Executive Summary

- In the past three years, virtual reality (VR) journalism has emerged from its early experimental phase to become a more integrated part of many newsrooms. At the same time, technological advances have made the medium available to consumers, especially in the form of 360 videos watched on smartphones, sometimes supplemented by a cheap cardboard headset.

- VR has been compelling both for journalists and for news brands, though some organisations – especially publicly funded broadcasters – have held off on making large investments. Key motivations for those that have invested, for example by launching VR apps to audiences, have been brand innovation credentials and positioning for the future.

- The proliferation of content created through experimentation is solving some of the challenges involved in VR/360 storytelling. Journalists and news organisations are devoting more time to thinking about what works in VR, and as a result news VR is expanding beyond its early documentary focus. However, most news organisations admit that there is still not enough ‘good content’ to drive an audience.

- Most news VR is still actually 360 video rather than fully immersive VR, and is most likely to be viewed on a mobile device used as a ‘magic window’ or in a browser by current audiences. This has made it more accessible to consumers but does not give them the immersive experience delivered by a high-end (and more expensive) headset.

- News organisations using VR tend to have a central, often multidisciplinary team to provide editorial leadership and to commission, edit, and publish content, but train journalists across the organisation to film 360 footage.

- Many news organisations have used partnerships with tech companies such as Google and Samsung to expand their VR operations. But monetisation remains a central challenge for news VR: no one has yet cracked either ad- or subscription-based models for making the technology pay.

- Major technological challenges remain, particularly around the cost and consumer take-up of headsets. Production costs are still high, though technological developments and cheaper cameras have already lowered the entry point.

- VR news still has a poor understanding of its audience both in terms of content, content discovery, and attitudes to the technology and hardware.

- To deliver the promise of VR for its audiences, the news industry now needs to work together. To ensure the frictionless user experience needed to make VR an appealing mass-market media proposition, the industry must present a united front when lobbying the tech platforms.

Introduction

In 1910, an American engineer called Lee de Forest used a new invention, ‘wireless’, to broadcast Italian tenor Enrico Caruso’s performance from the Metropolitan Opera House. He and others like him foresaw that wireless – which at the time was just a substitute for wired telegraphy – could be a new medium. 1

A century later, the parallels with Virtual Reality (VR) are remarkable. A technology developed in labs for largely military and industrial applications, with the power to provide intense immersive experiences in virtual worlds, is finally becoming available to consumers. The purchase of Oculus Rift by Facebook for $2 billion in March 2014, and announcements about investment in VR by other tech giants, led to enormous excitement about VR.

But what will consumers use it for beyond gaming? The challenge is now on to find good user cases for the technology. It seems no industry can ignore its potential: the challenge is being taken up in medicine, architecture, the travel industry, real estate, education – and journalism. 2

The potential for immersive journalism was first explored by VR pioneer Nonny de la Peña in 2010. De la Peña described how it would allow audiences to enter stories, to explore the ‘sights and sounds and possibly the feelings and emotions that accompany the news’ (Peña et al. 2010). In just a few years those early experiments moved from the labs to the newsroom. The possibilities VR offers to transport viewers to places and events – to understand the world in new ways – is being realised step by step.

Jarrard Cole, Executive Producer from the Wall Street Journal, says that as soon as he shows journalists VR, they are usually hooked:

Pretty much every person that I can get a headset on and show them one of the stories we’ve made starts spewing out ideas. War reporters are always very excited to say, ‘You have to get me one of these cameras so people can see what I’m seeing’. 3

But in 2014, the promise of storytelling in the new medium of VR remained elusive. Early experiments are captured in two excellent reports: Virtual Reality Journalism (2015) from the Tow Center and Viewing the Future? Virtual Reality in Journalism (2016) from the Knight Foundation. 4 This report takes up the story where they left off. 5

Despite the technological parallels of a century ago, what is very different today from the early days of radio is the incredible pace of change in VR. This report provides an overview of developments in the news industry in early 2017 – but in such a fast-moving world, it can only be a snapshot of one moment in the evolution of the new medium.

The developments in technology include the launch of high-end consumer headsets (including the Oculus Rift, the HTC Vive and the Sony PlayStation VR). Perhaps more significant for news organisations, smartphone-based headsets – notably the Gear VR (UK launch December 2015) and the Google Daydream (UK launch November 2016) – offered far more affordable solutions for consumers to enjoy a slightly more limited version of high-end VR. 6 The introduction of Facebook 360 and YouTube 360 platforms have enabled news organisations to publish 360 films without investing in their own players, and both now offer live 360 VR.

On the production side, consumer 360 cameras have made low-cost 360 filming possible. High-end VR cameras also improved, although not as fast as many hoped. And new tools are beginning to make the post-production of 360 video simpler.

The New York Times, which led the way with its VR app, committed in November 2016 to publishing a daily 360 report, now displayed prominently on its home page and news app. Many other news organisations have launched apps intended for viewing on cardboard headsets, introduced 360 players to their websites, and published regular VR content. Some now prominently feature ‘virtual reality’ sections in the top navigation of their websites – for example, Euronews, CNN, Blick.

When the Google Daydream VR platform and headset launched in the USA and UK in November 2016, it included apps from a number of leading news brands – the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, CNN, USA Today, the Guardian, the BBC, and ARTE. This marked a moment of change for VR in news: significantly, these apps were promoted alongside games.

So is it working? How much good VR news content is there today? Has VR news now moved beyond experimentation into becoming a potential revenue stream? And will news content ever convince consumers to buy and use VR headsets? On these questions hang the future of VR for news.

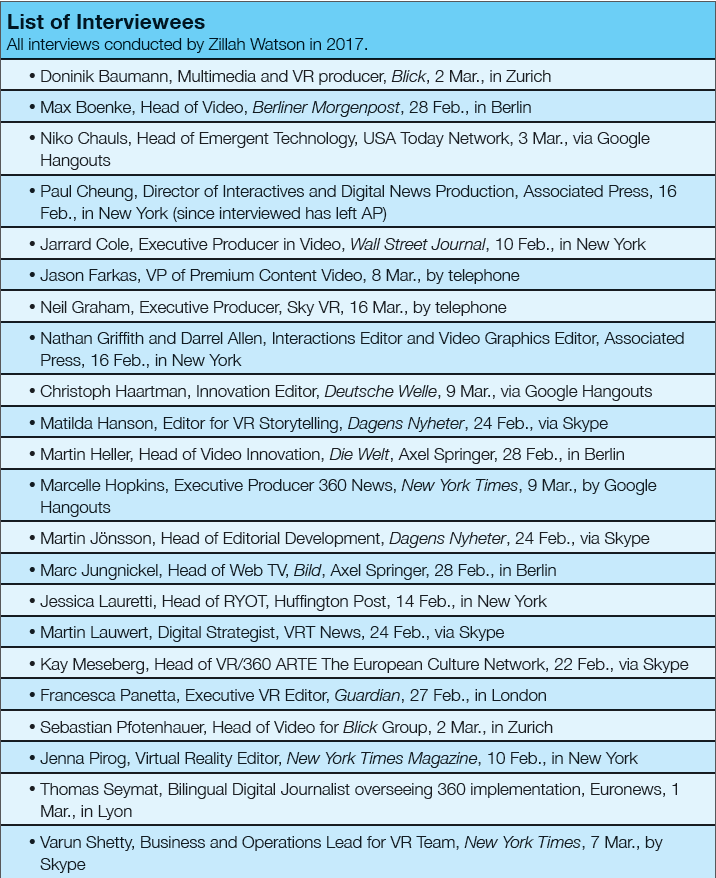

To answer them, I interviewed more than 20 VR experts from leading newspapers and broadcasters (mostly legacy news organisations) in the USA and Europe in February/March 2017. The aim of this report is to provide a snapshot of the current state of VR in the news industry in Europe and the US in early 2017 and the motivations driving it.

The news organisations employing those I interviewed included the New York Times, USA Today Network, Die Welt, Blick, Dagens Nyheter, ARTE, the Guardian, Sky, and Euronews (see full list of interviewees at the end of the report). They are all organisations that champion digital innovation and began experimenting with VR in some form in the last 12 to 36 months. They include both publicly and commercially funded news organisations from a range of media traditions. The interviewees were directly involved in developing, creating or commissioning VR and generally had editorial roles. Almost all the interviews were conducted face to face.

I chose not to concentrate on VR production companies specialising in news, although there are many interesting examples. And because I have been involved in developing experimental VR for the BBC, 7 I have not used the BBC as a specific case study to avoid any conflict of interest, although I do refer to publicly available BBC examples and research where appropriate.

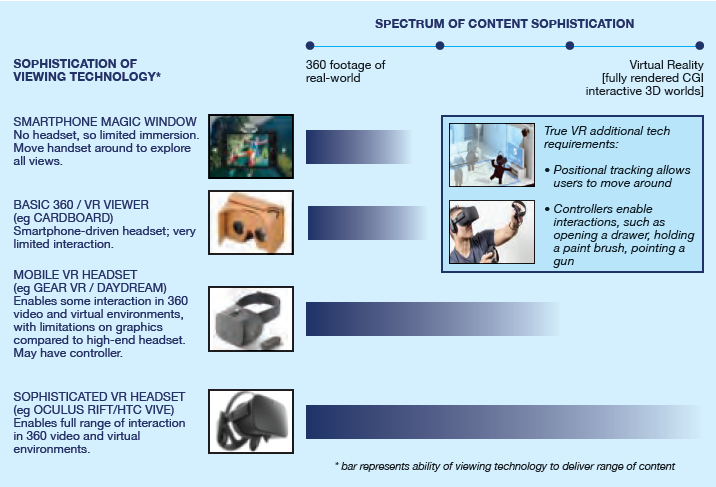

Though some still draw a distinction between ‘true VR’ and 360 video,8 most of the media now refer to 360 video as ‘VR’. Once the New York Times launched its VR app (for 360 films to be viewed with Google Cardboard) there was no going back. For the purposes of this report I include all these experiences, but will make a distinction between VR intended for a VR headset, and 360 viewed on a mobile device, as a ‘magic window’ or in a browser. Figure 1 maps the terrain in terms of the two main dimensions – viewing technology and content.

Figure 2: Devices delivering news VR Adapted from ‘VR Market Review for the BBC’, Tim Fiennes, BBC Marketing and Audiences, August 2016

I begin by considering the current drivers for investment in VR by news organisations. Then I turn to the progress that has been made in creating VR/360 content for news and what the early VR newsroom looks like. Finally I set out the challenges that remain to deliver VR news to audiences, particularly resulting from the complex interdependency of technology and platform developments alongside new forms of content.

VR and News: What’s the Attraction?

Why News Got on Board for VR

It is hard for media organisations to avoid the calls to innovate in VR. From the EBU News Assembly to the Online News Association (ONA) and the Global Editors Network (GEN), VR has been a hot topic. In Vienna June 2016, the GEN adorned its banners with pictures of Mozart wearing a VR headset. In 2017 the GEN’s title is ‘From Post-Truth to Virtual Reality: Navigating Media’s Future’. All those interviewed for this report have become sought-after speakers for such events.

Yet even if VR offers future opportunities for news, the audience is still small today, and investing in an emerging technology that is rapidly changing might appear risky. So it is worth examining the drivers for news investment in VR.

Journalistic curiosity has been a significant factor. Jenna Pirog, Virtual Reality Editor of the New York Times Magazine, says journalists have enjoyed the opportunity to experiment: ‘New tools don’t come along very often, a new medium doesn’t come along very often, so that’s a big challenge and an exciting time.’ 9

Paul Cheung, then Director of Interactives and Digital News Production at Associated Press (AP), has overseen the introduction of many other digital initiatives and notes that VR plays very differently with journalists from other bets on the future of news: ‘For automation and AI [journalists] just think the robot is going to replace them. Whereas 360 is about creative energy – we’ll be able to cover stories that we probably found quite dull, differently.’ 10

Beyond journalistic excitement, the motivations for early investment have centred on wanting to be first to innovate in this new storytelling technology, and/or explore the new business models potentially associated with it. Being involved in developing a new medium from the start was a common theme. Niko Chauls, Head of Emergent Technology at USA Today Network, stresses that:

the organisation recognised a strategic opportunity to position ourselves as expert news storytellers in a new medium. The production of who and what we are is shifting from a traditional newspaper company into a digital media pioneer. This is having an impact on that, as is the recognition that currently the people who are consuming VR content in VR and in 360 are a new and younger audience that we want to pursue. 11

Paul Cheung of AP makes the contrast between the news approach to VR and how slow the industry was to understand the Web:

This is an opportunity for the news industry to stay current and ahead of the curve. I feel like the news industry is having a role in shaping the outcome of [VR and 360], which is vital because that means in the early stages we are thinking not only about how to tell the story but what will the business model look like. 12

Jessica Lauretti, head of the VR production agency RYOT at the Huffington Post, agrees:

[in 2016] every single media company was rethinking their brand, rethinking their business model, rethinking their organisational structure, rethinking what were the skills that they needed for the newsroom of the future. Legacy news is trying to catch up. They know [VR] is part of the future and they need to get involved on the ground floor and help develop what it is. 13

Interest in future revenue models associated with VR forms part of that interest. For example, after stressing the primary motivation of visual journalism and storytelling, Varun Shetty, Business and Operations Lead for VR at the New York Times, adds:

I think the company has really focused on becoming a subscription-first business. We also rely on our advertising revenue, but we think that VR could be an active revenue stream in the future. And that’s something that we’re exploring now, whether it’s through advertisers, or through relationships with platforms. We’re trying to suss out whether there is a full business case for VR. 14

All this matters too in terms of brand credentials: for news organisations at the forefront of VR, demonstrating that they are a forward-thinking brand has been significant. Being seen as the industry leader was a driving factor for the New York Times and this was reflected by many others. 15

Sebastian Pfonenhauer, Head of Video for the Zurich based newspaper Blick says: ‘For us it’s very important to be innovative. We see VR as a game changer and started last year because we think this will be the next big thing.’ 16

Martin Heller of Die Welt adds: ‘It’s in [Die Welt’s] DNA to be innovative in storytelling especially in the digital area. So there is for us no question that we are going to work with new technologies.’ 17

VR Investment: Some Caveats

Focusing on examples of news organisations that have moved beyond early experimentation to launching VR apps might suggest that those organisations that do not invest heavily in VR are less forward-thinking. However, given the limited current audiences, other priorities may have more relevance. Continuing experimentation and watching the market remains a sensible position for many organisations.

This view is supported by the DPP (Digital Production Partnership), a membership-based organisation in the UK originally founded by the BBC, ITV, and Channel 4. It describes itself as working across the media supply chain to make ‘fully digital, global, internet-enabled content creation and distribution work for all’. It has maintained that the television industry, at least, does not need to rush into full immersive experiences.

After reviewing high-end VR at the Consumer Electronics Show in 2017, the DPP recommended that broadcasters and television production companies

keep a watching brief, but to feel no pressure to act just yet. If ever there was an area where it is appropriate to be a follower rather than an early adopter, this is it. There is a huge amount of technology development to play out – and vast amounts of R&D cash still to be spent – before immersive experience surfaces. (DPP 2017a)

And in the DPP’s 2017 predictions they advise:

immersive technologies – Virtual Reality, Augmented and Mixed Reality and 360 ̊ Video – will become established as available media formats. But the next two years will be more characterised by the technical and commercial work required to commoditise those formats than huge consumer take-up. The areas in which immersive technology will have greatest impact will be in non-broadcast content production – particularly in gaming, training and branded content. Broadcasters will continue to explore 360 ̊ video in news, current affairs and sport, where it is an affordable addition to their services that doesn’t disrupt the broadcast chain. But we won’t see immersive technology impact on other areas of TV content in the next two years. (DPP 2017b)

Belgian Flemish-language public broadcaster VRT News provides an example of a news organisation that has made a conscious decision not to make VR a strategic priority at this stage. Their VR experiments include acclaimed journalism 360 films in 2016 filmed in Syria. 18 But they argue that they need to prioritise other innovation projects first and also have a commitment to remain focused on audience/user needs for digital development.

Maarten Lauwaert, VRT News’ Digital Strategist, says their user testing suggested that the audience just isn’t ready for VR yet and that there needs to be greater adoption of the technology first. 19

He endorses the DPP’s view that, for now, it’s fine to leave VR to the gaming industry:

When a bigger group of youngsters starts wearing VR [headsets], then we’ll be there… it feels like a platform where the artists and the gaming industry can have their fun and try things out and push the adoption rate, and then we’ll get in once it’s time for us. 20

For publicly funded broadcasters such as VRT, Radio Télévision Suisse (RTS) in Switzerland and Deutsche Welle in Germany, moving ahead with VR beyond experimentation is hard to justify until there is greater audience interest in VR. Mounir Krichane, project manager at the digital lab at RTS, echoes this view: ‘One of the biggest reasons why we have not moved beyond experimentation is clearly the relatively low adoption of VR in Switzerland.’ 21

In the commercial world, the same considerations may apply to smaller news outlets. Newspaper Berliner Morgenpost experimented with VR to create an interactive 360 mobile app to show how refugees lived in Berlin, in sports halls and hostels. 22 The paper’s motivations were both curiosity to understand VR’s storytelling potential and finding ways to distinguish themselves from other local papers: ‘We have a lot of local newspapers in Berlin. The competition is probably the hardest in all of Europe. We’re constantly trying to do things that others can’t do,’ says Max Boenke, Head of Video. 23

He described the paper as still at the experimental stage for VR. He argued that the costs of the technology would need to come down to make VR more viable for a small regional paper. 24

Most of those I interviewed endorse the view that smaller news organisations should at least experiment to understand the possibilities. Consumer 360 cameras have lowered the barrier to entry and enable anyone to begin to understand the basics of VR storytelling. Varun Shetty from the New York Times says:

I think it’s just important as these things evolve to stay on the cutting edge of the different ways that audiences are able to consume information and consume news. This seems to be one that technology companies are betting on. And they control so much of the distribution now that it’s important to understand how you can work with it. 25

The Content Challenge

Betting on VR Technology

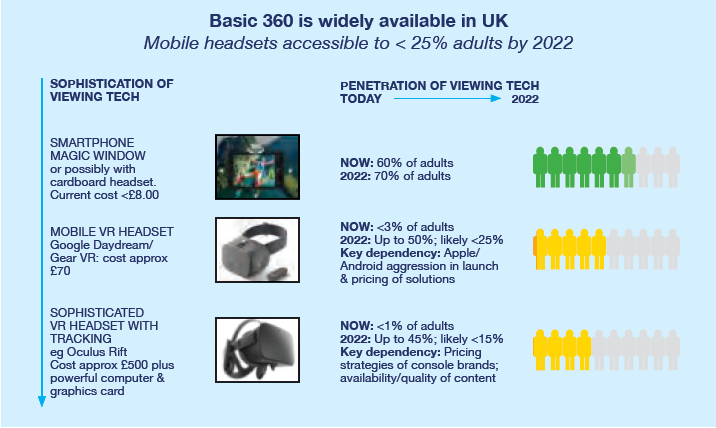

VR is dependent on the development and consumer adoption of headsets, not just great news content. Some early industry predictions about the speed of uptake of expensive VR headsets such as the Oculus Rift have proven highly optimistic. Current estimates put total high-end headset sales (Oculus Rift, HTC Vive, and Sony PlayStation VR) around 2 million worldwide. 26 One might expect journalists to be more sceptical about the speed of adoption than technologists, and they are. For news, the bet is firmly on mobile VR (a smartphone in a headset) as the best way to get content to audiences in the medium term. And the hope is that the technology will converge to enable highly immersive smartphone-based VR experiences.

Varun Shetty from the New York Times explains its strategic focus on mobile:

Mobile feels to me like the cleanest path to mass adoption for VR. I don’t believe that next year people will be spending thousands of dollars on an Oculus Rift or an HTC Vive. I think that’ll happen eventually and certain segments of people will spend that money, and if it does we’ll jump to them. 27

Martin Heller of Die Welt agrees:

I hate discussions like, ‘which is the year of VR?’ 2016 was a year of VR in terms of technology developments. But when we look to a mass audience, it’s more 2020 or 2022 or 2025. We know that it is a question of years until VR goggles are in every household in Germany. 28

Niko Chauls of USA Today is all too aware that consumer technology needs to improve before we see widespread adoption:

We are investing in the space because we believe that the expressions of VR devices and platforms as presented by Oculus, HTC, Microsoft, Samsung, Google are all going to evolve very, very rapidly and become both less of a burden and less cumbersome to wear on your face and take you out of your reality. Price will come in and the quality of content across all genres, not just news, will increase. 29

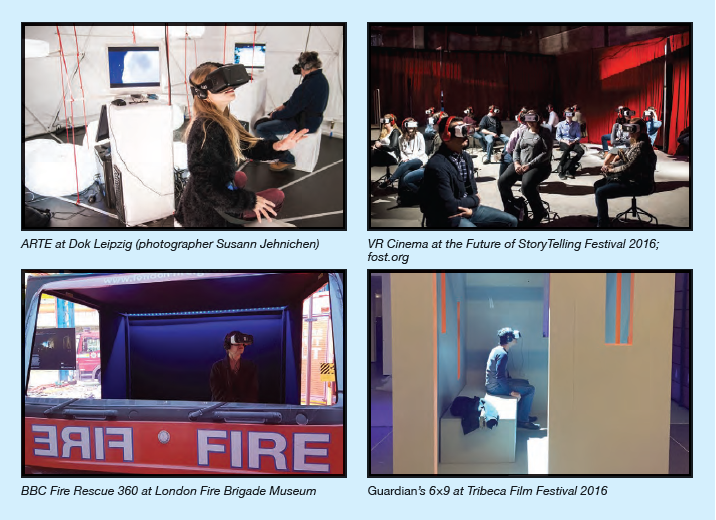

News organisations and production companies continue to experiment with very high-end VR to explore technical and creative frontiers of the medium, but for now you are most likely to see the results at news conferences and festivals such as SXSW, Sundance, and IDFA Documentary Festival. 30

What has developed rapidly in news organisations over the past year is generally 360 video – a spherical video that allows the viewer to look all around. It can be viewed through a VR headset, which is immersive, or watched on a smartphone by moving the phone around (a ‘magic window’) or on a computer using a mouse to move around. 31

Figure 4: UK VR headset projections (August 2016) Adapted from ‘VR Market Review for the BBC’, Tim Fiennes, BBC Marketing and Audiences, August 2016

And 360 video comes in a number of forms – from short films created on consumer cameras intended for mobile viewing through to expensively produced VR films designed for headset viewing.

There are different levels of audience experience, requiring different levels of production effort. Viewing that content through a headset is what makes it VR. The better the headset (and the content) the more magical the experience will be.

Rapid Development of News Content

The lead taken by the New York Times has driven interest in VR across the industry, and almost everyone I interviewed listed the paper as an inspiration. So does the Times regard itself as having moved beyond experimentation? Varun Shetty says:

With the Daily 360 we now we have hundreds of 360 cameras spread across our bureaux throughout the world, with hundreds of reporters being trained on them … we’ve produced over a hundred Daily 360 films and over 25 longer-form NYTVR films. So I think we’re squarely out of the core experimental phase there. 32

Niko Chauls, of USA Today Network, describes his organisation’s journey from creating the ground-breaking 2014 VR journalism project ‘Harvest of Change’: 33

We recognised the potential of VR as a new storytelling medium in 2014 and began laying the foundation for understanding it and creating compelling experiences through the lens of news and journalism … By 2016, we had launched the first weekly news series, ‘VRtually There’. 34

USA Today says it will launch the second series of ‘VRtually There’ soon. The move from individual pieces of content through to formals and series marks another change in the evolution of VR content apparent in 2017. The rise of the VR series drew comment at the Sundance Festival 2017, 35

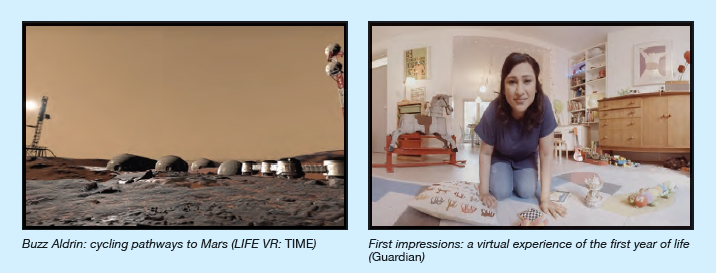

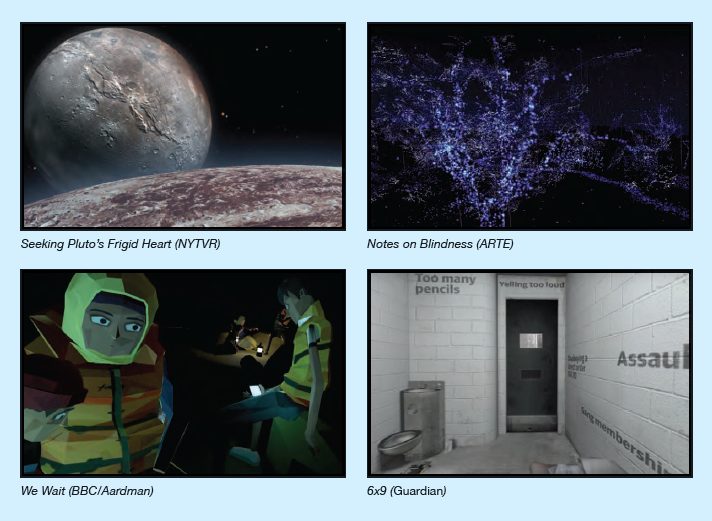

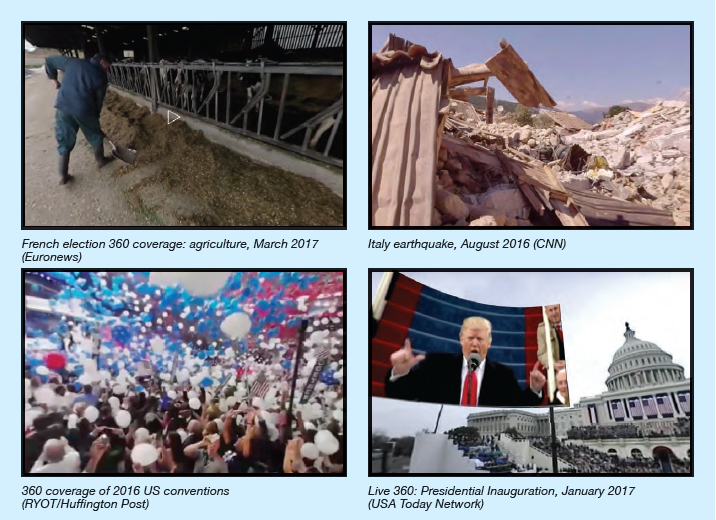

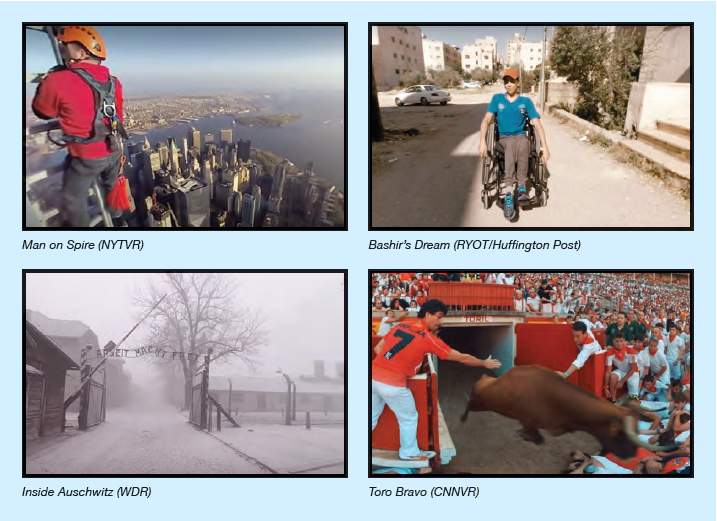

Three years later, in early 2017, we see an enormous range of VR content. In 360, that includes everything from high-end documentaries through to short features for mobile viewing, and for hard news includes foreign reports in war zones through to live 360 coverage of events such as the Democratic Debates in 2016 and the US Presidential inauguration in 2017. 36

Technology developments and the reduced production costs associated with these are partly responsible for speeding up the pace of experimentation and allowing a greater variety of 360 news content. Small consumer 360 cameras that self-stitch 37 enabled short-form VR news content to be produced at low cost, with straightforward integration into existing post-production workflows. And speed is clearly vital to news: the BBC’s first fast-turnaround 360 news report in November 2015, showing Paris after the terror attacks, was shot and published in an afternoon. That simply would not have been possible before. 38

Low-cost cameras can be distributed to bureaux around the world: this model has been followed by the New York Times, CNN, USA Today, Euronews, the BBC, and others. The downside is that the footage is relatively low quality, though acceptable for viewing on a mobile device. But it is only a matter of time before the technology improves.

German tabloid Bild describes most of its content as just 360 video, rather than VR, because it is not intended for headset viewing, with the exception of one film created with Jaunt VR. 39 Bild does not currently have its own player, but has produced a number of foreign news reports which it has published on YouTube 360 and embedded in its website. 40 Marc Jungnickel, Head of Web TV at Bild, told me that improvements in cameras had been significant in allowing the storytelling in 360 to develop for news: ‘With journalistic content if something happens today you can’t wait for four weeks till your story is produced.’ 41

As a result, there are currently broadly two types of VR content being created by news organisations:

- Documentary-style 360 films, usually five to 15 minutes long, and often with high production values with a desire for audiences to view them on VR headsets. These are usually delivered via apps.

- Short-form 360 (under two minutes), generally intended for magic window/browser viewing, usually produced relatively quickly and cheaply. These are often intended for distribution on social channels (YouTube 360/Facebook) and share some editorial features familiar to social video. 42

The New York Times is producing both: high-end content distributed via their NYTVR app, and the Daily 360 – short, engaging 360 videos to be viewed in a browser or smartphone (but also available in the NYTVR app).

High-end VR content remains more time-consuming and costly to produce (and highly experimental if it is pushing technical boundaries). The costs are added to by the need to create different versions for different distribution platforms. Nothing is straightforward in VR yet.

Quality of Experience versus Reach

Whether news organisations opt to do low-end 360 or high-end VR (which may be 360 video or CGI based) comes down to a decision between the quality of experience and reach. This decision affects many things, from the production costs to the method of distribution (see chapter 3).

Thomas Seymat, the 360 lead for broadcaster Euronews, explains that they chose to focus on low-end mobile 360 for maximum reach: ‘We wanted to invest where the audience already was and not go down the road of a specific app, because we can’t guarantee the audience, and it’s very expensive to build and maintain.’ 43 (Euronews 360 content is distributed via social channels and on their website, in 13 languages.)

It has become common to describe 360 video as a ‘gateway to VR’ – even when viewed in a browser. But it is too early to say if it will drive people to try VR in headsets. It is a gateway to VR production because it is easier to create. And it could develop as a compelling form of visual journalism in itself. Sebastian Pfotenhauer says for this reason VR is perfect for a tabloid like Blick, and the New York Times recently announced a greater focus on visual journalism in its 2020 report. 44

Creating high-quality VR for headset viewing takes longer and involves additional production considerations – restrictions that can impact on storytelling. These include camera position, limiting camera movement and the way the film is edited. This is primarily to avoid nausea and a feeling of disembodiment for viewers. And creating high-end computer-generated VR requires even more specialist skills such as Unity developers and 3D designers.

Publicly funded broadcaster ARTE chose to focus on higher end material because it wanted to showcase the future. It commissioned some exceptional VR content – across a range of genres including the multi-award-winning VR piece Notes on Blindness. Kay Meseberg, ARTE’s Head of VR, explains:

We are a public broadcaster so we don’t need to think that deeply about revenues. The key drivers for us are more being upfront in terms of innovation. So, for us it’s a question of exploring how might TV look like in the future. 45

The Guardian has followed a similar route, with a high-end CGI-based experience delivered by apps for Cardboard, Gear VR, and Daydream. And Sky is also aiming at the high-end interactive VR for their content.

Organisations like the Guardian have been successful in marketing and promoting their quality VR through prominence on their website and through commissioning content around the VR. The aim is that, even if they haven’t watched it, Guardian readers and the wider industry are made aware that the Guardian is embracing the future with VR. This model, followed by many others including Blick, also helps to educate consumers about VR.

Sebastian Pfotenhauer stresses that Blick’s job does not end with producing and publishing VR: ‘it’s also important to explain the importance of VR and why we believe in VR and think this could be the future, including for journalism.’ 46

Features or Hard News?

Experimentation continues to discover which content genres will work for both headset viewing and for distribution on social platforms like YouTube 360 and Facebook. Marcelle Hopkins, Executive Producer of the Daily 360 for the New York Times, says they have deliberately cast a wide net for their content across every section of the newspaper – from international coverage to sports, from science and health to travel:

There’s some things that are better explained in words, and some that are better explained in photographs, and some with graphics, and we’re searching for those stories where we can do it better in 360. 47

For both high-end and mobile VR, foreign reporting has been something that journalists have been keen to advance in VR.

Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter led the way for VR in the Nordic countries, by launching an app and distributing Google Cardboard in late 2016, following the example of the New York Times. Martin Jönsson, their Head of Editorial Development, talks about their commitment to use foreign-coverage VR for content for their app: ‘Every time we publish, we try to have at least one story that is at the core of what we do when it comes to foreign reporting.’ 48

It is too early to say which genres will prove most successful in driving news audiences to put on headsets or to view on their mobiles. But the discipline of creating and publishing content regularly will start to establish greater understanding of what works both in terms of production and audiences. And the technology now allowing the fast turnarounds necessary for hard news will continue to improve. Meanwhile, while developing a new medium, it is better to explore what types of stories work in VR, rather than be confined to the genres of the past.

Empathy and News

Chris Milk, co-creator of VR film Clouds Over Sidra, famously described VR as ‘the ultimate empathy machine’ in a Ted Talk in April 2015. 49 This fuelled interest in VR’s potential for news. Empathy was one of the promises of VR explored by the Tow Report Virtual Reality Journalism: ‘a core question is whether virtual reality can provide similar feelings of empathy and compassion to real-life experiences’ (Aronson-Rath et al. 2015).

Empathy has been much discussed at documentary festivals and conferences but the debate has moved on. A standard response is that every medium can elicit empathy, but its power to do so lies in the skill of the storyteller. And not one of the subjects I interviewed mentioned empathy when I asked about what stories worked in VR. Marcelle Hopkins of the New York Times questions the very assumption that empathy has a significant role in journalism:

We understand that often the journalism that we’re doing does elicit an emotional response, but I wouldn’t say that it is part of our agenda. So we don’t think about empathy in the way that I think a lot of VR is being used in documentary for example, or campaigns. For us in journalism, it is a medium that allows us to take our audience to places, to allow, to help them to experience something, to absorb sights and sounds of a particular place unedited. 50

Jason Farkas, VP for Premium Content Video at CNN, stresses that, although empathy is an important component of some VR, it isn’t the only one. He wonders if an over-emphasis on empathy in the early days of VR experimentation perhaps limited the range of content explored:

VR for a while was becoming the medium for showing the horrors of war, and showing struggle – a very dark medium. I think that it’s incredibly powerful on that level, but I also think that VR can be delightful and fun. You go to an animal sanctuary and you feel like you’re right up close with these lions and tigers, and that shows you the joyful virtual reality experience. 51

A wise content strategy for any news organisation wanting to draw early audiences to VR should aim to bring delight as well as harrowing reports from war zones. And for those exploring early monetisation models, this must be an important consideration.

What Stories Work in 360?

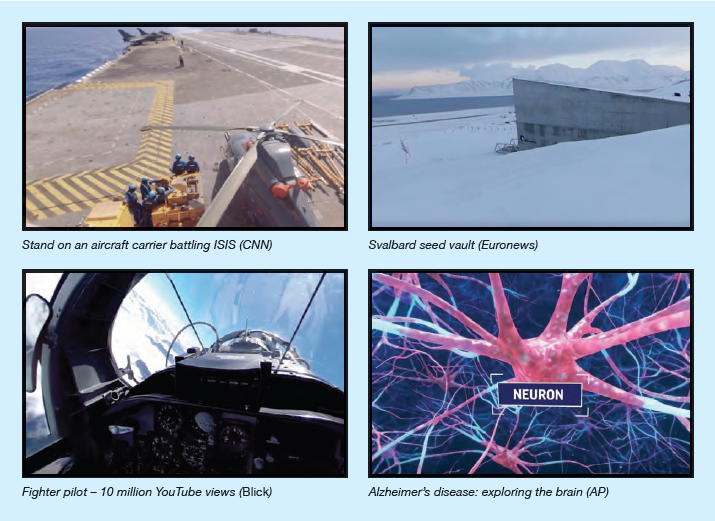

One of my mantras for VR within the BBC has been ‘If you can shoot it better in 169, don’t bother with 360’. CNN’s Jason Farkas is critical of some uses of 360, such as straight interviews, for this reason. He says that when deciding on whether to use 360 at CNN they ask if a story could pass the ‘witness test’:

The witness test is if this story could be better told by someone understanding the environment? Is this a story where presence in the room, or the city, or the square helps you understand the story more deeply? If it’s something visceral – we’ve done things where we’ve jumped out of planes or running with the bulls in Pamplona – those are things that need to be experienced. 52

In terms of storytelling in 360, Farkas says one of the things that has evolved is storytellers and journalists learning to ‘let go of the frame’:

You’ve got to approach every story with the understanding that there may be a key action in your scene that that the viewer may miss. You’ve got to sculpt stories around something being present in an environment, and you can’t rely on shot sequencing, or framing, or zooming, or even editing to add energy to a particular story. You have to rely strictly on the amount of natural action that is happening around the camera. 53

Marc Jungnickel from Bild says two good starting points are stories that enable people to ‘Be them or be there’: ‘Be them’ provides visceral experiences such flying aeroplanes and jumping off cliffs. 54 ‘Be there’ gives you unique access to special locations such as a red carpet, an aircraft carrier, or the closed military base of the German military. 55

For high-end 360 and CGI VR, Neil Graham, Executive Producer for VR at broadcaster Sky, asks of content: ‘Does it warrant being watched in a headset? And does it transport you somewhere?’ 56

The New York Times’ Marcelle Hopkins stresses that there is no rulebook for VR, but concurs that location-based stories work particularly well:

Stories where the place is significant in the story, where it is almost the character in the story. And some sort of action unfolding in front of the camera tends to work really well in 360. One of our most popular pieces was the night that the Chicago Cubs won the World Series. They hadn’t won in 108 years. Our 360 was just the few seconds before they won the game, and then the moment that thousands of people standing in those crowds saw the Cubs win the game. People knew, by the time we published that piece four hours later, that the Chicago Cubs had won. So it wasn’t about delivering that information, but it was about allowing people to be there in that moment when people learned it, and people were crying, they were popping champagne bottles, they were cheering. 57

Some of the techniques being developed have much in common with the development of mobile news video. That means breaking away from TV news conventions such as ‘pieces to camera’. Hopkins discusses the New York Times’ decision to not use reporters on screen:

It was a deliberate decision to make this different from television news reporting. … We do have a few pieces where we’re using voiceover from one of our correspondents. For example, we had a piece from a mental hospital in Venezuela, and our reporter Nick Casey is … guiding us through the hospital … But it’s very different in style than what you would see from a reporter on television. 58

The Huffington Post showed its commitment to VR by acquiring VR company RYOT in April 2016. 59

Indeed several people suggested to me anecdotally that they had found that photojournalists often found 360 video easier to adapt to than video journalists.

Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter started in VR slightly later than some of the organisations I spoke to. They were inspired by the many VR presentations they saw at the SXSW conference in Austin, Texas, in 2016, and the pioneering work of the New York Times. Matilda Hanson, editorial lead for VR, says they were able to learn from the mistakes of others, and used a design-centred thinking approach to establish criteria for the high-end VR content they wanted to achieve:

So the criteria were that we want to take the user to a place where they otherwise wouldn’t be able to go to. We decided that the story is everything – the visual story is everything – but now we’ve come to the conclusion that it’s also very much also an audio experience. 60

The challenge to develop 360 VR as a journalistic tool continues – both for the production craft side and for storytelling. While the International Virtual Reality Photography Association continues to focus on camera techniques for visual storytelling, a number of entrepreneurial journalism schools, including CUNY, Syracuse University, UNC Chapel Hill, and the University of Southern California are running student classes in VR in the US, as is Coventry University in the UK. Many have classes taught by VR news editors. Jarrard Cole, of the Wall Street Journal, teaches VR at the New School in New York. He is inspired by his students:

They went after stories that I would certainly not have had the chance to go after in The Wall Street Journal newsroom. I wasn’t sure how they would pan out, and they were delightful and wonderful. 61

Journalism students are helping to invent and create 360 news formats for newsrooms. For example, Professor Robert Hernandez and students from USC Annenberg partnered with the New York Times to produce a NYT Daily 360 video covering the Presidential inauguration. 62 Figure 9: New York Times Daily 360 – short films across all genres[/caption]

Figure 9: New York Times Daily 360 – short films across all genres[/caption]

Newsrooms and journalism schools have also come together in a collaboration called ‘Journalism360’, backed by Google News Labs, the Knight Foundation, and the ONA. Launched in September 2016 it aims to run events and share knowledge on developments in VR journalism from academics and practitioners, as well as fund a number of experimental projects. 63 Perhaps this will change in time as better production tools develop.

With the exception of ARTE, which commissions content from independent production companies, most news organisations are producing the bulk of content in-house to retain full editorial control, reduce costs, and develop and retain knowledge. Neil Graham, at Sky, explains that this is also because it is difficult to calculate how much money you should spend on VR commissions until you know how much they cost to make. And this is especially unpredictable if you are trying to push creative and technical boundaries in high-end VR. 64

Independent companies may still offer value for high-end VR productions if they bring specialist knowledge.

Multidisciplinary Teams

A common feature of the core teams driving VR, especially those creating higher end VR, is that they are multidisciplinary. VR has provided a focus to create entrepreneurial teams that can cut across the silos in legacy news organisations. These teams bring together editorial leads with software developers and product owners, designers and motion graphics producers with print journalists and photographers, and in some cases also have dedicated business development support to manage tech partnerships.

Francesca Panetta, of the Guardian, says:

I’ve got a cross-disciplinary team which I think is really important. I’ve got a production manager, a journalist who’s moved into film, someone from apps, and the developer. 65

There is also someone focused on partnerships and future revenues. 66

At Sky, Neil Graham describes how interest in VR has resulted in the VR team and interactive team requesting shared workspace so they can collaborate more closely. ‘We have created a new creative environment.’ 67

The fusion of techniques familiar in software development with more traditional news production is also noteworthy – including the introduction of processes such as user testing to iterate content, as used by Dagens Nyheter for example.

That VR has provided the focus to create the types of cross-discipline teams needed across the board in digital news is another positive outcome that should be judged as a success in itself. Whether or not VR is the next big thing, such teams will be ready to adapt to the next disruption. 68

Delivering VR to Consumers

Sufficient VR news content is now being created for the focus to have shifted to include distribution. Content and distribution strategies rest on bets made on headset technology and new distribution platforms. The headsets matter because they are what offer the truly immersive experiences. A high-end headset with positional tracking is required to provide the mind-changing experiences once only available in university labs. 69 They can enable ‘presence’ in a virtual world, created using computer graphics.

Technology Sector Partnerships

In Tim Wu’s book The Attention Merchants, he describes how back in 1996, Bill Gates realised that for the internet to succeed it needed good content. ‘If people are to be expected to put up with turning on a computer to read a screen, they must be rewarded with deep and extremely up-to-date information that they can explore at will’, Gates argued in his essay ‘Content is King’ (Wu, Tim 2016).

And those same words are echoed today in the common assertion that, if people are going to strap a headset to their head, they need a good reason to do it.

The headset manufacturers and platforms are aware that without VR content their technology investments will fail. And they are putting money into seed-funding content or developing production tools. For shrewd news organisations, tech partnerships can offer a way to help finance the development of early VR content. 70

The New York Times NYTVR app launch was in partnership with Google to provide over a million cardboard headsets to subscribers, and the Guardian, Dagens Nyheter, Blick, and others have followed this model. Samsung has partnered with a number of news organisations including the New York Times Daily 360, and Euronews to develop early 360 news content.

Google funded content for the launch of their Daydream VR platform. And money from tech companies is also directly funding better workflows and production tools. For instance, Euronews obtained Digital News Initiative (DNI) money to fully integrate 360 into their production workflows.

Most of these partnerships are short-term and project-specific. Some are said to be more complex, and involve advertising deals too – probably something only larger news organisations can pull off.

The publishers involved generally argue that working with tech partners is not just financially driven; it is necessary to be able to develop and deliver good VR content. It enables news organisations to have a stake in developing and defining processes.

Paul Cheung, from AP, says it helps avoid the situation where

traditionally Facebook and Google develop technology and say ‘here it is’ and everyone has to figure out how to retrofit what they do into it. With VR and 360 I very much feel this is a collaboration with all parties. 71

Niko Chauls at USA Today Network agrees: he says the paper values the ‘exploration, cooperation, and collaboration when exploring areas of VR that have not yet been defined or standardised. Live-streaming being an example.’ 72

Might this dependency on the tech sector have any short- or long-term consequences for the independence of news? Those I challenged argued strongly that, in all these tech partnerships, news organisations retained full editorial control and that this was not an issue.

Varun Shetty, at the New York Times, says:

I don’t think it’ll create issues because the newsrooms are so vigilant about the independence of their journalism. We’re happy to do deals with Google and Facebook and Samsung. But the editorial product is the editorial product in the full discretion and judgement of the newsroom … the news that we’re delivering is still the same news that the New York Times delivers every day. 73

Thomas Seymat, from Euronews, cites the example of his organisation covering Samsung’s exploding phones to argue that there is no question of avoiding damaging stories that involve partners. 74 But that was widely covered by other news organisations; perhaps a harder test case would be to ask whether a news organisation might be less inclined to run an investigative piece that involved a partner, especially when a contract is up for renewal.

To avoid any criticism in the future, news organisations should be transparent about the partnerships. The fact there is no editorial interference now does not mean that it will never occur. And since public trust in news is so fragile, it should not be risked for cash to create VR content.

However, the biggest danger of over-reliance on seed-funding from the tech industry is that it won’t last. News organisations need to find ways to make the technology pay: the longer term monetisation challenges will determine whether news continues with VR, and at what level.

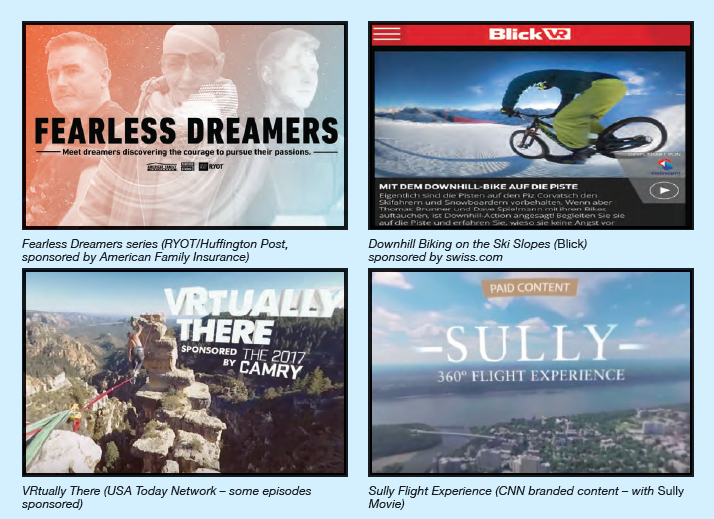

Monetisation: Finding Revenue Models for VR

The digitalisation of news has driven a crisis in the business model of all commercial news organisations, especially newspapers and magazines. Investment in earlier types of digital platform was driven by the need to compete with free online content, and to compete for advertising spend with digital rivals. At the same time, intense cost pressures as organisations fight to stay profitable has meant that such investment decisions in new technology have to be considered carefully – and made to pay for themselves as soon as possible. All of this applies to VR.

‘Everyone is trying to figure out how to monetise VR through ads, but no one has the answers yet’, admits Jessica Lauretti of RYOT. But she adds: ‘I think right now everyone is doing a pretty standard branded content model.’ 75

Those experimenting with this model are not just distributing branded content: they are being paid to create it too – using in-house branded content studios. These include RYOT at the Huffington Post, the New York Times, Blick, CNN, and USA Today Network.

It is perhaps ironic that a technology looking for a content justification in 2017 returns to the model Westinghouse exploited to create content to drive the early radio industry in the US. 76 But native advertising and sponsored content are also being revisited by other areas of news. The growth in branded content by news distribution was one of the hot topics at the Guardian Future Media Summit in March 2017.

As a result, Niko Chauls claims USA Today is already seeing success in monetising VR. They have added a VR arm to their branded content studio, Get Creative, and for their series ‘VRtually There’ created a VR ad unit to produce what they call ‘cubemercials’ – short pre- and mid-ad rolls:

We did that because most of what was out there in terms of monetising VR were people who were taking video ad units and trying to make them work in VR space, and that was a poor expression of shovelware that we chose to eschew and instead focus on creating a made-for-the-medium ad unit. 77

Shortly before I interviewed Chauls I saw USA Today’s attempts to bring on board sponsors in action at a USA Today VR event for potential sponsors held in a cool art studio by the High Line in New York. A Vive demo, allowing users to explore an aircraft carrier and select action footage shot on planes, was being used to show potential sponsors the future of VR.

Those like USA Today who adopted VR early have an advantage at this point, which they may be able to continue to exploit as more providers enter the market. But the future of the medium is so dependent on headset technology developments and adoption that future market conditions for monetising VR are very hard to predict. Even those who adopted and developed VR content early will have to keep running hard to keep up with the technology as well as competition as production costs fall.

VR and News Agencies

For news agencies stepping into VR, the future business model is equally uncertain. To some extent it relies on the wider news industry establishing revenue models that enable organisations to buy in agency content.

US news agency Associated Press is now producing around ten pieces of 360 content a month to test customer appetite. AP’s Paul Cheung explains that agencies reliant on licensing subscription models have a particular problem because it is still early days to work out a price for 360 content:

At the moment we get a lot of interest … but the price point is still in the works, in terms of what is the ROI [return on investment] … Are they video, are they not video, are they being priced as video, are they being priced as something else? So we are still experimenting and trying to flesh that out. 78

Agencies are a good place to identify whether news media see this as content they want to purchase and buy.

The difficulty of putting a price on VR content is being worked through across the industry – from artists’ rates through to production company fees. And because of the different industries converging in VR, a variety of fee structures is colliding. The desire to experiment and see what works has to come before more considered attempts to calculate ROIs.

A News VR Proposition to Win Tomorrow’s Audience

VR news is still in its infancy. Its future will rely on a complex of interdependent advances, most of which are out of the control of the news industry. But news organisations can take decisions to grow their VR audiences, if early revenue models can support further investment.

Better Content

It is perhaps inevitable, since most people I interviewed are content creators, that they see quality content as key to establishing VR news. And that content has to be good enough to justify putting on a headset.

For Max Boenke, Head of Video at Berliner Morgenpost, most of what he sees today just isn’t good enough: ‘I’m afraid that more and more people in news organisations use 360 for stories that are not interesting. Bad content will keep people away from watching it.’ 79

Niko Chauls of USA Today agrees that there needs to be a proliferation of good-quality content.

Nothing is going to be more effective in getting people to consume more than compelling content experiences in any content category, and nothing is going to be more effective in getting people to NOT pick up a VR headset than bad content. 80

But he is hopeful that better content is starting to come through, because of an important shift:

More and more of it is created by storytellers, by content creators. There was a time that we are fortunately coming out of where the vast majority was created by technologists showcasing the technology of VR, and that was not a great thing. 81

At the same time, technology developments continue to provide new opportunities for content, including greater interactivity. Several people I spoke to were keen to exploit the controller that comes with the Google Daydream headset. Samsung also plan to launch a controller for the Gear VR.

Live VR also offers opportunities for news. Some organisations such as USA Today have already begun to explore these – they covered the US Presidential inauguration in live 360. But those I spoke to were split on how significant live VR would be in the near future.

Jessica Lauretti expressed some caution about people rushing into live VR without thinking about the editorial value. ‘I actually think in some ways it’s a distraction and it’s almost a step backwards. The live is the thing about it that people get excited about, and they forget about the actual format of things.’ 82

Nathan Griffith, Interactions Editor from AP, agrees: ‘I’ll be honest, the few live pieces I’ve seen have been very, very underwhelming for me.’ 83

For Bild’s Marc Jungnickel, getting the technology good enough for reporters to take with them is key. He thinks live VR would have enhanced one of the 360 stories one of their reporters did covering refugees on their journey to Europe:

He was with them on one of these rubber boats trying to get over the sea at night and he was doing that in 360. You were barely able to see a lot because it was dark, and they had to take care not to get picked by the military, but you feel the experience of being there with him on the rubber boat and you turn around and you hear the kids screaming and you hear the waves. 84

It is important too that content-led experimentation continues at the high end of VR, even if much of this cannot be delivered to audiences yet, to ensure that new technology and techniques such as virtual embodiment can transfer from the labs to the newsroom in the longer term.

Advances in Technology

Production technology

‘There is no perfect kit yet’, cautions Neil Graham from Sky. 85 Improvements in production technology, from cameras through to simple newsroom production tools that make it easier to produce good content, could help transform news VR. To the extent that content depends on these technological advances, it is not fully within the control of the news industry.

Production tools are beginning to emerge to create and publish VR to different platforms. But for now these are unlikely to be integrated with other newsroom systems and will continue to demand separate processes and equipment. At the higher end, ARTE and the Wall Street Journal have partnered with a Canadian start-up, Liquid Cinema, which is developing solutions to author and distribute VR.

But tools are also needed to create VR for news quickly and simply. One example is Fader – a Web-based VR creation tool currently being developed with support from Google’s Digital News Initiative (DNI). 86 This will enable producers to create VR experiences using 360 photos, video, text, and graphics. Euronews is trialling it to create some unique reports for the French election coverage in 2017. 87

There is also much hope that Web VR (VR experienced through a browser) will democratise VR and do away with the current issue of creating different versions of content for different platforms. The same content could be viewed on a smartphone or an Oculus Rift. This will also have a significant impact on production time and expense.

Nathan Griffith of AP is one of several who hopes it will prove the answer to many current problems:

I think that will go a long way towards breaking down that sort of access barriers. It’s effectively a web page. It gets rid of the platforms. So you have much more rapid development cycle – and you can change that as quickly as you would change a web page. 88

Consumer headsets

Consumer adoption of headsets – and what that means for the user experience around viewing content – is key. VR without headsets is not really VR. Adoption of consumer headsets is unlikely to be driven by VR news content, but news organisations do have a role in educating consumers about VR, both in their news coverage of wider VR stories and when they offer VR to consumers.

Newspapers including Blick and the Guardian have created special VR issues, and used wider content commissions to explain the value of VR.

Marc Jungnickel of Bild was impressed by the VR experience offered by Ikea on a family shopping trip, and believes uses outside news will be helpful in driving interest: ‘The more people get used to wearing these goggles, the easier it will be for us journalists to present content in that way’. 89

But it’s not just the headsets that need to improve, it’s also the user experience around selecting and watching content. Jarrard Cole from the Wall Street Journal argues that those who buy headsets need to be able to discover good news content:

I don’t think I’m imagining a place where somebody’s buying a VR headset because they really want to watch news in it. But once they do have it, there needs to be enough there that they run into some good stories and they know that that’s a thing they can engage with. 90

Nathan Griffith from AP explains some of the problems: ‘There’s often a lot of steps to actually getting content. You have to download an app, or maybe you need a plug-in, or maybe you need to run special software, or need special hardware.’ 91

And finally there is the issue of bandwidth: even 360 videos on YouTube and Facebook are heavy on data. So consumers who are ready for VR may still struggle to watch it at home at present.

It is therefore important for news organisations developing VR to engage in opportunities to take VR out to the public – through events, VR cinemas, and festivals. This not only gives future audiences a taste of what VR can offer, viewed through a good headset, but also allows direct user feedback.

Greater Understanding of Audiences

Perhaps the biggest unknown for VR content (news or other) remains audience appetite. Fundamental questions – such as what sort of content will make users bother to put on a VR headset every day – remain largely unanswered. And those questions begin with content but also include aspects such as how that content is presented on platforms, through to the user experience of finding and viewing that content on a headset.

A couple of VR producers I spoke to joked that, at the moment, most news 360 is still being produced for VR news journalists and the news industry itself. But is VR news being watched by news junkies and early adopters, or is it managing to reach new audiences? We simply don’t know.

A glance through news 360 videos on YouTube shows that viewing figures vary enormously – from Blick’s stunning 360 Cockpit View Fighter Jet 92

The quantity of audience data available for VR content is platform dependent. News organisations with their own 360 players and apps probably have the most data, because they have integrated sophisticated heat-map technology to be able to show where viewers are looking. Other relevant data might include how long people watch a piece of content and how long they will stay in an app, and how much it gets shared.

But Niko Chauls from USA Today Network cautions that any data we do have about VR audiences now may be distorted by the fact that users are still learning how to enjoy VR. He bases this on his own early VR experiences:

I know that maybe the first three times I experienced VR … I was so dazzled by the medium … it wasn’t really about the content. I think my habits and desires as a content consumer weren’t set in VR until I had hours and hours if not days of that under my belt. 93

Is the technology audience-ready?

Producing any content for VR headsets presents another audience challenge. Most agreed that VR headsets are simply not good enough yet, and audiences may struggle to get to the point of watching VR content because of that.

Jenna Pirog from the New York Times thinks we need improvements:

I think it has to look cooler. You can’t really look like a nerd. That was the obvious problem with Google Glass – it had a cool function but they didn’t integrate it to people’s lives. I think it has to work better. Batteries are obviously a huge issue, batteries getting too hot, batteries running out really quickly … And then there is the constant software update. I think it just needs to become more reliable. 94

Many of these limitations were confirmed by some recent ethnographic audience research by the BBC/Ipsos MORI, which sought to understand better the consumption of VR content in the home. The research suggests that there were some limitations to current mobile VR experiences. Problems ranged from the clunky user experience of the headsets to confusion around varying user experience. Content discovery was a particular issue – and the report recommends the need for intelligent curation of content around audience needs. 95 Another recent study indicates that even the furniture we sit on may have an impact on VR experiences: sofas do not make it easy to look all around. 96

While accepting that it’s still early days for VR content, it seems clear that the audience needs to be at the centre of the next stage of VR development. In the end, despite the highly competitive nature of the news industry, rival organisations may need to find ways of working together to overcome such challenges. For AP’s Paul Cheung, there has to be a clear break with the way that news organisations failed to understand the Web:

The way we think about competition is very different from those days. This is such a nascent technology that we need to create a win-win scenario for the media and in order to do it we have to share best practices and we have to share metrics and data so that we can really have a say in how we shape this medium for us rather than the conversation be completely dictated by the technology and platform providers. 97

The collaboration and knowledge sharing by VR journalists is already considerable. But news organisations also need to work together at an industry level: they must now present a united front in lobbying the tech platforms, to ensure that hardware developments, content curation, and user experience serve the needs of news VR.

Conclusion

VR has emerged from its early experimentation phase and is now bedding down in news organisations as they address the challenges of content and user experience. But it is still some years from what it could become – in the same way that, ten years ago, no one could have foreseen the role today of social media.

In part this is why VR is so exciting: we can shape the future, with a genuinely creative technology, with the potential to transform the way news output is made and consumed. Both the news and tech industries are aware of the challenges that need to be overcome. To bring audiences the many benefits of VR, they need to continue to work together to solve these problems.

The following are the key issues that new organisations must address.

Strategy and Investment

Developments in news VR are one of a series of bets that news organisations are making on future initiatives: some will pay off, some won’t. Organisations large enough and with the financial stability to take a long-term view should be betting on VR: it can enhance their brands, and if VR really takes off, early mover advantage is likely to be as critical as it has been for the Web or apps. Forward-thinking organisations want to be positioned to embrace it and don’t want a repeat of how they were left behind by the Web. And to the extent that such tech experimentation is seen as important for the brands, simply doing it could be seen as a success in itself. But there are no guarantees – and it could easily be ten years before VR news really delivers. Or it might be subsumed into another technology.

By contrast, smaller/weaker news brands will need to think more carefully about large-scale investment in VR at this stage. They will struggle to get investment from platforms and may be best doing low-cost 360 investments or partnerships on bigger projects to develop capacity. If they have the funds, they will be able to use the growing VR/360 freelance market. Meanwhile broadcasters (both public service and commercial) face a dilemma: they cannot abandon their core businesses but risk getting overtaken by newer competitors in VR. So they need a clear focus, contained investment, and partnerships with others to learn and keep up to speed. But there is still time – especially for news.

Content

There is a complicated interplay between headset technology, the distribution platform, and content. But content is in the end what news organisations can do most to change, the majority of the technological factors being beyond their control. There still needs to be far more high-quality content to attract audiences – and to stop them turning off. The focus should remain on making great experiences suited to the technology. But there is an inherent problem around quality versus reach: good, properly immersive VR requires headsets, which most consumers do not yet have. Many news organisations justify the current approach of creating 360 as a ‘gateway to VR’ and helping to educate consumers. However, it is still too early to judge whether that will work. The danger is that poor experiences could put consumers off VR.

In fact, 360 is really a ‘gateway to VR’ for production: low-end 360 is now much easier to create and distribute than high-end VR. Until the costs of high-end production come down – which they have to, to make high-end VR commercially viable – 360 may be a good short-term solution to increasing the availability of content. Alongside developments in storytelling, we see some impressive attempts to integrate VR across production, which across the board means that hundreds of journalists have now been trained to shoot 360.

Smartphone ‘magic window’/browser-viewed 360 may develop into a useful form of visual storytelling in its own right, to be viewed on 360 players on news websites and social media. If that were a proven way of bringing in new/younger audiences, then it might have great value to news. But low-end 360 will not help drive any future market for VR headsets.

News organisations investing in VR need to be creative about finding opportunities to take VR out to their audiences – through VR cinemas, festivals, and events to allow more people to experience VR first hand. Experimentation pushing the creative and technical boundaries must continue to ensure that the benefits of ‘true VR’ are realised.

And the healthy collaboration across the industry – from small independent producers through to journalism schools and newspapers and broadcasters – to share learning and techniques must continue, to ensure that news truly embraces the full possibilities of VR.

Hardware

Consumer uptake of headsets remains low. But watching 360 VR video on a smartphone is not immersive, and won’t give viewers the sense of presence offered by ‘true VR’ with a headset and tracking. So at the moment, most VR news is a long way off providing consumers with the intense VR experiences of the kind privileged news editors have seen demonstrated at universities like Stanford.

There are too many platforms: the ‘walled gardens’ around different VR platforms makes it expensive to produce content for a range of devices. There are parallels with the early days of mobile apps, which required different builds for each. Bandwidth is also an issue for viewers consuming this content.

Platforms and device manufacturers need to up their game if they are going to get mainstream audience adoption. This includes improved hardware and common platforms to provide a frictionless user experience, and lower costs for headsets and bandwidth. The news industry needs to work together on this to present a united front when lobbying the tech platforms.

Audiences and Monetisation

Building an audience – and one using headsets for immersive VR rather than 360 – is essential for the long-term monetisation of VR content in news and beyond. And monetising the medium is essential if it is to survive. Digital news has problems enough finding profitability in an ocean of free online content. If VR is to be a part of its long-term strategy, then news organisations’ investments in the technology must at least pay for themselves. Those organisations at the forefront of news VR have been shrewd and enterprising in helping subsidise early content through partnerships with the tech industry, and are developing branded/sponsored content. Branded content is more likely to work for high-end longer form VR content (which will require headset adoption). But this all remains highly experimental – and tech partnerships will not sustain news VR expansion indefinitely.

For that, audiences have to embrace VR in far greater numbers. Yet despite the importance of audiences to the entire industry, there has been very little systematic audience research to date. Early ethnographic research by the BBC suggests we have a long way to go before ‘public service’ content (which includes news) and VR headsets will fit into people’s lives. Discovery on VR platforms is poor, with little effective curation – users need to be able to find content that fits their needs better. The research concludes that the public are confused about VR.

The news industry needs to work harder at managing public expectations of VR. Playing with 360 may be fun for journalists, but the audience needs to be put at the heart of any serious future plans for VR. Audience adoption requires consumer literacy in how to engage with the new technology. Even if part of that education happens through audiences’ consumption of VR content in other areas – sport, gaming – news still has to show them why it is worth engaging with via this new medium.

References

Anderson, Kevin. 2017. Beyond the Article: Frontiers of Editorial and Commercial Innovation. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Aronson-Rath, R., Milward, J., Owen, T., and Pitt, F. 2015. Virtual Reality Journalism. Columbia Journalism School, Tow Center.

Briggs, Asa, and Burke, Peter. 2009. A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet. Polity.

Doyle, P., Gelman, M., and Gill, S. 2016 Viewing the Future? Virtual Reality in Journalism. Knight Foundation.

DPP. 2017a. Survey Report: Consumer Electronics Show. DPP.

DPP. 2017b. Predictions. February. DPP.

Enders Analysis. 2017. 360 and Virtual Reality: A New Angle for Video Entertainment. March. Enders Analysis.

Küng, Lucy. 2015. Innovators in Digital News. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Macquarrie, A., and Steed, A. 2017. Cinematic Virtual Reality: Evaluating the Effect of Display Type on the Viewing Experience for Panoramic Video. IEEE Virtual Reality 2017. discovery.ucl.ac.uk

Peña, Nonny de la, et al. 2010. Immersive Journalism: Immersive Virtual Reality for First Person Experience of News. Presence 19(4) (Aug.), 291–300. https://www.mitpressjournals.org/action/cookieAbsent abs/10.1162/PRES_a_00005

Slater, Mel, and Sanchez-Vives, Maria V. 2016. Enhancing Our Lives with Immersive Virtual Reality. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 19 December.

Wu, Tim. 2016, The Attention Merchants: From the Daily Newspaper to Social Media, How Our Time and Attention is Harvested and Sold. Atlantic Books.

About the Author

Zillah Watson has led the editorial development of virtual reality experimentation at the BBC, with a focus on news. A former current affairs producer and head of editorial standards for BBC Radio 4, she has worked in BBC Research and Development for the last four years to understand the future of content, data, and online curation. She was executive producer of ground-breaking 360 VR films including Inside the Large Hadron Collider 360, The Resistance of Honey, and Fire Rescue 360, all of which have been featured at international film festivals. She produced the first 360 BBC report from the Calais migrant camp in June 2015, and the first newsgathering 360 report with Matthew Price in the immediate aftermath of the Paris terror attacks in November 2015. She was executive producer of the award-winning interactive CGI VR productions The Turning Forest and We Wait.

- For the history of the early radio industry and invention of development of content see Briggs and Burke (2009: 148–56) ↩

- For a recent review of applications of evidence-based beneficial applications of VR, including news, see Slater and Sanches-Vives (2015). ↩

- Jarrard Cole, Executive Producer in Video, Wall Street Journal, interviewed 10 Feb. 2017, in New York. ↩

- Aronson-Rath et al. (2015). Doyle et al. (2016). ↩

- The Tow Center and Knight Foundation reports identified a number of challenges with VR/360 content including storytelling potential, ethics questions, expense of production, monetisation issues, and the fact that potential consumer adoption and the growth of the market were largely unknown. ↩

- The high-end headsets such as the HTC Vive and the Oculus Rift require powerful computers to run them which means that the costs extend beyond the headset. Mobile VR headsets are a fraction of the cost and portable. ↩

- For examples of BBC VR see bbc.co.uk/taster and the 360 playlist on the BBC News YouTube Channel. ↩

- See Slater and Sanches-Vives (2015: 35) for a fuller discussion. Technologists continue to draw a distinction and the Augmented Reality/Virtual Reality (AR/VR) working group of the Consumer Technology Group (CTA) agreed the following definitions at the Consumer Electronics Show in 2017: VR is defined as ‘creating a digital environment that replaces the user’s real world environment’ and 360 video as video that ‘allows the user to look in every direction around them’. It was argued that without fixed reference points and standards the devices, content, tools, and infrastructure for VR and AR could not be developed (Enders Analysis 2017). ↩

- Jenna Pirog, Virtual Reality Editor, New York Times Magazine, interviewed 10 Feb. 2017, in New York. ↩

- Paul Cheung, then Director of Interactives and Digital News Production, Associated Press (AP), interviewed 16 Feb. 2017, in New York. ↩

- Niko Chauls, Head of Emergent Technology, USA Today Network, interviewed 3 Mar. 2017 via Google Hangouts. ↩

- Paul Cheung, interviewed 16 Feb 2017. ↩

- Jessica Lauretti, Head of RYOT, Huffington Post, 14 Feb. 2017, interviewed in New York. ↩

- Varun Shetty, Business and Operations Lead for VR Team, New York Times, 7 Mar. 2017, interviewed by Skype. ↩

- Similar motivations to innovate in digital news (including VR by El País) were described by Kevin Anderson (2017). ↩

- Sebastian Pfotenhauer, Head of Video for Blick Group, interviewed 2 Mar. 2017, in Zurich. ↩

- Martin Heller, Head of Video Innovation, Die Welt, Axel Springer, interviewed 28 Feb. 2017, in Berlin. ↩

- See Syria’s Silence https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZAlywJLDuc0&feature=youtu.be) and Ryad’s Oil https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=txw2Qf3TicQ&feature=youtu.be). ↩

- Maarten Lauwaert, Digital Strategist, VRT News, interviewed 24 Feb. 2017, via Skype. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Mounir Krichane, email correspondence, 9 Mar. 2017. ↩

- The Berliner Morgenpost 360 refugee piece can be viewed at https://interaktiv.morgenpost.de/so-leben-fluechtlinge-in-berlin/ ↩

- Max Boenke, Head of Video, Berliner Morgenpost, interviewed 28 Feb. 2017, in Berlin. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Varun Shetty, interviewed 7 Mar. 2017. ↩

- Providing an accurate figure for headset uptake requires a journalistic investigation in itself. In the hype around VR there is a tendency to exaggerate. ↩

- Varun Shetty, interviewed 7 Mar. 2017 ↩

- Martin Heller, interviewed 28 Feb. 2017. ↩

- Niko Chauls, interviewed 3 Mar. 2017. ↩

- Examples include After Solitary (Emblematic and PBS Frontline) which uses photogrammetry and volumetric video capture to tell the story of 39-year-old Kenny Moore, a recently released inmate who spent years in solitary confinement, and Berlin-based company Vragments who created a VR app to show Stasi interrogation techniques with Deutschlandradio Kultur http://blogs.deutschlandradiokultur.de/stasiverhoer/) and are developing Fader – a VR production tool for news. ↩

- The modelling in Figure 4 is based on a range of historic adoption data to understand future growth scenarios. It attempts to illustrate a best-guess ‘ceiling case’, where the most disruptive credible market scenario occurs, to test how large the market could conceivably become, and then layers in more realistic scenarios to demonstrate more likely uptake. Some of the data is fragile as it was necessary to rely on various proxies. ↩

- Varun Shetty, interviewed 7 Mar. 2017. ↩

- Harvest of Change, created by the Des Moines Register (one of 92 papers under the Gannett owned USA Today Network brand) in 2014, explored the state of Iowa agriculture. It received an Edward R. Murrow award. Pioneering in its time, it provides a reminder of how fast technology and content has evolved since 2014. It can be viewed at https://eu.desmoinesregister.com/ ↩

- Niko Chauls, interviewed 3 Mar. 2017. ↩