of the information is aggregated visually on a page on the Rappler site. 7

Initially, Rappler relied on Twitter for these crowdsourcing projects and created a unique set of hashtags such as #floodPH and #typhoonPH to easily aggregate disaster reports for Agos, but in the past year Twitter use in the Philippines has declined, Mendoza said.

They haven’t studied why Twitter has declined, she said, but she attributes it to the nature of Twitter and its competitor Facebook as well as Filipino culture. ‘Twitter is mostly for consumption of information, but Facebook provides a bit more in-depth experience that loops into family and networks,’ she said, adding that almost every Filipino has a family member who lives abroad so Facebook helps them stay in touch.

Facebook has also increased its use in the Philippines by subsidising data to use its platform. The vast majority of Filipino mobile users have prepaid rather than contract plans, and since 2013, Facebook has offered programs in the country to provide free data service for users first for its mobile site and later for its app (Consunji 2013). This has helped to make Facebook the most pervasive social network in the country. ‘Even my mom uses it,’ Mendoza said. Consultancy We are Social estimated that there are 54 million Facebook users in the country, more than half of the population. 8

Rappler has had to modify its strategy as Filipino social media tastes have changed, and it highlights one of the challenges of a distributed strategy: reliance on one platform can leave a project or even entire news service vulnerable if the team isn’t nimble enough to keep pace with changing consumer habits or, in the case of Facebook, changes to its algorithm or strategy. Rappler’s in-house development team has allowed the site to adapt as users have shifted to Facebook and messaging apps.

To pay for this public service project, Rappler has partnered with a wide range of academic, civic, governmental and non-governmental organisations including ‘the Climate Change Commission, the Office of Civil Defense, the United Nations Development Program, the Department of Social Welfare and Development, and other partners from the academe, civil society, the online community, and the private sector’. 9

Governmental and international support for the project has provided a relatively stable foundation for their crowdsourcing projects. They are also considering white labelling the technology – allowing other publishers to use their technology but under the other publishers’ brand – as an additional revenue stream, Mendoza said.

They believe that the data they have collected could be valuable to the private sector, and they are considering ways that they might be able to sell that data, according to Nam Le, chief technology officer of Rappler. ‘We ultimately want to make sure that these platforms are free to our community,’ he said. 10

News as Conversation: Apps and Chatbots

Increasingly, mobile has become the primary digital channel for people to access information, to interact on social media, and to communicate using messaging platforms (Barot and Oren 2016; Newman et al. 2016). And as Önder of 140journos said, audiences are shifting from open social sharing platforms to more closed messaging platforms. Usage of the big four messaging platforms – WhatsApp, WeChat, Vibr and Facebook Messenger – overtook the big four social media platforms – Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat – in terms of monthly active users in early in 2015, according to Business Insider’s intelligence unit (BI Intelligence 2016).

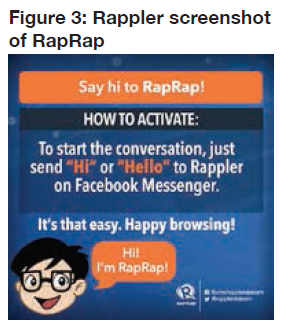

To remain relevant to audiences increasingly using messaging but also to respond to what they see as limits of Facebook’s algorithms and newsfeed, Rappler has developed a Facebook chatbot to help users discover more of their content, and as their userbase has shifted from Twitter to Facebook, they are also developing chatbots to feed information into their crowdsourcing projects.

For Helsingin Sanomat’s Nyt youth-oriented section, they initially experimented with distributing their content and engaging their audience through WhatsApp, which enjoys 80% usage amongst their target demographic. They launched the experiment to try to deal with limits they were seeing in reaching their audiences through traditional social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook. After quickly reaching the limits of their WhatsApp efforts, they decided to develop their own chat-based app.

In addition to developing chat-based apps to try to capture users who are spending increasing amounts of time with messaging platforms, publishers are also trying to take advantage of another mobile trend, notifications, to build engagement with users (Newman 2016). And as the amount of consumer usage of notifications has tripled in most countries over the past three years, publishers like Quartz in our case studies have pivoted their mobile strategy in an attempt to get into this notification stream (Newman 2016).

The development of conversational formats are forcing news organisations to be as creative commercially as they are editorially to create ad formats and experiences that feel native to conversational formats. With advertisers increasingly wanting to reach mobile audiences, these messaging and app strategies hold opportunities for groups looking for revenue growth.

Rappler: Enhancing Facebook Discovery and Crowdsourcing with Chatbots

To address the shift in use from Twitter to Facebook and also to encourage their users to explore their content more deeply, Rappler recently launched a Facebook chatbot. The chatbot is a simple conversational application that allows users to ask basic questions or enter keywords to explore information on the Rappler site. And they are also experimenting with a chatbot for their crowdsourced corruption reporting programme, according to Gemma Bagayaua Mendoza, who heads up Research and Content Strategy at Rappler. 11

For Rappler, the primary motivation to create a Facebook bot was to address what they saw as limitations in reaching their readers on the dominant social media platform. Mendoza said:

People are really seeing a lop-sided view of what we are serving our public, and that has an impact on the quality of discourse. In the Philippines as in the United States, the echo chambers are really out there, and they are affecting how people respond to situations in current events. We would like to be able to have direct access to people so they see the whole picture.

Not only did they want to highlight more content to users than Facebook’s algorithms were surfacing, they also wanted to be able to communicate their editorial voice and priorities to their readers. The news feed is flat, she said.

You don’t get a sense of what are the top five stories. Everything is in the same order. One of the consequences of that is that people don’t see the significance that we give to different types of news. They don’t see differences between opinion pieces and in-depth analysis.

The first round of development was relatively quick and easy. They dedicated two developers to work on the RapRap bot. ‘With the big push from Facebook to get their messaging technology to developers, the effort was fairly low. The challenge is figuring out how to build an interface that will allow our users to know how to interact with the bot,’ said chief technology officer Nam Le. 12

When launched, users could send brief messages to the bot – like ‘Top Stories’ to get the headlines or a keyword to get all of the stories on a subject. 13 They are now working on how to make the bot ‘a little more human’, he said, adding that they hope to get to the point where a user would be able to ask the bot a question like, ‘What is happening in Mindanao?’ And the bot would return a list of articles or things going on in that area.

They are also adapting the bot for their crowdsourcing projects such as #NOMY, the good governance and corruption reporting project. However, at the moment, the bot isn’t sophisticated enough to differentiate between people requesting and people submitting reports so they are using it simply for reporting. The bot walks users through questions that are similar to filling in a webform, he said. ‘It’s leveraging the whole free internet access. With Facebook Messenger, they are starting to have a dialogue with the bot,’ he said.

They routinely conduct training roadshows to build awareness of the project but also to train users on how best to submit information for their crowdsourcing projects, but as Facebook chat has become ubiquitous they hope that training will be relatively easy or even unnecessary.

In terms of revenue, if the bot gets Rappler readers to read more stories, that will increase their advertising revenue. They also get some support for their chatbot development for their crowdsourcing projects through grants, and they have received in-kind support from private sector companies. But the service is still new, and ‘our sales team is looking into how to leverage the eco-system’, Mendoza said.

For their crowdsourcing projects, Le said they are also exploring crowd-funding for additional development support.

Quartz Targets the Mobile Notification Stream

Quartz is a rapidly growing business-focused digital news outlet owned by Atlantic Media Co. At a seminar at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Quartz reporter Akshat Rathi said the service has three guiding principles: ‘provide global business news, respect readers’ time and go where the readers are’ (Turtola 2016).

Quartz launched in 2012 with the belief that ‘mobile is king’. Despite this mobile-first focus, it initially did not have a mobile app, instead relying on a responsive site without a home page (Turtola 2016). Their initial thinking in deciding on a ‘mobile web optimised experience’ over an app was that, with ‘most news apps, people might install them. You might get a decent user base, but then [app usage] tail[s] off really quickly. They forget that they have [the app]’, said Adam Pasick, the push news editor for Quartz. 14

The rise of notifications changed their thinking. ‘Notifications gave us a way to get into people’s lockscreen and remind them that we were there,’ he added. It was part of their guiding principle to go where readers are.

To get into the notification stream, the Quartz development team toyed with several ideas, including everything from a mobile version of the website to very stripped down mobile experiences, ‘maybe just notifications and nothing else’. However, ‘[t]hat felt a little too bare boned’, Pasick said. Playing in what Pasick called the middle ground between the two extremes of a full-blown traditional app and nothing but notifications, the team settled on an app with a conversational interface.

The original inspiration came from non-news apps including Lark, Pasick said. Lark is a fitness app, which conversationally guides users to their fitness goals (Kleinman 2015).

They wanted the experience to feel as close as possible to a messaging app. In his interview Pasick said: ‘The amount of time that people are spending with messaging apps is starting to eclipse social media apps themselves’, adding that they wanted to make it feel like ‘you were having a conversation with … the Quartz newsroom’:

We are not trying to be a comprehensive news source that tries to tell you everything in the world you need to know about business, tech or politics. We’re providing a very slim, curated view of things that we find interesting. … We write plenty of stuff that’s 10,000 words – a deep-dive into a very narrow obsession. This is at the other end of the continuum.

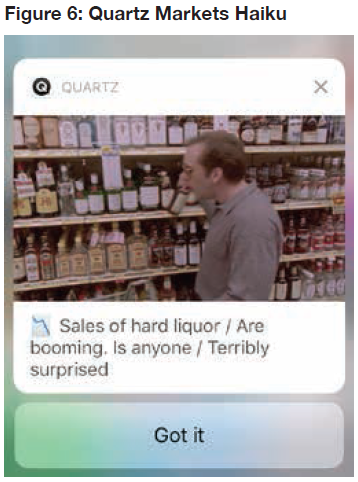

The app launched in February 2016 with a limited amount of personalisation. Users can choose which of four categories of notifications they want to receive: basic news updates, important and interesting news, ‘Really, really big news’, and the Markets Haiku.

The ‘Really, really big news’ is the only update where the app will buzz your phone, and Pasick says that they have only used it only three times. ‘We call that our apocalypse option’, he said. They used it for the results of the 2016 presidential elections, when Prince died, and for one of the major terrorist attacks last year.

The Markets Haiku – a poetic, often cryptic summary of stock market activity in the 5-7-5 syllable common English haiku format – predates the app, Pasick said. They developed it for the Facebook Notify app, ‘which is no longer with us’. He adds: ‘Most market reports are just the most boring, uninteresting things in the world. I think it is people trying to assign a narrative to random noise half the time.’ But stock market results are inherently interesting to a business site so they tried to come up with a creative approach to what is otherwise is relatively undifferentiated content. For instance, their Markets Haiku for the day of Donald Trump’s inauguration quoted words from his address. ‘“Sad”, “rusted”, “carnage” / Trump’s words for America / Should we all buy gold?’

The tone of the updates is conversational and has developed over time, Pasick said, adding, ‘We wanted the voice to be the voice we used when we were talking to each other on Slack’ (the enterprise internal messaging and collaboration platform). It is intended to be an informal but news-obsessed voice that also avoids ‘dry, conventional news language’. It is relatively easy to keep the tone consistent because the team updating the app is quite small, ‘about four people, spending all or part of their time on it, scattered across a bunch of time zones’.

The app mechanics are relatively simple. The notification arrives, and once users click into the app, they are given the option to read the full story, click on a usually emoji-filled icon that allows them to get more short, conversational updates on that story, or click ‘Anything Else’ to get the next story summary.

The team has begun to delve into the data about how users are using this simple story navigation, but the team is not releasing any details about it. Pasick was willing to provide some top-line figures about user engagement: ‘Our core users, people who use the app everyday, use it 2 minutes at a time, once or twice a day. That is really a small snack size as far as reading the news goes.’

Quartz launched an Android version of the app in December so continued investment implies that the app is meeting the goals of the company. To monetise the app, Quartz has developed novel ad formats that fit into the infinite scroll. Similar to the in-stream ad format on their initial responsive site, visual ads flow into the update stream of the app. The ad units appear as the user opens the app.

Quartz creative director Brian Dell said that ultimately their goal is not to ‘[match] commercial to editorial’ but rather to deliver ‘a great Quartz experience’. ‘So instead of matching editorial design, we work to match our user’s context, and build the best brand experiences for that in a Quartzy way,’ Dell said. For the app, he said that users are ‘primed for interaction and play’. They try to create brand experiences that match that context.

Helsingin Sanomat: Chat as a Way to Reach Youth Audiences

Nyt is the youth-oriented section of Helsingin Sanomat, the largest newspaper in Finland. It is intended to be a ‘gateway drug’ to get youth interested in the paper, says Jussi Pullinen, a news editor with the paper.

Before 2013, their digital efforts were strongly grounded in print. They would post print stories online and share them on social media. In 2013, they decided to relaunch digitally, unveiling a new website, and like many news organisations, they relied heavily on social media to build their reach. But they soon noticed they had plateaued with their initial social media-led approach to grow reach in their target audience of 15- to 26-year-olds, especially the younger members of their audience. ‘If you want to reach young masses, Facebook is increasingly not the way, if we’re talking about teens,’ Pullinen said. 15

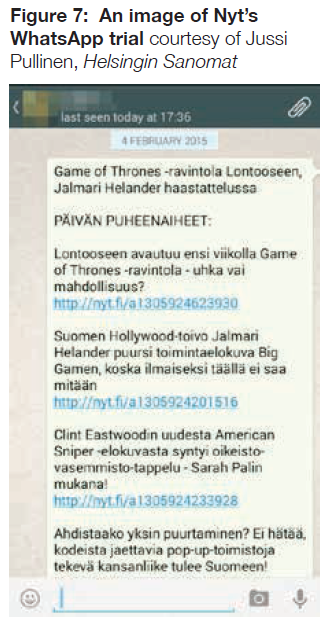

They did see a way to reach their young audience via messaging platform WhatsApp. In Finland, WhatsApp is used by almost 80% of youth and they spend large amounts of time using the messaging app. Nyt launched a newsletter on WhatsApp in the autumn of 2014. ‘There are no developer tools on WhatsApp. We just did it by brute force’, Pullinen added. They started simply, publishing a few top stories, a few headlines, and a joke. Their initial launch was not marketed heavily. They simply published the number and expected to get a few hundred ‘early adopters’, but within a week, they had 3,000 users and shortly thereafter, they had to cap the number of users at 5,000 (Pullinen 2016).

‘People liked it. We got good feedback,’ he said in his interview with me in 2016. Their young readers sent them messages as well as audio and video files. And they asked the Nyt team questions. The team responded, and they asked their WhatsApp users what they should add and what they should drop.

In a post on Medium, he attributed their success to an editorial voice that resonated with their young audience, the short digest format, and the local focus: ‘People who were from the Helsinki region really liked getting tips on new restaurants or bars or info on events on the town via chat’, rather than having to look it up.

But due to the limitations of WhatsApp, they found the project to be unsustainable. WhatsApp limits a distribution list to 250 users so they had to manage almost 20 lists manually, adding and removing people. ‘It became a manual labour hell pretty quickly’, he said to me, adding, ‘It felt a bit rickety.’ They were concerned that WhatsApp might decide that they were spamming users and cut them off.

And there wasn’t a clear business model. They weren’t able to get users to click through to the Nyt site ‘[s]o driving traffic was not going to be a viable business model’ (Pullinen 2016). And they didn’t put advertising on their updates on WhatsApp for fear of breaching the terms of use on the platform. However, their young audience’s enthusiastic uptake of the WhatsApp experiment proved to Pullinen that the conversational format resonated with them: ‘We realised that we were outgrowing the WhatsApp platform, but maybe we should build [an app] around the same content.’

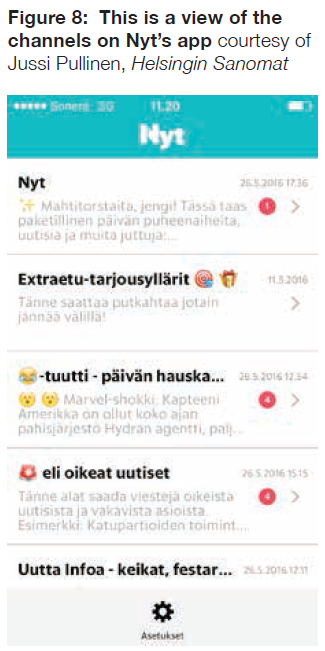

They worked with an external firm and were able to build the app in three months. It not only mirrored the conversational format of WhatsApp but with the added advantage of having editoral tools was much easier to manage.

Adoption was rapid, and they quickly got between 20,000 and 30,000 downloads, which equates to about 10–15% of users who access the Nyt website weekly. The app starts with a pre-loaded greeting and then loads a list of channels including news, music and humour, like a chat service.

Just as they had used WhatsApp to get content and input from their audiences, they have used their own app to do social reporting. They did a story about the decrease in sexual activity by younger people. They asked their young audience if they thought this was true. ‘We got a huge amount of replies. We used pseudonyms and got really deep stuff, really good reporting’, Pullinen said in my interview.

Despite that success, they have not had as high an engagement rate with their app as they had on WhatsApp. With the app, a third of users come through notifications. ‘With WhatsApp everyone came through notifications’, he said. Another third of users of the app open it once or twice a day to check the channels that they are interested in.

Helsingin Sanomat also see a challenge in that they now feel they are in competition with WhatsApp. ‘Our core audience is on WhatsApp all the time. When you have a separate app, you have a threshold there’, Pullinen said.

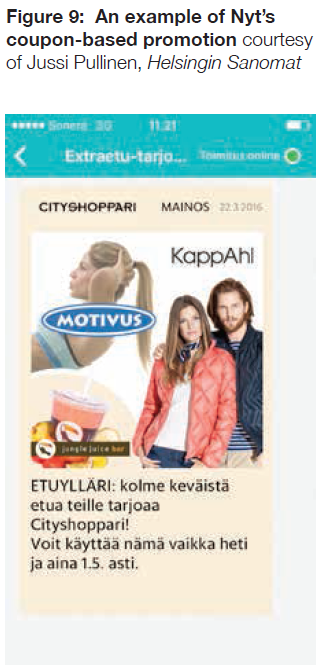

Despite some engagement challenges, they have more users than they did on WhatsApp, and the app does allow commercial opportunities without the fear of breaching the terms and conditions of a third-party platform. The revenue model for the app is based on coupons, contests, and sponsored content rather than display ads. From their data, they know that their young audience is the most resistant to ads, being amongst the highest users of ad blockers.

They run competitions on the app around films such as the Huntsman or Hunger Games. For instance, they gave away tickets to people who sent in selfies with their best Hunger Games pose, he said. Users can also get coupons for local businesses.

They have a clearly marked commercial channel on the app for partner content due to strict regulations in Finland on sponsored content, Pullinen said, but added, ‘the users don’t seem to mind if it is good content and meaningful’. The trade-off is that the partnerships are more work than selling banners, but they have bundled the partnerships with other packages for advertisers who want to reach a youth audience, he said, helping them to leverage sales from the main brand.

Horizons in Visual Journalism: Mobile-First Video and VR

‘The future of storytelling is visual’, New York Times CEO Mark Thompson told a crowd of advertising industry representatives at the NewFronts in 2016. NewFronts is the digital equivalent of the upfronts, when advertisers buy airtime ‘up front’, ahead of when a new season of programmes airs. The New York Times has joined digital video producers such as Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu the last few years to tout its video efforts (Bazilian 2016). It demonstrates its focus on video as a way to engage audiences and, just as importantly, to secure premium advertising.

Video has become a focus for many news organisations, who are seeking audience reach through social and mobile optimised short, sharable, and emotionally engaging videos while trying to attract advertisers willing to pay significantly more for video advertising than for traditional display advertising (Kalogeropoulos et al. 2016). As an area that promised audience and revenue growth, video production was one of the few areas of new hiring in 2016, a year that saw cuts in many other areas of content. Publishers are getting higher returns for video ads than traditional banners, and video makes up 35% of online ad spending, according to Hubspot (Kolowich 2016).

As publishers have diversified the platforms they use in distributing video, they have also diversified the formats for video. Social video has become a format unto itself, and animated gifs are common on platforms like Twitter and in mobile offerings such as Quartz’s conversational app. But there is also increasing interest in more high production-value forms of ‘immersive journalism’ (Peña et al. 2010).

In this report, we will focus on emerging video formats including mobile-first, 360 degree video and virtual reality (VR). Major news organisations including El País, the New York Times, and the Guardian have all made sizeable commitments to VR although the market is still developing, and for the Times and the Guardian that commitment has been commercial as well, with teams dedicated to monetising this high impact but also high investment content. The three news groups have taken very different approaches to integrating the content into their existing workflow and organisational structures, which demonstrate the wide variety of approaches that organisations take when developing innovative projects.

New York Times: Mobile-First and Immersive Video

As audiences increasingly go mobile, publishers are exploring mobile-first video formats. The Olympics preview feature, the Fine Line, 16 not only broke new ground editorially, but also commercially. It was the first time that advertising content was integrated in the navigation of an editorial feature.

Using the long lead-time available before the Olympics, the New York Times introduced the Fine Line, a mobile video feature looking at the premier US athletes ahead of the Rio games. The interactive went beyond a single self-contained video into a new mobile-first visual format well suited for the swipe-able navigation of a smartphone.

The Fine Line ‘was the first time that we designed and built the interactives with the mobile as our initial focus’, said Joe Ward, sports graphics editor at the New York Times. 17 On a desktop, there are up and down arrows that lead the reader through each element of the project, but on mobile, this was all achieved through a swipe. Ward said:

So many of our readers come to The Times via their phone that it seemed we needed to make that experience a top priority. The projects were not adapted to desktop until it worked well on mobile.

And the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio gave the New York Times an opportunity to try this ambitious new mobile-first video project for their preview coverage. Ward said:

Every Olympics we try for something new. It may be a new way to shoot something: slow-motion video or different lighting or different cameras angles. This year we used a bit of motion-capture technology.

From an editorial standpoint, the planning began early, a year in advance, in part because in the winter before the games ‘they will begin shutting down access’ to the athletes, Ward said. They looked for the athletes at the pinnacle of their sport such as gymnast Simone Biles, who was a favourite for gold. But they also looked at athletes who had something unique that set them apart, such as swimmer Ryan Lochte’s unique underwater turn or Derek Drouin’s one-of-a-kind high jump approach. The last athlete had a unique, inspiring story: ‘Christian Taylor won gold in the triple jump in London, but knee pain made him change his take-off leg. He won gold again in Rio jumping off his other leg,’ Ward said.

These athletes featured in Fine Line, a unique video-led feature which was intended to highlight the small things that top US athletes did that gave them the edge in their sport. The initial team was four video producers, but the final credits list 35 members of staff including staff who conducted the interviews, shot images and video, worked on the graphics, or were involved in some aspect of the production. Ward said: ‘Once production got started, there were many more hands involved. There was 3D modeling, video rotoscoping, storyboarding, designing, script writing and web development.’

Not only was the Fine Line the first interactive built with mobile first in mind, it also broke new ground commercially, according to Adam Aston, vice president and editorial director, T Brand Studio, the brand marketing unit of the New York Times. 18 T Brand Studio has 100 creators on its staff, which includes ‘writers and editors, designers and photo editors, video producers, developers and data engineers, content strategists, audience development experts’ and client services staff, Aston said, and they have an additional 40 staff from agencies that have been acquired, HelloSociety and Fake Love.

The T Brand Studio was not involved in the Fine Line feature but Aston provided background about the commercial elements of the project: ‘[The Fine Line] was a never-been-done-before package for Infiniti. It included a custom integration of advertising alongside the newsroom editorial content.’

Alongside the four editorial produced videos was a video marked as a ‘paid post’ by Infiniti directly in the navigation, and Infiniti ad content was integrated into the flow of the features. However, Aston said that the Times has strict rules for how they label sponsored content: ‘It’s our goal to clearly differentiate what is a paid advertisement from content produced by the Times newsroom, so that we never confuse our readers.’

These high production advertising projects are all part of what New York Times CEO Mark Thompson said are key elements of the newspaper’s effort to grow digital revenue and develop its video offerings. Other initiatives include the creation of a VR team in 2015, and an executive producer for 360 degree video working with eight New York-based producers. Associate editor Sam Dolnick said, ‘every desk in the newsroom – Sports, Style, Culture, Science, Food – is thinking about VR and 360 video and pitching stories every week’. This investment has both editorial and commercial implications. In a recently published strategy memo, executive editor Dean Baquet and managing editor Joe Kahn write ‘We will train many, many more reporters and backfielders to think visually and incorporate visual elements into their stories’, and they underline that there will be more creative directors and senior editors who are visual experts. 19 These investments are part of an ambition to deliver great journalism, but also part of the Times’ ambition to generate $800 million in digital revenues by 2020. 20

El País: VR and Partnering with External Contractors to Speed Innovation

In addition to mobile-first video, virtual reality exists on the cutting edge of editorial innovation. Like the resource-intensive Fine Line feature, VR takes new skills, not common amongst journalists. Additionally, the technology and the production costs can be high. Each example we will review has a different operational approach.

At El País, they first started working with VR with an external company that they frequently work with on new projects. To integrate VR and other innovative projects, they have created a production unit that project manages them, according to David Alandete, the digital managing editor for El País. 21

El País created VR features and an app to help mark its 40th anniversary in 2016. El País moved early to embrace digital, launching a website in 1996, and in a subsequent phase of development a couple of years ago, they increased their video output. Their goal in producing video has always been to produce something that TV could not, and with virtual reality, they saw an opportunity to blend reporting with an immersive experience, Alandete said.

In the case of their award-winning VR feature on Fukushima, the project was initiated by a reporter, who approached senior editors with the idea of taking readers somewhere they couldn’t go, and this led to their first VR project. ‘We thought it was the perfect example of what we could offer in an immersive experience’, Alandete said.

They had acquired some virtual reality equipment, and they have a partner with experience in producing VR projects. ‘It is very important to partner with small companies who work in innovation’, he said. In this project, the partner helped them manage the complicated editing process.

As part of their growing commitment to VR, they have launched an app and now have a VR camera and an editor dedicated to VR. They have done VR projects in Mexico in the town of Iguala where 43 students disappeared. They recreated the moment just before the abduction. Alandete commented: ‘You get more than just reading the story.’

From an audience perspective, VR has been successful for El País. The Fukushima project attracted a large audience and received an award. The VR project about the students in Mexico who disappeared delivered a large Mexican audience for El País. Both projects were shared widely on social media.

Alandete has developed a process to manage experimentation with new formats, whether that is VR, enhanced newsletters, or chatbots. El País has relationships with external partners that help speed development of innovative projects. Internally, Alandete created a production unit six months ago that project manages the diverse range of projects that he is testing: ‘The project may be VR. It may be an interactive map of US elections. This group makes sure that projects we have in hand are in the daily flow and have appropriate resources.’ It delivers a level of flexibility that allows them to produce a wide variety of innovative digital projects.

As for revenue, he said, ‘being an editor, not everything is going to give you instant revenue, instant readership, but it’s something you have to do because it’s in the DNA of your newspapers’.

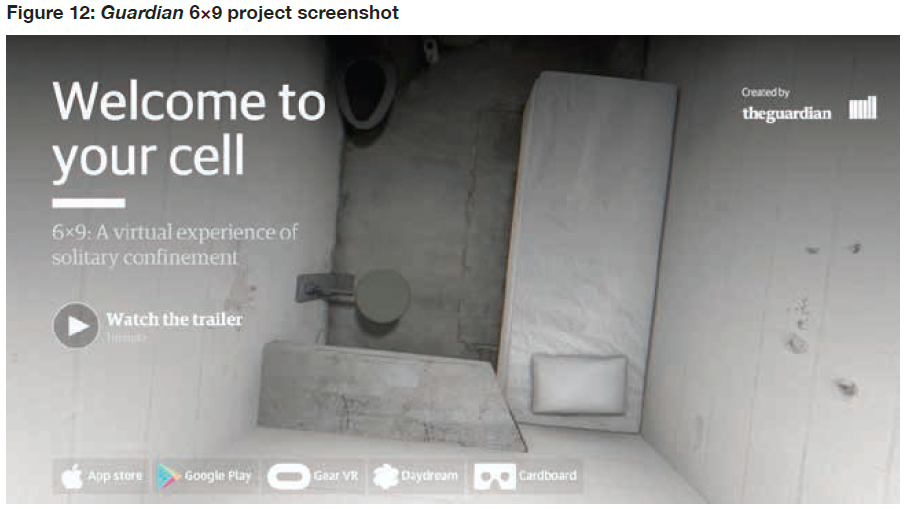

The Guardian’s VR Pilot Projects

The Guardian’s ground-breaking 6×9 project about solitary confinement was launched purely as an R&D project, according to Aron Pilhofer, who served as the executive editor of digital at the Guardian at the time of the project. Now, he is the James B. Steele Chair in Journalism Innovation at Temple University. The project led to a VR pilot project that will give a joint editorial and commercial unit 18 months to test the viability of the format.

Pilhofer had seen Nonny de la Peña’s Syria Project, and it was the first time that the avid gamer understood how VR could be applied to journalism. That project, funded by the World Economic Forum, immerses the viewer in a scene in Aleppo in Syria, in the chaos after a rocket attack. 22 De la Peña’s work uses the Unity video game engine to recreate the scene of an attack based on two handicam videos that the producers of the VR experience found on YouTube.

Writing for Vice’s Motherboard, Christopher Malmo wrote:

Project Syria is a perfect example of what’s possible when new technologies are applied to reporting. Using VR renders the project immersive, going beyond two-dimensional print or video coverage to physically place the viewer into the story. In doing so, they stop being a mere viewer, and much more of a witness. 23

Inspired by de la Peña’s work, special projects editor Fran Panetta approached Pilhofer about doing an ambitious VR project. He decided to propose a VR proof-of-concept, R&D project. They were not thinking about revenue at that point. He knew that the audience would be limited because, while simple viewers like Google’s Cardboard were out, the Oculus Rift and HTC’s Vibe were announced but had not shipped yet. Samsung’s Gear viewer was available but had not shipped in significant numbers.

The sole reason to do it was to make a story, make a piece of journalism using this platform in a way that could only be done on this platform. We wanted to push boundaries journalistically, but also technically, which is why we did this in [computer graphics]. …It was a true VR project rather than a linear 360 video.

They wanted it to be interactive, and they wanted to try some basics of branching narratives.

To fund this ambitious R&D project, Pilhofer looked outside the Guardian. Panetta had a little bit of budget to spend on it, but most of the money, roughly 90%, came from grants and foundation funding outside of the Guardian, including groups such as Tribeca Film Institute, Chicken & Egg Pictures, WGBH’s Frontline in Boston, and the Google News Lab.

Pilhofer managed the project while Panetta acted as director, writer, and producer. ‘What came out blew my mind, and it is one of the things I am most proud of from my time at the Guardian’, Pilhofer said.

In terms of audience and response, he said it was hard to benchmark because there wasn’t a sense of how large the VR audience would be at the time. It was downloaded hundreds of thousands of times, with most of the downloads through the Oculus store. One of the lessons that Pilhofer took away from this was that VR, at least initially, will be an entirely different distribution model. Unlike El País and the New York Times, which both distribute their VR content through an app, 6×9 was distributed as a standalone experience via various mobile and VR app stores. Pilhofer believes that VR ‘could be the most distributed form of journalism that we’ve seen yet’, through Google’s Play store, the Oculus store, Sony’s Playstation store, and Apple’s iTunes store.

In terms of success, the project had a dramatic cultural impact. ‘It had a physical installation that went to several film festivals. It went to the White House. Robert DeNiro was on Jimmy Kimmel Live talking about it’, Pilhofer said.

Despite the cost of VR production, Pilhofer believed that there was a revenue model for VR, especially with what the New York Times is already doing with the format. He sees a range of potential revenue streams including sponsorship, underwriting along the lines of public media in the US, branded content, white label production, and even in-VR advertising. In terms of advertising, Pilhofer said, ‘I have got solicitation from a start-up for this, and it just made my jaw drop.’

The project started talks with Google around VR. The Daydream team approached the Guardian to become a launch partner, offering a substantial sum of money over an 18-month period in return for a guaranteed amount of content. It would not pay for the entire project, Pilhofer said, but he felt that it was sufficient seed capital to launch a VR studio ‘in a way that made sense’.

He proposed an 18-month, self-contained project to Guardian editor Kath Viner and CEO David Pemsel, which would have commercial and editorial staff working in a unit. The project would have to have clear goals. If it met those goals, they would carry on, and if not, they would shut it down.

The editorial side was concerned that the budget was too small to fully fund their ambitions. And if they were successful, the editorial team were concerned that they would be committed to creating a lot of content but that the commercial team would take all the money. Conversely, Pilhofer said that the commercial side was worried that the editorial side would produce

all this super-expensive content and start driving the budget up like crazy. The thing that struck me was that this was everything that is wrong with the newspaper business model in a nutshell where you have no communication, no trust between the business side and the editorial side.

But he was able to allay the concerns of both sides. The editorial side committed to a budget, and the commercial side agreed about how the revenue would be allocated.

Pilhofer believes that this is a good model for how news organisations can explore emerging content areas, by launching bounded projects with clear goals for success and strong collaboration between editorial and commercial teams. But it also shows how news organisations need to create more productive relationships between editorial and commercial teams.

Conclusion

News organisations are experimenting with a wide range of innovative formats, both super-short, sharable, and often ephemeral content distributed via social media and messaging apps and high production value fully immersive virtual reality experiences intended to have a much longer shelf life.

Some of these initiatives, like the New York Times’ Olympics preview feature the Fine Line, require a lot of time, a lot of people, and a lot of money, investments that can realistically only be made by large organisations and recouped by those with significant, often global, audience reach. But other initiatives, whether Rappler’s chatbot, Quartz’s messaging app, or the Helsingin Sanomat’s use of WhatsApp, are much smaller investments with a faster turnaround and not reliant on global audience reach and the resources that entails. Rappler has a total staff of just over 50, and 140journos is a team of just 10 people. Their interesting new experiments clearly show that news organisations do not need hundreds of people, large sums of money, or long lead times to try out new and potentially important ideas.

What all of the initiatives have in common is that they are examples of news organisations thinking ‘beyond the article’, beyond simply posting news items on a website and promoting them via Facebook, both in terms of their editorial ambitions and the commercial aspirations.

Further commonalities include:

- Most content innovation is generally focused on various forms of distributed content enabled by platform companies, including well-known formats like social media but also increasingly messaging apps and virtual reality. In some cases, like messaging apps, news organisations are following audiences to platforms they have already embraced. In other cases, like virtual reality, news organisations are moving ahead of most users.

- These different platforms all offer news organisations the opportunity to reach audiences who are unlikely to come directly to news organisations’ own websites and apps, but also come with the risk that users start abandoning a given platform or that the platform changes how it operates. The opportunities and challenges around the use of messaging and virtual reality platforms are thus parallel to those known for example from social media.

- Commercially, traditional forms of revenue like display advertising and subscription play a small role, and most current and planned business models are based around a combination of other sources of revenue, including native advertising and sponsored content, coupons, partnerships, or the sale of services, where the news content serves as a form of loss leader.

Most of the cases examined here have started with clear editorial goals, but also involve thinking about the business and technology dimension from the outset. They generally involve cross-functional teams with editorial, commercial, and technology talent (an approach more widely adopted by many innovators in digital news, as documented by Küng 2015). In some cases, these teams are in-house, in others, like El País, they involve external partners with expertise not present in the newsroom. They all indicate a willingness to invest and to take a calculated risk on the basis of editorial ambitions and a determination to test out new possible opportunities. This involves placing bets and it requires sometimes hard decisions about where to allocate scarce resources. As a Quartz spokesperson told the technology news site Recode, ‘One of the smartest things a high-growth company can do is decide what not to do’ (Kafka 2016). This applies to legacy media too, as they balance between legacy and digital operations, and balance between exploiting current opportunities versus exploring future ones (Cornia et al. 2016).

To create the space for innovation and the opportunity for growth, companies at every scale and every stage from start-up to storied legacy media must decide not only what to do, but also what they will stop doing so that they can focus on editorial and commercial innovation – not simply for the sake of doing something new but to achieve their journalistic mission and their editorial ambitions in a constantly changing media environment.

References

All URLs were last accessed in January 2017.

Barot, Trushar, and Eytan Oren. 2016. Guide to Chat Apps. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/guide_to_chat_apps.php

Bazilian, Emma. 2016. ‘New York Times Doubles Down on Virtual Reality at NewFronts: New Series Will Focus on Space Exploration, the Olympics and More’, Adweek, 2 May. http://www.adweek.com/news/technology/new-york-times-doubles-down-virtual-reality-newfronts-171177

Benes, Ross. 2016. ‘Are Facebook and Google Really Taking All the Digital Ad Growth?’, Digiday, 15 Nov. http://digiday.com/platforms/facebook-google-really-taking-digital-ad-growth

BI Intelligence. 2016. ‘Messaging Apps are Now Bigger than Social Networks’, Business Insider, 20 Sept. http://www.businessinsider.com/the-messaging-app-report-2015-11

Consunji, Bianca. 2013. ‘Facebook Rolls Out Zero Data Charge Access in the Philippines’, 1 Nov. http://mashable.com/2013/11/01/facebook-philippines/#ZcQTgxNf2sqz

Cornia, Alessio, Annika Sehl, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2016. Private Sector Media and Digital News. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Ferraz, Ezra. 2015. ‘Maria Ressa: The Rappler Experiment’, 30 Apr. http://www.rappler.com/move-ph/events/thinkph/2015/platform-thinking/91569-rappler-experiement-maria-ressa

Kafka, Peter. 2016. ‘Quartz has Cancelled its High-End “Next Billion” Conference’. http://www.recode.net/2017/1/19/14324924/quartz-next-billion-conference-canceled

Kalogeropoulos, Antonis, Federica Cherubina, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2016. The Future of Online News Video. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Kleinman, Alexis. 2015. ‘This App Thinks Conversations are the Key to Better Fitness and Sleep’, 29 Apr. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/04/29/lark-app_n_7152178.html

Kolowich, Lindsay. 2016. ‘31 Video Marketing Statistics to Inform Your Strategy [Infographic]’, Hubspot, 14 June. https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/video-marketing-statistics#sm.0001ib1zgx15ttexusoa495xydobf

Küng, Lucy. 2015. Innovation in Digital News. London: I.B.Tauris.

Lichterman, Joseph. 2014. ‘Q&A: Engin Önder and Zeynep Tufekci on 140journos and the State of Journalism in Turkey’, NiemanLab, 17 Mar. http://www.niemanlab.org/2014/03/qa-engin-onder-and-zeynep-tufekci-on-140journos-and-the-state-of-journalism-in-turkey

Liscio, Zack. 2016. ‘What Networks Does BuzzFeed Actually Use?, Navteq, 22 Apr. http://blog.naytev.com/what-networks-does-buzzfeed-use

Moses, Lucia. 2016. ‘With a Bet on a Platform Strategy, BuzzFeed Faces Business Challenges’, Digiday, 1 Feb. http://digiday.com/publishers/buzzfeed-platform-strategy-business

Newman, Nic. 2016. News Alerts and the Battle for the Lockscreen. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Newman, Nic. 2017. Journalism, Media, and Technology Trends and Predictions 2017. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, David A. L. Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2016. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2016. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org

Peña, Nonny de la, et al. 2010. ‘Immersive Journalism: Immersive Virtual Reality for First Person Experience of News’, Presence 19(4) (Aug.), 291–300. http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/PRES_a_00005

Posetti, Julie. 2015. ‘The Powerhouse behind Rappler.com #WomenInMedia’, WAN-IFRA, 13 May. http://blog.wan-ifra.org/2015/05/13/the-powerhouse-behind-rapplercom-womeninmedia

Pullinen, Jussi. 2016. ‘We’ve been Delivering News over Chat since 2014: Here’s What we’ve Learned’, Medium, 27 May, https://medium.com/@jussipullinen/weve-been-delivering-news-over-chat-since-2014-here-s-what-we-ve-learned-1637c20a78f9#.3bvxf2fw0

Turtola, Illona. 2016. ‘Seminar Report: Quartz: “A Mobile-First Approach to News”’, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 7 Nov. http://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/news/seminar-report-quartz-mobile-first-approach-news

Zuckerman, Ethan. 2014. ‘140journos – When Citizen Media Filled the Reporting Gap in Turkey’, My heart’s in Accra, 13 Mar. http://www.ethanzuckerman.com/blog/2014/03/13/140journos-when-citizen-media-filled-the-reporting-gap-in-turkey

List of Interviewees

Positions are those people held at the time they were interviewed.

- David Alandete – Digital Managing Editor, El País

- Adam Aston – Vice President and Editorial Director, T Brand Studio

- Brian Dell, Creative Director, Quartz

- Sam Dolnick – Associate Editor, the New York Times

- Gemma Bagayaua Mendoza – Head of Research and Content Strategy, Rappler

- Nam Le – Chief Technology Officer, Rappler

- Engin Önder – co-founder, 140journos

- Adam Pasick – Push News Editor, Quartz

- Aron Pilhofer – James B. Steele Chair in Journalism Innovation at Temple University

- Jussi Pullinen – Editor, Helsingin Sanomat

- Joe Ward – Sports Graphics Editor, the New York Times

About the Author

Kevin Anderson is an international media and communications consultant who has worked with major news organisations and industry groups around the world including Al Jazeera, Network18, Trinity-Mirror, WAN-IFRA, and the Eurovision Academy, the training division of the European Broadcasting Union. He has worked on a range of projects with these organisations, including data journalism training and strategy, social media strategy, audience development and engagement, as well as product development and digital transformation.

Kevin has more than 20 years of experience in digital journalism, including serving as the BBC’s first online correspondent outside of the UK, based in Washington from 1998 to 2005, and also serving as the Guardian’s first blogs editor and first digital research editor. Most recently, he was a regional executive editor for Gannett in the US.

Acknowledgements

I would first and foremost like to thank the dozen journalists, editors, and commercial leaders who took time out of their busy schedule to discuss their projects either via phone or email and spoke with great candour about their goals, their efforts to integrate these innovative projects into their operations, and the challenges that they faced. Innovation has become much more focused as news organisations adopt product development frameworks, but it is still a process of experimentation. The respondents’ openness to discussing the innovation process, what works and what has not, is key to helping other news organisations as they experiment. Not all experiments succeed, and knowing which ones did not and why is key to the industry navigating this time of dramatic change.

I would also like to thank Max Foxman, a PhD candidate at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. His thoughts about the challenges of integrating innovation into traditional journalism workflows helped inform the section on VR, and form the basis of his dissertation research.

I am also grateful for the help and support from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, including Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, and Alex Reid.

Published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism with the support of Google and the Digital News Initiative

- http://nytlabs.com/blog/2015/10/20/particles ↩

- Engin Önder, co-founder 140journos, interviewed by Kevin Anderson, 19 Dec. 2016, via email. ↩

- Engin Önder, co-founder 140journos, inteviewed by Kevin Anderson, 23 Dec. 2016, via email. ↩

- Adrienne Lafrance, https://www.niemanlab.org/2012/08/in-the-philippines-rappler-is-trying-to-figure-out-the-role-of-emotion-in-the-news/ ↩

- Gemma Bagayaua Mendoza, director of research and content strategy, Rappler, interviewed by Kevin Anderson, 14 Dec. 2016, via Skype. ↩

- ‘Archive of Agos Alert Maps from Past PH Typhoons, Floods, and Earthquakes’, Rappler, 31 Oct. 2014, https://www.rappler.com/move-ph/issues/disasters/73580-agos-alert-relief-maps-list (accessed Jan. 2017). ↩

- https://ph.rappler.com:443/campaigns/fight-corruption ↩

- http://wearesocial.com/sg/blog/2016/09/digital-in-apac-2016, slide 123. ↩

- ‘#ProjectAgos: A call to action’, Rappler, 20 Sept. 2013, https://www.rappler.com/move-ph/39377-introducing-project-agos (accessed Jan. 2017). ↩

- Nam Le, chief technology officer, Rappler, interviewed by Kevin Anderson, 14 Dec. 2016, via Skype. ↩

- Gemma Bagayaua Mendoza, director of research and content strategy, Rappler, interviewed by Kevin Anderson, 14 Dec. 2016, via Skype. ↩

- Nam Le, chief technical officer, Rappler, interviewed by Kevin Anderson, 14 Dec. 2016, via Skype. ↩

- http://www.rappler.com/technology/social-media/140265-raprap-rappler-bot-at-your-service-facebook-messenger ↩

- Adam Pasick, push news editor, Quartz, interview with Kevin Anderson, 9 Dec. 2016, via Skype. ↩

- Jussi Pullinen, news editor, Helsingin Sanomat, interviewed by Kevin Anderson, 21 Dec. 2016, via Skype. ↩

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/08/05/sports/olympics-gymnast-simone-biles.html ↩

- Joe Ward, sports graphics editor, New York Times, interviewed by Kevin Anderson, 11 Jan. 2017, via email. ↩

- Adam Aston, vice president and editorial director, T Brand Studio, New York Times, interviewed by Kevin Anderson, 11

Jan. 2017, via email. ↩ - http://www.nytco.com/from-dean-and-joe-the-year-ahead ↩

- https://www.ft.com/content/5829e768-6a4a-11e6-ae5b-a7cc5dd5a28c ↩

- David Alandete, digital managing editor for El País, interviewed by Kevin Anderson, 5 Jan. 2017, via Skype. ↩

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160301054223/http://www.immersivejournalism.com/project-syria-premieres-at-the-world-economic-forum ↩

- https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/jp5jx3/virtual-reality-is-bringing-the-syrian-war-to-life (2014). ↩