Executive Summary

In this report, we examine how public service media in six European countries (Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and the United Kingdom) deliver news via social media at a time when news use is increasingly driven by referrals or consumed off-site on various platforms. The analysis is based on 14 interviews conducted between November 2017 and January 2018, primarily with senior editors and managers for news, or social media for news specifically. We complement the interviews with various analyses of how public service media perform on social media. We analyse public service media’s different social media strategies, how they organise their work, and how they adapt tactically to changes in ranking algorithms and products. The social media platforms of our focus are Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Download the full report here.

We show that:

- Public service media observe some tensions between their strategic priorities, remit, and organisational imperatives and those of commercial platform companies. But they also see social media as an important opportunity for increasing their reach, especially amongst young people and other hard-to-reach audiences.

- All public service media organisations in our sample have established dedicated social media teams to pursue these opportunities, and to develop strategies and tactics for dealing with social media as they develop.

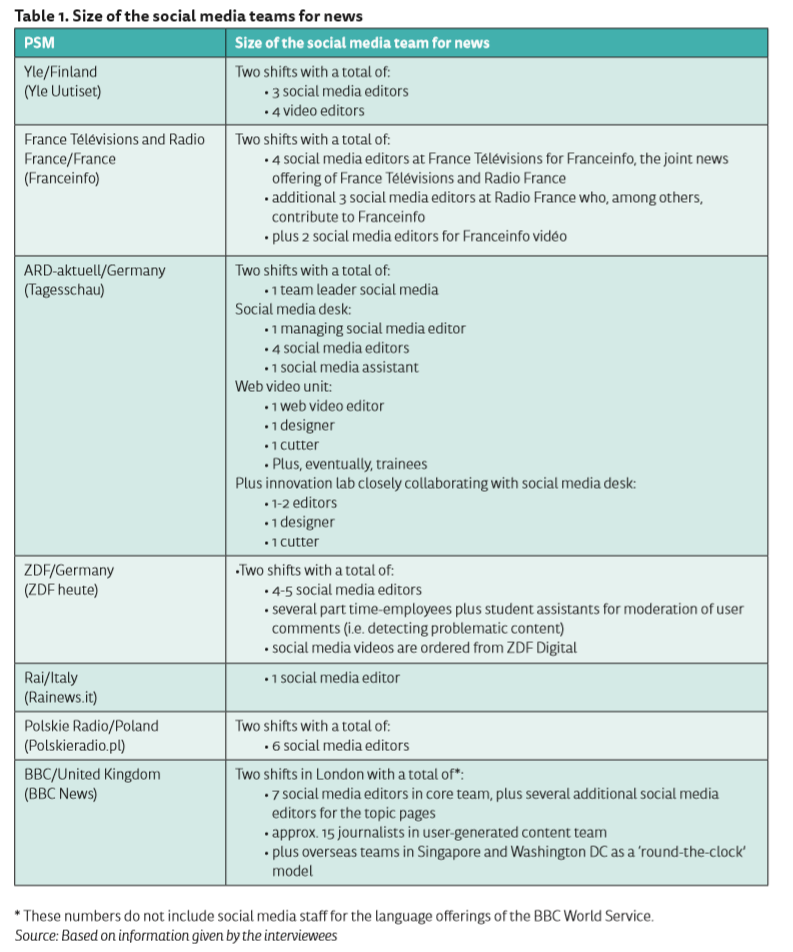

- The size of the teams varies significantly, but social media teams are in all cases only a very small proportion of the organisations’ newsroom(s). This indicates that the resources invested are still in most cases limited (compared to what is invested in for example broadcast activities).

- While many public service media organisations have initially operated a large number of news accounts on various social media platform, they are now trying to consolidate their social media news distribution by reducing the number of accounts, mainly to focus resources and thus serve users better.

- We identified three main aims for public service media to distribute their news on social media: generating referrals to their own websites, reaching younger and hard-to-reach audiences off-site with native content, and, at least for some, user participation.

- How public service media pursue these goals depend on their main strategic focus. Some pursue an on-site strategy primarily aimed at using social media to drive referrals to their own websites. Others pursue an off-site strategy primarily aimed at reaching younger and hard-to-reach-audiences directly on various social media platforms with native content.

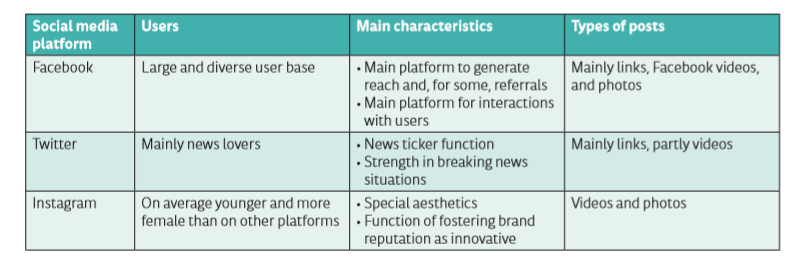

- Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram are seen as the most important social media platforms by our interviewees – and each is seen as offering distinct opportunities and challenges. Facebook offers wide reach to a large and diverse user base. Twitter is used primarily to target a smaller audience of news lovers and as a form of ‘news ticker’, especially important during breaking news events. Instagram is seen as a platform that can help public service media reach younger and female audiences with visual and video content with a different aesthetic from what is on offer elsewhere. Also, some interviewees hope to boost the reputation of their organisation as innovative through their use of Instagram.

- The public service media in our sample pay attention to analytics and metrics. However, they all aim to use them tactically to inform day-to-day decisions and optimise postings, not to determine editorial priorities or dictate long-term strategy.

- All our interviewees stress that they monitor social media’s constant evolution closely in terms of changes to ranking algorithms and the development of new products. But they also underline that they try to maintain focus on their own overall strategy and not let their operations be dictated by changes implemented by platform companies.

- In practice, while there are clear differences between public service media that pursue on-site strategies and those that pursue off-site strategies (as well as in levels of investment in social media), tactically, social media teams in different public service media often work in relatively similar ways. This is largely because they respond to similar incentives from platforms and try to imitate what they see as best practice elsewhere.

Introduction

The move towards a more digital, mobile, and social media environment presents news organisations with challenges and pressure to keep up with audiences’ changing media use. People increasingly use search engines, social media, and other platform products and services as their primary means of finding and accessing news online (Newman et al. 2017). This move to distributed discovery (where news is found via third-party platforms but accessed on publishers own sites) and distributed content (where news is both found and accessed on third-party platforms) presents news media with new opportunities and challenges (Nielsen and Ganter 2017).

In this report, we analyse how different public service media organisations from across Europe handle these opportunities and challenges as they use social media for news distribution. With different editorial priorities and funding models, public service media face the rise of social media from a different starting point than the private sector legacy media and digital-born media we have analysed elsewhere (Cornia et al. 2016, 2017; Nicholls et al. 2016, 2017). On the basis of 14 interviews conducted between November 2017 and January 2018, primarily with senior editors and managers for news, or social media for news specifically, we analyse how social media news distribution is organised in different public service media, what their editorial strategies are, and how they adapt tactically to changes in ranking algorithms and products. The interviews are complemented by various analyses of the performance of the public service media on social media. The social media platforms of our focus are Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. This allows us to compare the distinct functions they have for public service media and the different target groups they try to reach through them. (Public service media often also use other platforms, like YouTube, SnapChat, and others that we do not cover here.) The countries covered are Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and the United Kingdom. Together they represent a range of different European media systems, levels of technological development, and public service media traditions.

One might expect that public service media and social media are a perfect fit as the platforms can help to extend reach and especially can help reach younger and other hard-to-reach audiences, and because public service media due to their funding model do not compete with social media commercially the way private sector media do. However, our findings show that the relationship is more complicated as many interviewees describe a tension between public service values and the values and operations of commercial platform companies. We found two different main strategies used by the public service media organisations. Some pursue an on-site strategy primarily aimed at securing social media referrals to drive users to their own news websites. Others pursue an off-site strategy that primarily aims at reaching younger and hard-to-reach-audiences directly on the social media platforms with native content. Despite these different overall strategies, the day-to-day social media tactics deployed by different public service media are surprisingly similar, because they are oriented towards adapting to the specific content formats, ecosystems, and forms of algorithmic filtering defined and evolved by the same set of platforms. Different public service media with different strategies for social media are thus influenced by what some researchers have called ‘isomorphism through algorithms’ (Caplan and boyd 2018), where platform companies shape other organisations’ behaviour in part through technical processes that structure interactions with their large user base, but also by conferring value and legitimacy on certain ways of using their products and services (see also Nielsen and Ganter 2017).

The organisations we cover are Yle (Finland), France Télévisions and Radio France (France), ARD and ZDF (Germany), Rai (Italy), Polskie Radio (Poland), and the BBC (United Kingdom). We focus on their main national news offers, not regional news. In the case of BBC News, we focus on the UK accounts if there are different accounts for the UK and the World Service.1 Four interviews for this report were conducted in person, but most were via Skype or by telephone. We tried to interview one person responsible specifically for news on social media and one for (online) news more generally per organisation, but were dependent on access. For a complete list of interviewees see the appendix. Our purpose was not to evaluate the public service media organisations individually but to better understand how they think about and approach social media.

The report builds on two previous reports we published in 2016 and 2017 about the same public service media organisations and countries. In Public Service News and Digital Media (Sehl et al. 2016) we offered a more extensive analysis of how public service media organisations see their wider challenges in a changing media environment and how a range of external factors, including political ones, influence their ability to successfully deliver public service news online.2 In Developing Digital News in Public Service Media (Sehl et al. 2017) we focused on how the organisations respond to these challenges and changes and develop new projects and products for digital news.

This report is structured as follows. First, we analyse how the public service media in our sample are organised for news distribution on social media in terms of teams and accounts. Then we explore how they concretely approach social media news distribution. We pay attention to their overall strategic aims, how they use different platforms and content for different target groups, editorial analytics to inform content decisions, and which roles the social media platforms’ algorithms play for their tactics. Finally, we summarise the findings in the conclusion.

1 Organisational Structure for Social Media News Distribution

As social media have become increasingly important for news distribution (Newman et al. 2017) a new job profile has been created: the social media editor, a person who takes care of an organisation’s social media accounts and its strategy for them. This chapter will first focus on why and how the public service media in the sample have introduced special social media teams (section 1.1). In the second part it discusses how they organise their accounts for news distribution (section 1.2).

1.1 Special Social Media Teams

All public service media organisations in our sample have specialised staff for news distribution on social media. At first, some public service media organisations tried to delegate this work to individual journalists to do on top of their normal tasks. But they quickly realised that it needs specialised teams in order that enough attention is paid to social media day to day. For example, Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, the joint news website of France Télévisions and Radio France, remembers:

In fact, when we created Francetvinfo [a previous news website of France Télévisions only], we created it with a very young, very digital [team]; everyone had very active Twitter accounts, [and] we said ‘we don’t need a community manager […] every journalist will do the community management of their content and that will be enough’. And then, as time went on, […] we realised that the journalists didn’t have the time to do it well, […] we needed the visibility that a community manager would give us.3

Sonja Schünemann, head of social media news at German ZDF, also stresses that time to think about strategies and adapt content to different platforms is limited when the job is an extra task for the normal team:

There was no-one who had the time to think: How does the algorithm of Facebook work? What do I need to do so that my posts are seen by the young people who are our target audience? […] If you have to fill a website or a TV news bulletin at the same time, this is the first thing to go.4

Despite having a common organisational structure, with specialised staff for social media, the different public service media organisations have wide variations in the size of these teams. They also vary in the size and organisational structure of their newsrooms. The BBC and the Finnish Yle especially have largely integrated newsrooms. In the other countries news production is still organised around platforms with, in some cases, such as German ARD and ZDF, a certain level of collaboration (Sehl et al. 2016). Within this context, table 1 gives an overview of the size of the social media teams and the different functions within them. It shows that the Italian Rainews.it has just one social media editor, while there are as many as 13-14 people at ARD-aktuell, including a social media desk, web video unit, and innovation lab. However, it needs to be kept in mind that Rai is characterised by strongly fragmented newsrooms and social media accounts (see section 1.2) and many of those have their own social media editor. Furthermore, the news division at Rai is currently in a transient situation, which has slowed down various news projects.5 The analysis of the interviews shows that this has also influenced its social media work for news. Nevertheless, it is also clear that the social media teams in all cases amount to only a very small proportion of the organisations’ newsroom(s).

At all public service media organisations, social media output are covered in shifts from the early morning until around midnight. After that, some organisations rely on pre-programmed content, and at others, the general news editor can take over social media in important breaking news situations. Only the BBC has staff in place to operate the accounts 24/7, though not all based in the United Kingdom – there are teams in Singapore and Washington DC.

1.2 Consolidation of News Accounts

All public service news organisations in our sample operate a main news account that carries the name of their main news website. Apart from that, most organisations are currently working on reducing their number of social media accounts on the different platforms. However, what constitutes the right amount of accounts is seen differently.

The main argument from those who are reducing the number of accounts is that they want to focus their resources in order to serve their audience best. James Montgomery, director digital development, BBC News, says:

I think we’re trying to get to a place where if we have a social presence we want it to be well tended and well looked after so that it creates a really good user experience that reflects well on the BBC, that engages people. […] Part of that, you know, is that we don’t want to waste our time on inadequately maintaining social accounts which aren’t achieving anything. That’s a waste of our resources and licence fee payer money.6

Similar arguments are heard at Yle and the ZDF. Historically, the reason for having a large number of accounts, adds Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC News, has usually been

internal structures and politics [at the BBC], rather than the audiences that we were seeking to serve, so what we are trying to do is reorganise those accounts around the interests of our audience, and so we’re looking to see how we can merge pages, how we can offset accounts.7

Fiona Campbell, controller mobile and online, BBC News, explains that the BBC therefore built a number of topic pages around the main BBC News account in 2016, such as BBC Entertainment News, BBC Lifestyle and Health News, and BBC Family and Education News. She highlights that an additional reason is to be in dialogue with the audience, which is rather difficult at a large flagship news account:

The main news account is too big. […] You can’t have a meaningful relationship with 40 million people. […] But those topic pages are as much about building community and value; the point of these topic pages, in the first instance, is not to get them back onto the main site. It’s more trying to prove value to them of our content. Also, they give us ideas.8

Similarly, this is the strategy at German ZDF, which is in a consolidation and concentration phase with its social media accounts at the moment, as Elmar Theveßen, deputy editor-in-chief, ZDF, explains. This reduction of accounts is based on analysis of data on audience engagement and reach:

What is our growth rate? Is there something happening or not? Maybe because colleagues do not have the capacities to enter dialogue. Then it is better to bundle the activities and be more decisive this way.9

But he also makes clear that when accounts work well or follow different purposes, they will be maintained.10

Another aspect for centralisation, mentioned by Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau, is brand building. He explains that it was a very strategic decision to build up one strong brand on social media with the same name as the flagship news bulletin (and the website).11

On the other side, at the public service media organisations in France and Italy, although some consolidation efforts exist there as well, a higher number of social media accounts is seen as less problematic. Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, argues that all brands should exist on social media as ‘it is better to have connection with the faces of the TV [most popular journalists] and [with the] strong brands of the TV news offering’.12 Also they operate two main news accounts: Franceinfo as a general news account and Franceinfo vidéo for more background videos (see figure 1). While the first account is operated by the social media team of Franceinfo, the latter is operated by social media editors from TV. In this sense, it reflects internal organisational structures, as mentioned above by Mark Frankel from the BBC.

Figure 1. While most public service media organisations try to consolidate their news accounts, internal structures sometimes stand against it. For example, Franceinfo is operating separate accounts for news in general and news videos on Facebook.

Source: Screenshot 15.02.2018

At the Italian Rai, Antonella Di Lazzaro, deputy director, digital division, Rai, states that the whole organisation is currently reshaping its social media strategy. This process includes two steps: reducing the number of accounts and fostering coordination between the different accounts, especially for major events. However, the reduction of accounts, including areas like news, entertainment, different TV programmes and channels, etc., happens from a very high level:

Before there were more than a thousand social media profiles at Rai; now there are – or soon will be – around 300/400 profiles. This is aimed at making our communication a little more focused and a little more effective.13

Despite the two slightly different positions on the appropriate number of news accounts, this section has shown that public service media in general try to consolidate their news distribution on social media. In some cases, it is complemented by topic accounts focused on the special interests of targeted audiences, or by channel and bulletin accounts promoting and accompanying the channels and news bulletins, rather than being a news offer themselves. The main arguments for consolidating the news efforts on social media are 1) to focus resources, in order to serve users better, 2) to concentrate on the accounts that perform successfully while merging/integrating the others, and 3) to profit from one strong brand.

2 Editorial Strategies for Social Media News Distribution

The following chapter describes the editorial strategies for social media news distribution that are used by the public service media in our sample.

2.1 Reaching Younger and Hard-to-Reach Audiences

All public service media organisations in our sample have a clear main aim with social media news distribution: to reach younger and hard-to-reach audiences that do not necessarily come to the public service media destinations anymore. In addition to younger age groups, the public service media organisations try to attract other underserved audiences to the news on social media, especially women and people with low income, explains Fiona Campbell, controller mobile and online, BBC News.14 Christiane Krogmann, editor-in-chief of Tagesschau.de, ARD, echoes her views, and explains that 70% of their Tagesschau.de readers are men, mostly with a high formal education, whereas on social media they have a 50–50 split of men and women, so significantly more women are reached via social media rather than through their website.15 Many interviewees argue that because their mission is to serve the entire public, public service media need to be where the public is, even though this is on social media.

While there is consensus regarding the aim of reaching new and hard-to-reach users, there are different strategic approaches to doing so. Some organisations pursue an on-site strategy aimed at bringing traffic to their own websites. Others pursue an off-site strategy aimed at reaching user on social media, often with native content.

Franceinfo and Polskie Radio are both examples of public service media primarily pursuing an on-site strategy. Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, says:

There are a lot of discussions about what we give to GAFA [i.e Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon] when we publish content on platforms. […] We give them content produced by us, and that gives rise to a lot of thinking among TV journalists in particular, who say to themselves, ‘But aren’t we shooting ourselves in the foot and doing what will lead to our disappearance?’. […] What we are trying to argue is that it is not a matter of giving anything to GAFA, it is [rather] a matter of going to find a wide audience and bringing this audience back to us. Telling them: ‘We have quality info, come to see us at home.’16

Similarly, the main goal of Piotr Chęciński, editor-in-chief of Polskieradio.pl, Polskie Radio, is to bring traffic to its own destination site. Hand in hand with this, content is, in most cases, not produced for social media specifically but just linked back:

In more than 80% of examples, it’s always linked with the news that is published on the website Polskieradio.pl. […] The first and the main goal is to bring more traffic to the website because many social media like, for example, Twitter are allowing us to inform in a very limited way.17

In contrast, the German ZDF is a clear case of a public service media organisation primarily focused on an off-site strategy. Elmar Theveßen, deputy editor-in-chief, is convinced that news on social media has to be native as this is what the users expect:

If we only posted links or promoted our website or our TV programme, it wouldn’t work, I think. Then the users would say, ‘I don’t need this at all, because I want to inform myself in this environment.’18

The two different strategies are illustrated in figure 2. The two strategies are not necessarily a strict binary choice, as an organisation can, with enough resources, invest in social media for a wide variety of purposes, or use different strategies for different target audiences. But there are clear trade-offs and some organisations position themselves clearly as focused on one or the other strategy, while others try to pursue both goals at the same time.

Figure 2. On-site and off-site strategies for public service news on social media (examples)

Source: Based on information given by the interviewees

Beyond a focus on either building on-site audiences through social media referrals (distributed discovery) or off-site audiences through native content published directly on social media (distributed content), some public service media, in addition, aim to use social media to foster a dialogue with their users. Especially the BBC in the UK and ARD and ZDF in Germany highlight this as an important priority for them as public service media. At the BBC, Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC News, motivates every social media editor in his team not only to distribute news, but also to engage in discussion with the users and to listen to what they are interested in through comments and various data tools – as well as to potentially profit from user-generated content.

One of the hallmarks of the BBC, and its sort of values, has been not just that we’re there to inform and to entertain, but that we’re also there to give our audiences a degree of participation in that process, to listen and involve and communicate with our audiences, and to be transparent with our audiences both about what we know and what we don’t know and how we can benefit from their inclusivity and their interactivity with our news journalists.19

A similar perspective is adopted by Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau. However, he also mentions, like other interviewees, the challenges that accompany this approach.

A good, constructive dialogue with our users is very important to us. However, this is very difficult, because we get 12,000 to 15,000 comments per day on the different platforms.20

In this respect, this section has shown that social media is not only a platform for news distribution for public service media in order to inform younger and hard-to-reach audiences, through either an on-site or an off-site strategy, but for some public service media also a platform for contact and exchange with their users, blurring traditional boundaries between senders and receivers (see, for example, Loosen and Schmidt 2012). While this requires significant resources, they stress that they see this as a task, especially for public service media, that should allow for participation and that needs to involve the whole of society.

2.2 Different Platforms and Content for Different Target Groups

This section discusses how the public service media organisations in the sample approach different social media platforms and which target groups they have in mind in each case. The section focuses on the main platforms – Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram – that they all cover. It is important to say that some of them cover more platforms, such as YouTube or Snapchat, but with minor focus.

The most important social media platform in terms of reach for all public service media organisations in the sample is Facebook, due to its large and diverse user base. The simple reason is that it attracts most users of all kinds. Sonja Schünemann, head of social media news, ZDF, says:

Facebook is still the best social media platform for reach […] because many people in Germany are using Facebook, young and old. […] We have more interactions on Facebook, more video views, and more visits to our website.21

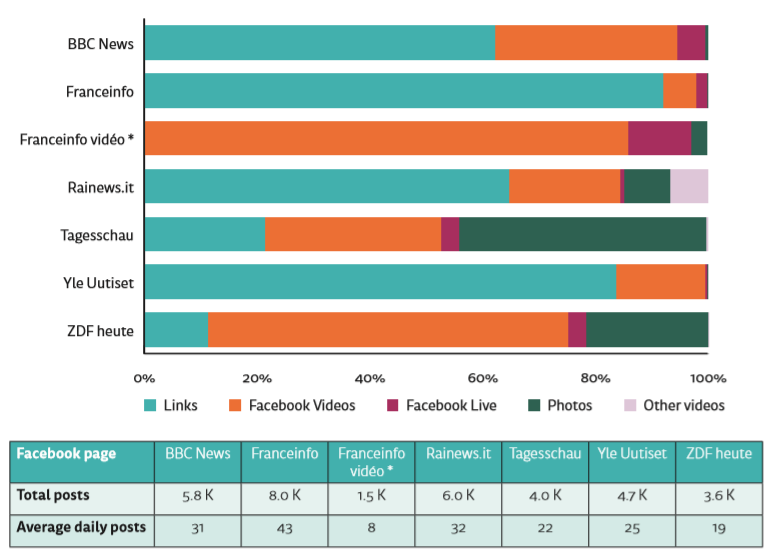

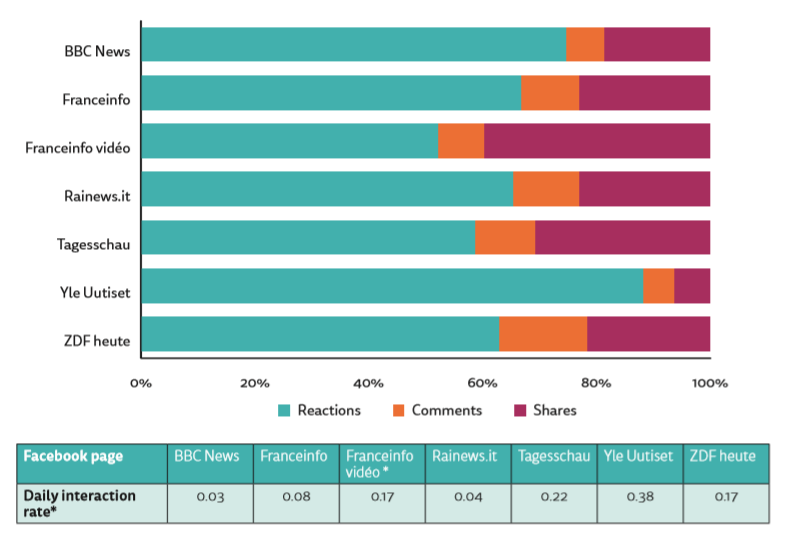

Figure 3. Public service media news distribution on Facebook (01.05.2017–31.10.2017)

* Franceinfo vidéo is a separate account just for video.

Source: Data analysis based on data from CrowdTangle. Data is based on global audience. The Facebook account of

Polskieradio.pl is not included in the analysis as the data is not available from CrowdTangle.

With regard to the content published on Facebook, interviewees highlight the variety of formats that Facebook allows, including links, videos, and photos. Figure 3 gives an overview of how the different public service media organisations are using Facebook for news distribution, how many daily posts they create on average, and what types of posts they focus on. The difference between the on-site strategy of Franceinfo (92% links back to their own site) and the off-site strategy of ZDF (just 11 percent links back to their own site) is clear.

The table shows that all public service media organisations in our sample use Facebook to distribute links to their own news websites. It is obvious that this is especially true for those news outlets that have the clear strategy of bringing traffic to their news websites, like Franceinfo, Yle Uutiset, or Rainews (see section 2.1). A second look shows that the two German public service media organisations ARD and ZDF distribute far fewer links and focus more on photos and videos. Sonja Schünemann, ZDF, argues that it is quite logical that ZDF as a TV organisation does video online.22 Although not explicitly mentioned by the interviewees, this finding can also be explained in another way. In Germany, public service media have more legal constraints over what they are allowed to do online than in many other countries, and the commercial publishers want them to focus on video in order to avoid influence on their business (see, for example, Weberling 2011). Furthermore, the average number of articles shows that they post fewer articles on Facebook than on their websites. For example, Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau, ARD, says ARD-aktuell publishes between 30 and 40 news articles a day on its website Tagesschau.de.23 On Facebook, figure 3 shows that it generates just over 20 daily posts.

However, the BBC and to some degree the Italian Rai also focus on video. Franceinfo has two different accounts for news in general and video, which as explained in section 1.2 is more due to internal organisational factors than the needs of users. Facebook Live is rarely used by most public service media organisations, but a couple of interviewees mentioned that they plan to use it more often. Antonella Di Lazzaro, deputy director, digital division, Rai, describes its potential as a format that allows for the participation of users:

Facebook is instead the place [where you can go] a little more in-depth; it is the place where you can actually have question-and-answer sessions with users through the Facebook Live tool, and then take care of users’ questions, answer them, and create an arena for favouring users’ involvement and responses.24

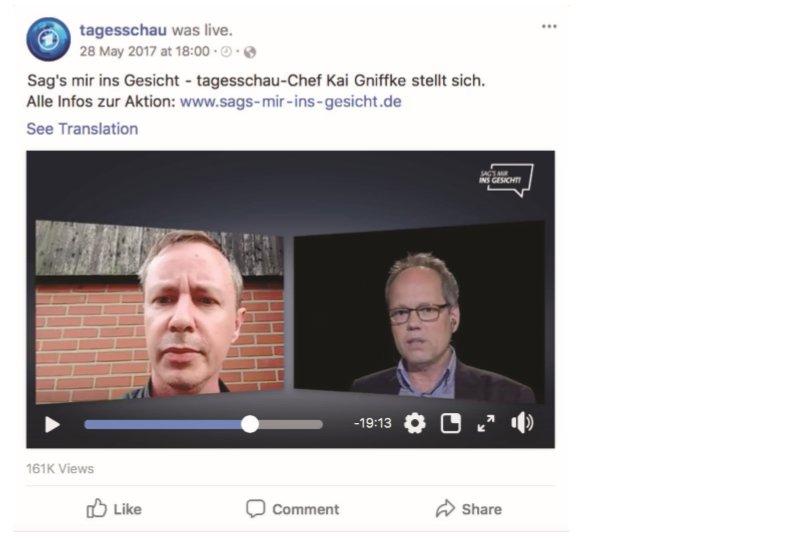

Facebook has also been used for this purpose by, for example, ARD-aktuell. To have a direct face-to-face dialogue with users, instead of anonymous hate speech, was the aim of the format ‘Sag’s mir ins Gesicht’ (Tell me to my Face). Here, senior editors and presenters discussed with users their criticism of reporting, for example on how ARD reported on the party AfD. The dialogue was on Skype but streamed on Facebook, Tagesschau.de, Tagesschau24, YouTube and Periscope (see figure 4).

Concerning topics on Facebook, the interviewees mention that this differs from, for example, Twitter by covering hard news like politics or economics, but also favours softer news or looks for an aspect in the news that makes it discussable or shareable on social media (see section 2.3).

Figure 4. Facebook Live can be used as a tool to create a dialogue with the users; here, first editor-in-chief of ARD-aktuell, Dr Kai Gniffke, discusses reporting with a user.

Source: Screenshot 22.03.2018

Twitter is seen as distinct from Facebook in its function and target group. It is described as a ‘news ticker’.25 Although the public service media organisations report that their reach with Twitter is marginal, they highlight the strength of Twitter for informing highly news-interested users and its speed in breaking news situations. Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC News, says:

I think Twitter has a big role to play in a locus on real-time news and allowing the BBC to have a clear voice within that, particularly around the developing story, to be able to say to audiences, we’ve got something that you’re going to want to follow here, and that we are your trusted guide through that process, but I was also conscious that the benefit to the audience beyond that breaking news and real-time news environment is more limited, in the sense that most of our audiences are not on Twitter.26

In contrast to Facebook and other social media platforms, many public service media organisations also post all the news they publish on their websites on Twitter, as they assume the users appreciate it. To keep the workload for the more niche platforms low, some of them, like German ARD or Finish Yle, use a bot for this purpose.

Franceinfo gives a unique reason for being on Twitter. Mohamed Belmaaza, senior product and editorial analyst at Franceinfo.fr, says that they use Twitter to help their position on Apple News. He says:

On Twitter, […] we had previously stopped investing in it because it generates very little traffic. Then Apple News arrived and today Twitter is the lever [to prioritise our content on] Apple News. Being on it, we know that it generates very little traffic per week or month, but for us it generates a lot of traffic indirectly. So, we have to be there, but in a way that adapts to how people consume information on Twitter, using impactful visuals (quotation cards, images, gifs, native videos…) that instantaneously deliver important information to our readers on the platform, without necessarily having to click on the story link. Data show that the more a story gets retweeted, the higher the chances are to be featured on Apple News.27

Figure 5. Interviewees see Twitter as strong for breaking news situations. Below, the daily interaction rate* on the Twitter account Tagesschau of German ARD is especially high on 25 September 2017, one day after the German federal election.

* The daily interaction rate is calculated by CrowdTangle by averaging the number of interactions for all of the account’s posts in the specified time frame (daily), then dividing that by the number of followers/fans.

Source: CrowdTangle. Data is based on global audience.

It is not clear how exactly Twitter activity might in fact influence placement on Apple News, but Belmaaza’s reasoning reflects how public service media (like other news organisations) are frequently trying to second-guess how exactly often opaque platform products and services actually work (Nielsen and Ganter 2017).

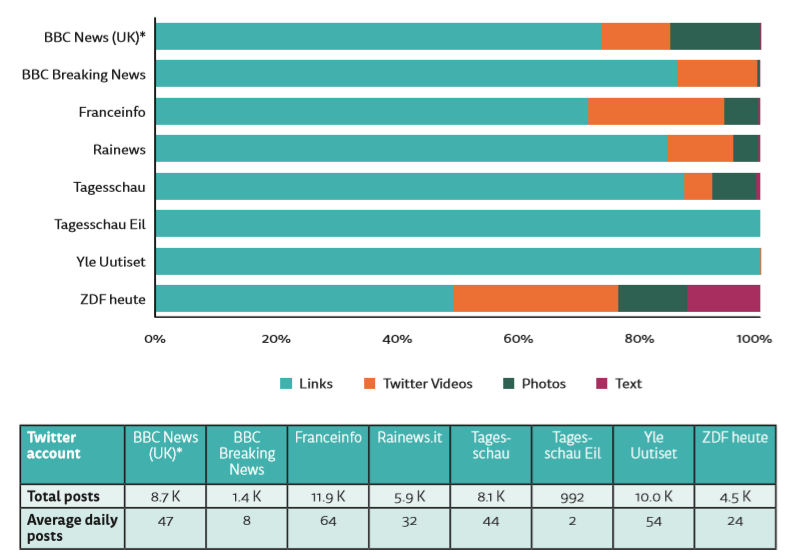

Figure 6 reflects the general focus on links. Twitter is used to convey very short news updates on-site through headlines and snippets (to be relevant in breaking news situations and reach the specific audience found on Twitter), but there is little emphasis on tailored, native content produced specifically for Twitter, as this platform has a smaller user base than for example Facebook and is a less significant driver of reach and referrals.

ZDF, as well as Franceinfo, is an outlier in the sense that they both also post a significant amount of Twitter videos. For ZDF, this is in line with their general emphasis on an off-site strategy, for Franceinfo, it shows how public service media sometimes pursue different strategies for different social media as explained by Mohamed Belmaaza from Franceinfo.fr above. Sonja Schünemann explains that the videos ZDF posts on Twitter are different videos than on Facebook:

We have videos with our correspondents. When we uploaded those on Facebook, they were not successful. We have learned that users on Facebook don’t want to see a talking head who is not prominent. But on Twitter this is successful because it is easy to get information about a location where the users might not know anyone to ask.28

Figure 6. Public service media news distribution on Twitter (01.05.2017–31.10.2017)

* The data is provided for the Twitter account BBC News (UK). In addition to this, the BBC operates an account BBC News (World).

Source: Data analysis based on data from CrowdTangle. Data is based on global audience. The Twitter account of Polskieradio.pl is not included in the analysis as the data is not available from CrowdTangle.

All the public service media organisations in the sample have also started to distribute news on Instagram. They describe Instagram as clearly distinct from Facebook and Twitter. The two characteristics many of the interviewees mention related to Instagram are its special aesthetics, which focus on pictures and video moments, and that Instagram allows them to reach younger target groups than on the other social media platforms. Sonja Schünemann, ZDF, says:

It’s great that the users we reach there are even a decade younger than the ones we reach on Facebook – which is a sensation for the ZDF. The TV viewers are on average 63, our core Facebook users between 25 and 34, and our users on Instagram even younger.29

Patrick Weinhold, ARD, adds that for ARD-aktuell there are more female users on Instagram than on other platforms and they have different specific interests, such as environmental topics and social justice in particular.30

With the young target group, Instagram is also named as a channel that can help project a reputation as an innovative brand, as Timo Kämäräinen, executive online producer, news and current affairs, Yle, mentions: ‘Instagram is […] about naming our brand, and making a good, colourful impression.’ 31 Although he says that it is possible now with Instagram stories to drive some traffic, it is not the main aim and it is not explicitly mentioned by other interviewees. As we have argued elsewhere, news organisations sometimes pursue digital initiatives as much for the indirect benefits (like building an image as an innovator) as for the direct benefits (such as reaching new audiences) (Cornia et al 2017).

Figure 7. Instagram is used by public service media to attract an especially young audience with aesthetic pictures and videos.

Source: Screenshot 27.01.2018

Sonja Schünemann, ZDF, shares an experience her team has had on Instagram. In the beginning they were posting subtitled video, but the audience data showed them that this approach was not successful. She says:

We completely changed the strategy and started from scratch. Now we try to create video moments. We just take one news-moment in motion, that stands on its own and is internationally comprehensible. We provide information and context in the Instagram-caption, but allow the user to purely ‘feel the moment’.32

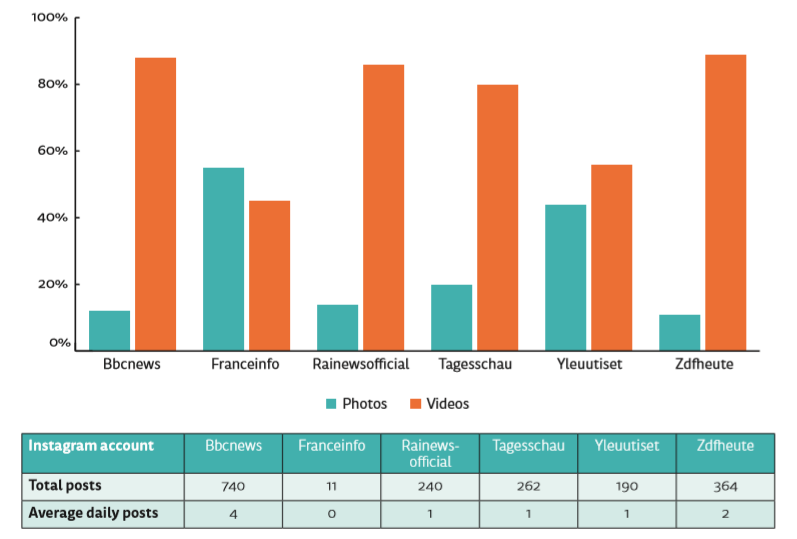

Figure 8 gives an overview of the Instagram activities of the public service media organisations in our sample for news. It shows that videos are in almost all cases preferred over photos, but the mix varies from organisation to organisation. With the exception of the BBC, which is operating only one account for UK and World, all others do not publish more than a maximum of two posts on average per day, much less than on other platforms. This might be due to the fact that Instagram requires, as explained by the interviewees, a special approach. Not all topics are suitable for the platform and it often requires extra work. Across both public service media and private sector media, people we have interviewed for our research highlight that the need to tailor content and tactics for individual platforms increases the cost, and that the return on investment can be unclear, especially for platforms with a smaller user base, a lesser emphasis on news, and/or where data to evaluate effects is hard to obtain (see Cornia et al 2016; Nielsen and Ganter 2017; Sehl et al 2016).

Figure 8. Public service media news distribution on Instagram (01.05.2017–31.10.2017)

Source: Data analysis based on data from CrowdTangle. Data is based on global audience. The Instagram account of Polskieradio.pl is not included in the analysis as the data is not available from CrowdTangle.

In summary, this section has shown that the public service media in our sample have different perceptions and aims with different social media platforms for their news distribution. Consequently, they also have different approaches to them. Almost all of them produce formats specifically for social media, but not in a ‘one size fits all’ approach, as Christiane Krogmann, editor-in-chief of Tagesschau.de, ARD, calls it,33 but they produce distinct formats for the different social media channels appropriate to the different strengths of the described platforms. One exception is Polskie Radio as it does not publish much original material on social media but mostly links back to its website.34

Table 2 summarises what the interviewees have named as the main potential of the different platforms and what the CrowdTangle data analysis has shown as the main post types covered on those platforms. Overall, investment tends to focus on Facebook as it is the largest platform and can help deliver the widest reach, irrespective of whether an organisation pursues an on-site or an off-site strategy. Twitter, Instagram, and other platforms are seen as important for more specific purposes and specific target audiences, but public service media invest much less in these social media platforms.

Table 2. Social media platforms and their characteristics

Source: Based on information given by the interviewees (users and main characteristics) and CrowdTangle analysis (types of posts)

2.3 How Analytics Inform Social Media Tactics

This section discusses what role metrics and analytics play in social media news distribution for public service media. In addition, it analyses what the most important metrics for the interviewees are, and why. Finally, it gives an overview of the position of each public service media organisation in their national news markets regarding audience engagement.

All public service media organisations in our sample report that they increasingly embrace the use of metrics and analytics for news distribution on social media. For example, Antonella Di Lazzaro, deputy director, digital division, Rai, describes how they monitor the user data ‘to understand what types of news and formats satisfy users’ tastes and at which time of the day.’35 While some organisations still have a more rudimentary approach to data, other organisations use available or home-grown technological tools to optimise their posts in real time. (For how media use editorial analytics, see for example, Cherubini and Nielsen 2016.)

Nevertheless, there is agreement from all interviewees that while analytics and metrics can inform their publishing decisions, they are still editorial judgements in the end. Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC News, says:

The dashboards can certainly help to inform you about something that you have been blind to or where you perhaps have been over-emphasising one story and under-emphasising another; so they certainly help, but they’re not a panacea.36

Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, echoes many other interviewees, saying that while editorial analytics can help to optimise posts, public service media should not focus only on the audience data, especially when they select topics, as they have a certain public service mission:

We are a public service news media, so there is sometimes important news that we publish even if we know that it’s not what will necessarily work best [in terms of reach or engagement].37

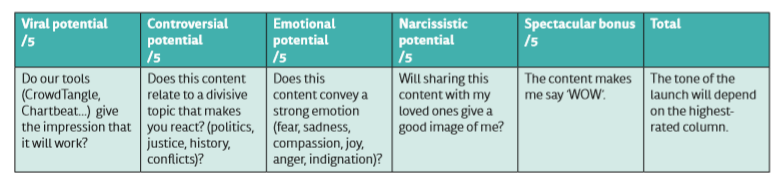

However, Thibaud Vuitton says that during peak hours they carefully select posts according to criteria that Franceinfo defines as the viral, controversial, emotional, and narcissistic potential of a topic as well as what they call a ‘spectacular bonus’ (see table 3). The category ‘viral potential’ shows that they use editorial analytics tools to predict the performance of a post. In each category, the social media editors can assign up to five points to calculate a total value. The framing of the post, the grid suggests, should then depend on the highest-rated column.

Table 3. Evaluation grid to select topics for social media news distribution at Franceinfo.fr during peak hours

Source: Table provided by Franceinfo.fr, translated from the French language by the authors of the report

When asked which metrics are most important to them, the answers of interviewees varied to some degree, usually in line with their slightly different aims for social media news distribution. Those who aim to drive traffic to their news websites (see section 2.1) answered more frequently that they pay most attention to reach. For example, Timo Kämäräinen, executive online producer, news and current affairs, Yle, says:

The main metrics for us are the link clicks to our site from Facebook. Of course, we pull other numbers, as well. For example, engagement. It’s obvious that you cannot reach [people] if you don’t have any engagement and so on.38

In contrast to this is the position of ARD-aktuell. In line with its more native content strategy discussed earlier, it pays most attention to interactions (i.e. reactions, shares, and comments), the growth of friends and followers, and only then the reach, as Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau, ARD, explains. The reason behind it is that it wants users to engage with the content and to reach new target groups:

We also know that reach is something we can influence via the other two factors, interactions and growth. Therefore, it would be wrong to think that reach should be the starting point for thinking about success factors.39

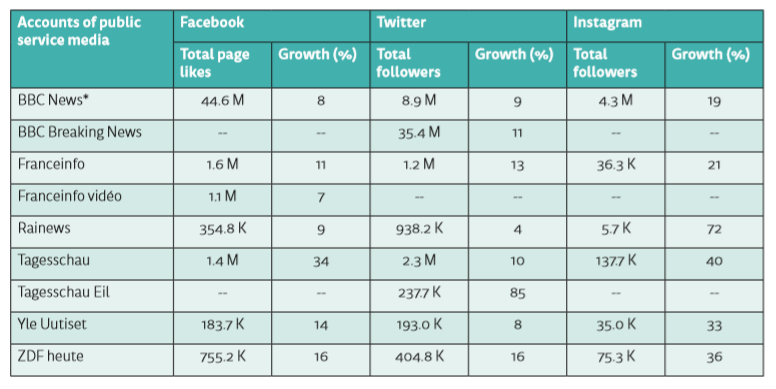

Table 4 gives an overview of the growth of page likes/Facebook and followers/Twitter and Instagram for the news accounts of the public service media organisations. It shows that while they have all grown, the actual growth varies. Indeed, the Tagesschau accounts of German ARD have comparatively high percentages of growth on all three platforms. In general, Instagram shows the highest growth of the three platforms for all public service media. This is probably in large part because of the low base. It is the newest of the three platforms and public service media have only recently started to be present there.

Table 4. Page likes/Facebook and Followers/Twitter and Instagram for news accounts of public service media (Total page likes/followers on 31.10.2017 and growth between 01.05.2017 and 31.10.2017)

* In the case of the general Twitter account, the data is provided for the Twitter account BBC News (UK). In addition to this, the BBC operates an account BBC News (World).

Polskieradio.pl is not included in the analysis as the data is not available from CrowdTangle.

Source: analysis based on data from CrowdTangle (and rounded to full digits for the percentages). Data is based on global audience.

Shares are most important to most interviewees as this is the interaction that gives their content most visibility – or in other words reach. A few say that all interactions are equally important to them. Reactions are usually seen as the least important, especially ‘likes’ which are least interpretable for media organisations. User comments or discussion and interactions between or with users, in general, are explicitly mentioned by just a few public service media organisations.

Figure 9 shows the percentage of the different reactions, comments, and shares on all interactions for Facebook news pages of public service media as well as the daily interaction rate. It shows that, in general, reactions are easier to get for the public service media than shares and especially comments. It doesn’t take much effort for the user to click on a reaction. To share is also only one click but, as some interviewees mention, users often only do it if they identify with the content; that is if the content validates their viewpoint. Finally, commenting has the highest barrier as it requires the users to write a few words, ideally well thought through, on their own, making their personal opinion or information visible.

Figure 9. Interactions by interaction type and daily interaction rate for Facebook news pages of public service media (01.05.2017–31.10.2017)

* The daily interaction rate is calculated by CrowdTangle by averaging the number of interactions for all of the account’s posts in the specified time frame (daily), then dividing that by the number of followers/fans.

Polskieradio.pl is not included in the analysis as the data is not available from CrowdTangle.

Source: analysis based on data from CrowdTangle. Data is based on global audience.

Broadly, the sites that focus on off-site strategies and invest in native content (like ARD, Franceinfo vidéo, and ZDF) see more engagement than those that pursue on-site strategies and mostly post links (like Franceinfo and Rai). But the figures are not clear-cut and should be treated with caution. Because the data is global, the BBC’s strong domestic position is diluted by its broad, international, reach. Similarly, YLE profits from a very strong domestic position and language barriers.

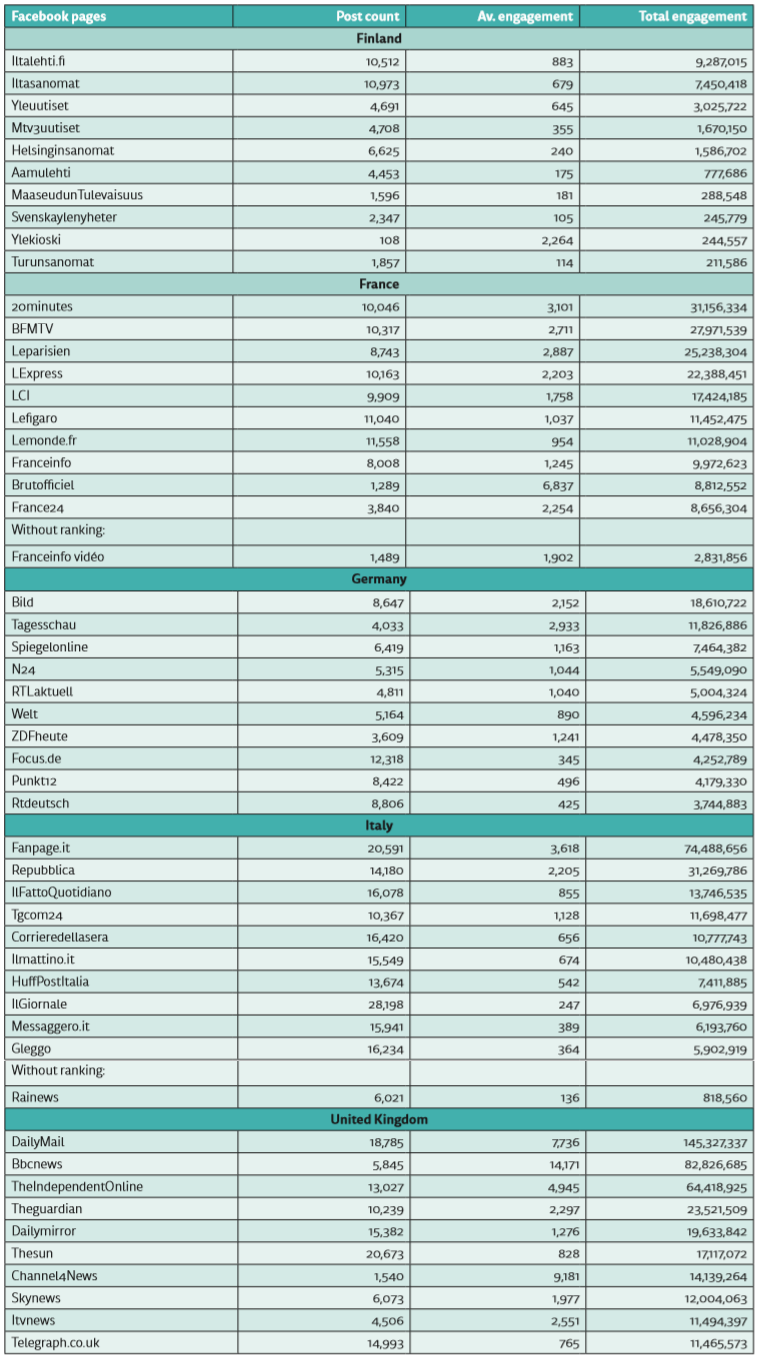

Table 5 shows a ranking of media organisations’ social media news pages in the different national markets according to engagement figures (= sum of reactions, shares, and comments). They show that the position of public service media organisations varies quite a bit, with the BBC, Yle, and also German ARD scoring high in their national markets; the German ZDF and Franceinfo are still in the top ten. There is no ranking for the Italian Rainews as it was not in the top 100 Facebook accounts (general, not only news) in Italy, which was the basis of our analysis. The same is true for Franceinfo vidéo. For Poland, there was no data available for Polskie Radio.

Table 5. Facebook news pages of public service media compared with the top news pages in their countries by post count, average engagement and total engagement (= sum of reactions, shares, and comments), ranking according to total engagement (01.05.2017–31.10.2017)

Source: Analysis based on data from NewsWhip. Data is based on global audience. The baseline in each country was the top 100 Facebook accounts by total engagement. Those were filtered for news pages with the criteria 1) general news, covering relevant topics of the day (and not only specialised news like sports or primarily entertainment), 2) the specific news pages of news organisations (and not their general sites, if separate sites, for example Channel4News and not Channel4), and 3) only pages in the languages of the respective countries and not in foreign languages.

Despite the data available through editorial analytics tools that allow public service media organisations to track their posting performance in real time, some organisations are concerned about how reliant they are on the platforms for data access (Nielsen and Ganter 2017). For example, Mark Frankel, BBC News, says:

We’re reliant on the social companies themselves for that data, and it’s been not entirely reliable. There have been a number of instances where they have over-reported or under-reported things, where the data sets have been revised or incomplete. We are only getting data from Facebook, for example, related to video in that instance. The data that we get around non-video content is still very limited, although we’re working on that.40

In summary, this section has shown that all public service media pay attention to analytics and metrics, but they all state that they use them only to inform their decisions or optimise a post. They are used for tactical purposes, not to determine strategy. All interviewees explain they could generate more reach and more engagements on social media if they posted more ‘soft news’, but that they do not see that as central to their public service remit and thus prioritise other content.

The interview analysis has also shown that, generally, the importance of different metrics for different public service media organisations is usually in line with their aims for social media distribution, as discussed in section 2.1. The importance of reach is mentioned as the primary aim for those who mainly want referrals. Others, having a more native distribution strategy, also pay attention to reach, but even more to interactions and growth. How engaged the audience of public service media is on Facebook for news compared with other news outlets in the respective countries varies quite a lot. Possible influencing factors seem complex, including internal factors (such as organisational priorities or structures) and external factors (such as the market position of competitors, resources available, or legal conditions).

2.4 Observing Platforms’ Algorithm and Product Changes

This section discusses how public service media constantly adapt to changes in platform companies ranking algorithms and products. Over time, decisions taken by companies like Facebook have led to great fluctuations in reach and referrals. According to data from the analytics company Parse.ly, Facebook grew from providing about twenty-five percent of all identifiable external referrals to publishers in 2014 to a high point of more than forty percent in 2016-2017, before changes to the News Feed ranking algorithm and other strategic decisions by the company led to a general decline back to about twenty-five percent of identifiable external referrals at the end of 2017.41 Similarly, social media companies continuously develop new products and services, test them, change them, and sometimes discontinue them. Facebook, for example, has changed its ranking to prioritise ‘reactions’ over ‘likes’ (February 2017), reduced the reach of accounts that post more than fifty times a day (June 2017), and announced it will prioritise local news in the News Feed (January 2018). It has also made design decisions like making the logos of publishes more visible (August 2017) and introduced new products like Facebook Instant Articles (2015), Facebook Live (2016), Facebook Watch (2018) and many more. In each case, public service media, like other media organisations, have to decide on how to respond to these frequently unilateral decision by platform companies that they increasingly rely on for reach and referrals.

Our interviewees see this as a dilemma. On the one hand, they all monitor the platform companies to understand their overall strategy, track changes to ranking algorithms and other technical features, and infer from this short- and long-term consequences for how they can use platforms to reach their target audience. On the other hand, they do not want to play ‘this sort of cat and mouse game with [the platforms] all the time’, as James Montgomery, director digital development, BBC News, puts it.42 Public service media organisations are trying to maintain their strategic autonomy even as they tactically continuously adapt to the rise of platforms and their constant evolution. Elmar Theveßen, deputy editor-in-chief, ZDF, says: ‘Reach is only guaranteed with the established social media platforms at the moment.’43 Public service media thus, like media organisations more broadly, are empowered by social media that can help them reach new and wider audiences, but are also concerned that they are growing more dependent on these platforms. Many see a tension here between short-term opportunities and long-term worries about how to maintain their own strategies and their independence from the platform companies (Nielsen and Ganter 2017).

Many interviewees describe how they observe the platforms’ actions and changes in the algorithms and to find a balance between those requirements and their own interests. Timo Kämäräinen, executive online producer, news and current affairs, Yle, explains:

For example, when Facebook starts to promote more long form videos on its own platform in order to sell more advertising, then we have to consider whether we can play our videos on Facebook, and to what extent, since we have to take care of our own platform.44

Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, recalls that his organisation was hit hard when Facebook decided to abolish ‘the carousel’, a format that combined native video on Facebook with an accompanying article that brought traffic to the organisation’s news website: ‘We used this feature a lot and it worked very well, and overnight it was cut off by Facebook.’45 In the following weeks, according to Mohamed Belmaaza, senior product and editorial analyst at Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, the organisation’s growth of Facebook fans slowed down and it interpreted this as connected with the end of publishing native videos. Therefore it decided to resume publishing 2 to 3 native videos (based on their initial performance on the website) – compared to 5 to 6 per day, previously – in order to profit from the algorithm again: ‘And that’s why we decided that even if video views was not our primary goal, publishing some of our video content directly to Facebook helps us to grow our Facebook fanbase in a fairly important way.’46

Christiane Krogmann, editor-in-chief of Tagesschau.de, ARD, mentions that her organisation is in direct contact with platform companies like Facebook in order to make them aware of news organisations’ needs and positions. However, she also admits that in the end the power relationship is asymmetric and news organisations cannot do much if a platform company decides on a strategy that is to news organisations’ disadvantage.47

Nevertheless, interviewees highlight that they are in a somewhat privileged position being public service media that also have destination sites and do not need to make profits. (However, this only applies to BBC UK, not BBC in general.) James Montgomery, BBC, says:

In general, we are not so dependent on social platforms that we get into a constant panic about it. We try not to react every time there’s a small algorithmic change that tweaks it a bit this way or that … We’re trying to do it for the long term. […] I realise if you’re a small start-up that has no direct traffic and you’re entirely dependent on social distribution to reach your audience, it’s pretty scary if suddenly Facebook creates an Explore page for news publishers, or other changes happen, and you can see huge swings in your audience performance.48

Public service media organisations can also take concrete, tactical steps to pursue their goals on social media, for example brand recognition (which is generally far lower than with direct traffic, see Kalogeropoulos and Newman 2017).

James Montgomery from BBC News says:

[I]t’s really important that when audiences consume the BBC in a third-party environment, they recognise that it is the BBC that they’re seeing. That’s partly wrapped up with the problem of fake news and users being unable to identify journalism by prominence or distinguish between reliable and unreliable information. From a purely BBC perspective, if people can’t recognise that it’s the BBC they’re consuming, then it weakens our relationship with that audience in ways which are, in the long term, very unhelpful, around public support for the licence fee.49

Christiane Krogmann from the ARD is just one of several interviewees who underline how a multiplatform approach is central to maintaining strategic autonomy, including investing in an organisation’s own platforms as well as in different social media platforms, to be less dependent on just one company:

In an ideal world, we would be present on all platforms to a similar extent. But due to limited resources, we need to prioritise where we want to be. And this prioritising, of course, is influenced by [the balance of our own and the platform interests].50

Figure 10. Correct brand attribution on social media is one concern of public service media; here, ZDF heute works with two logos.

Source: Screenshot 21.03.2018

To conclude, this section has shown that all public service media follow the strategies of the platform companies, and ongoing changes in their algorithms and products, very closely. They also continually adapt to these changes. Many of these tactical responses are very similar, across public service media with otherwise very different strategies and priorities, because they are responding to the same changes in algorithms and products, an example of what some academics call ‘isomorphism through algorithms’ (Caplan and boyd 2018), and because social media teams imitate what they see as best practice from elsewhere. However, many of the interviewees highlight the importance for them by balancing this with their long-term strategies, and argue that as public service media with a special remit and funding, they can maintain a greater independence from platform companies than some private sector media, who may need the reach and revenue potential that platforms offer more urgently. Strategies to retain their independence are diversifying in terms of platforms and trying to build a loyal audience that comes to their own destination sites so that they can be more independent from the algorithms.

Conclusion

In this report, we have analysed how different public service media organisations across Europe use social media for news distribution.

On the basis of interviews conducted with senior editors and managers, we find that all public service media organisations in our sample invest in social media to reach wider audiences online, especially younger and other hard-to-reach audiences. Because of their funding structure, public service media do not compete directly with social media for advertising, but they still see tensions between their public service remit and the priorities of commercial platform companies.

We have identified two main strategic approaches to social media amongst public service media. Some pursue an on-site strategy and primarily aim to use social media to drive referrals to their own news websites. Others pursue an off-site strategy and primarily aim to reach younger and hard-to-reach-audiences directly on the social media platforms with native content. Some public service media have a very clear strategy and focus on either on-site or off-site, while others pursue a mix, sometimes pursuing on-site referrals via one platform but off-site reach via another. In addition, a subset of organisations also invests additional resources in using social media to interact more with their audience, arguing this is part of their public service role.

Despite these differences in strategic goals, we find that day-to-day tactics are surprisingly similar, as they are shaped by the incentives created by platform companies and by social media teams imitating what they see as best practices.

Beyond this, the public service media organisations we cover differ significantly in how much they have invested in social media teams. In line with what we have found elsewhere (Sehl et al 2016), those organisations who have the least autonomy from political actors invest the least in new digital efforts. In this way, as many of our interviewees stress, public service media’s social media strategies cannot be seen in a vacuum, but are part of wider efforts to adapt to an increasingly digital, mobile, and social media environment. They happen in the context of a range of external challenges such as discussions around the funding, role, or autonomy of public service media. These external challenges are in some cases as pressing as competition with private sector competitors or the rise of platform companies.

While changes in media consumption, as well as the media environment, are not something public service media can influence, they generally have greater control over the strategic and organisational choices they make about how to adapt to the media environment where social media and other platforms are increasingly important. In many cases, inherited structures and budgets still prioritise the traditional channels of TV and radio, which serve an older audience. It is clear from this report and our previous work that public service media who want to go beyond these legacy services and develop digital offerings to younger audiences, have to invest in these. As we show here, investments in bespoke approaches often deliver a return in terms of reach and engagement, but also leave public service media more reliant on the platforms they invest in, and more exposed to changes in their ranking algorithms and products. The strategic question for public service media is how they can seize the opportunities offered by digital media broadly and social media specifically without becoming unduly dependent on the platforms companies they increasingly rely on to reach their online audiences.

References

Arriaza Ibarra, K., Nowak, E., and Kuhn, R. 2015. ‘Introduction: The Relevance of Public Service Media in Europe’, in K. Ibarra Arriaza, E. Nowak, and R. Kuhn (eds), Public Service Media in Europe: A Comparative Approach. New York: Routledge, 1–8.

Benson, R., Powers, M., and Neff, T. 2017. ‘Public Media Autonomy and Accountability: Best and Worst Policy Practices in 12 Leading Democracies’. International Journal of Communication 11, 1–22.

Born, G. 2004. Uncertain Vision: Birt, Dyke and the Reinvention of the BBC. London: Secker & Warburg.

Brevini, B. 2013. Public Service Broadcasting Online: A Comparative European Policy Study of PSB 2.0. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Caplan, R. and boyd, d. 2018. ‘Isomorphism Through Algorithms: Institutional Dependencies in the Case of Facebook’. Big Data & Society January-June, 1-12. doi: 10.1177/2053951718757253.

Cherubini, F., and Nielsen, R. K. (2016). Editorial Analytics: How News Media are Developing and Using Audience Data and Metrics. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Cornia, A., Sehl, A., and Nielsen, R. K. 2016. Private Sector Media and Digital News. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Cornia, A., Sehl, A., and Nielsen, R. K. 2017. Developing Digital News in Private Sector Media. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Donders, K., and Moe, H. 2011. Exporting the Public Value Test: The Regulation of Public Broadcasters’ New Media Services Across Europe. Göteborg: Nordicom.

Humphreys, P. 2010. ‘EU State Aid Rules, Public Service Broadcasters’ Online Media Engagement and Public Value Tests: The German and UK Cases Compared’. Interactions: Studies in Communication and Culture 1(2), 171–84. doi: 10.1386/iscc.1.2.171_1.

Iosifidis, P. 2010. Reinventing Public Service Communication: European Broadcasters and Beyond. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kalogeropoulos, A., and Newman, N. 2017. ‘I Saw the News on Facebook’: Brand Attribution when Accessing News from Distributed Environments. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Loosen, W., and Schmidt, J. H. 2012. ‘(Re-)discovering the Audience: The Relationship Between Journalism and Audience in Networked Digital Media’. Information Communication & Society 15(6), 867–87. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.665467.

Newman, N., Richard, F., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D. A. L., and Nielsen, R. K. 2017. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Nicholls, T., Shabbir, N., and Nielsen, R. K. 2016. Digital-Born News Media in Europe. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Nicholls, T., Shabbir, N., and Nielsen, R. K. 2017. The Global Expansion of Digital-Born News Media. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Nielsen, R., and Ganter, S. A. 2017. ‘Dealing with Digital Intermediaries: A Case Study of the Relations Between Publishers and Platforms’. New Media & Society, Online first. doi: 10.1177/1461444817701318.

Sehl, A., Cornia, A., and Nielsen, R. K. 2016. Public Service News and Digital Media. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Sehl, A., Cornia, A., and Nielsen, R. K. 2017. Developing Digital News in Public Service Media. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Weberling, J. 2011. ‘Mapping Digital Media: Case Study: German Public Service Broadcasting and Online Activity’. Open Society Foundations, https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/uploads/b08d507c-446b-4073-b3d3-590663a5c241/mapping-digital-media-german-psb-online-activity-20111018.pdf.

List of Interviewees

Positions held at the time of the interviews

|

Finland (Yle) |

|

Timo Kämäräinen, executive online producer, news and current affairs, Yle Kristiina Tolvanen, online producer, news and current affairs, Yle |

|

France (France Télévisions and Radio France) |

|

Mohamed Belmaaza, senior product and editorial analyst of Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions |

|

Germany (ARD and ZDF) |

|

Christiane Krogmann, editor-in-chief of Tagesschau.de, ARD-aktuell, ARD Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau, ARD Sonja Schünemann, head of social media news, ZDF Elmar Theveßen, deputy editor-in-chief, ZDF |

|

Italy (Rai) |

|

Diego Antonelli, head of digital, news division, Rai Antonella Di Lazzaro, deputy director, digital division, Rai |

|

Poland (Polskie Radio) |

|

Piotr Chęciński, editor-in-chief of Polskieradio.pl, Polskie Radio |

|

United Kingdom (BBC) |

|

Fiona Campbell, controller mobile and online, BBC News Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC News James Montgomery, director digital development, BBC News |

1 Due to technical limitations, the usage data reported here is always for a global audience.

2 For discussions of the wider environment see also Arriaza Ibarra et al. 2015; Benson et al. 2017; Born 2004; Brevini 2013; Donders and Moe 2011; Humphreys 2010; Iosifidis 2010.

3 Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, interviewed by Alessio Cornia, 8 Dec. 2017.

4 Sonja Schünemann, head of social media news, ZDF, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 13 Dec. 2017.

5 http://www.ansa.it/english/news/2017/06/01/rai-dg-campo-dallorto-resignation-becomes-effective-3_4e4f56b3-0132-4401-87ae-857f10c743df.html.

6 James Montgomery, director digital development, BBC News, BBC, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 7 Dec. 2017.

7 Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC News, BBC, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 23 Nov. 2017.

8 Fiona Campbell, controller mobile and online, BBC News, BBC, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 7 Dec. 2017.

9 Elmar Theveßen, deputy editor-in-chief, ZDF, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 3 Jan. 2018.

10 Ibid.

11 Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau, ARD, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 13 Dec. 2017.

12 Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, interviewed by Alessio Cornia, 8 Dec. 2017.

13 Antonella Di Lazzaro, deputy director, digital division, Rai, interviewed by Alessio Cornia, 5 Dec. 2017.

14 Fiona Campbell, controller mobile and online, BBC News, BBC, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 7 Dec. 2017.

15 Christiane Krogmann, editor-in-chief of Tagesschau.de, ARD, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 11 Jan. 2018.

16 Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, interviewed by Alessio Cornia, 8 Dec. 2017.

17 Piotr Chęciński, editor-in-chief of Polskieradio.pl, Polskie Radio, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 3 Jan. 2018.

18 Elmar Theveßen, deputy editor-in-chief, ZDF, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 3 Jan. 2018.

19 Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC News, BBC, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 23 Nov. 2017.

20 Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau, ARD, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 13 Dec. 2017.

21 Sonja Schünemann, head of social media news, ZDF, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 13 Dec. 2017.

22 Ibid.

23 Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau, ARD, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 13 Dec. 2017.

24 Antonella Di Lazzaro, deputy director, digital division, Rai, interviewed by Alessio Cornia, 5 Dec. 2017.

25 Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau, ARD, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 13 Dec. 2017.

26 Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC News, BBC, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 23 Nov. 2017.

27 Mohamed Belmaaza, senior product and editorial analyst at Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, interviewed by Alessio Cornia,

6 and 14 Dec. 2017.

28 Sonja Schünemann, head of social media news, ZDF, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 13 Dec. 2017.

29 Ibid.

30 Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau, ARD, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 13 Dec. 2017.

31 Timo Kämäräinen, executive online producer, news and current affairs, Yle, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 2 Jan. 2018.

32 Sonja Schünemann, head of social media news, ZDF, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 13 Dec. 2017.

33 Christiane Krogmann, editor-in-chief of Tagesschau.de, ARD, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 11 Jan. 2018.

34 Piotr Chęciński, editor-in-chief of Polskieradio.pl, Polskie Radio, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 3 Jan. 2018.

35 Antonella Di Lazzaro, deputy director, digital division, Rai, interviewed by Alessio Cornia, 5 Dec. 2017.

36 Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC News, BBC, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 23 Nov. 2017.

37 Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, interviewed by Alessio Cornia, 8 Dec. 2017.

38 Timo Kämäräinen, executive online producer, news and current affairs, Yle, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 2 Jan. 2018.

39 Patrick Weinhold, team leader social media, ARD-aktuell/Tagesschau, ARD, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 13 Dec. 2017.

40 Mark Frankel, social media editor, BBC News, BBC, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 23 Nov. 2017.

41 Data from Parse.ly. Since 2012, Parse.ly has tracked referral traffic to major digital publishing sites. As of 2017, Parse.ly has over 2,500 sites in its network, which in aggregate see over 1 billion monthly unique desktop, mobile, and tablet devices.

42 James Montgomery, director digital development, BBC News, BBC, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 7 Dec. 2017.

43 Elmar Theveßen, deputy editor-in-chief, ZDF, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 3 Jan. 2018.

44 Timo Kämäräinen, executive online producer, news and current affairs, Yle, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 2 Jan. 2018.

45 Thibaud Vuitton, editor-in-chief of Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, interviewed by Alessio Cornia, 8 Dec. 2017.

46 Mohamed Belmaaza, senior product and editorial analyst at Franceinfo.fr, France Télévisions, interviewed by Alessio Cornia,

6 and 14 Dec. 2017.

47 Christiane Krogmann, editor-in-chief of Tagesschau.de, ARD, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 11 Jan. 2018.

48 James Montgomery, director digital development, BBC News, BBC, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 7 Dec. 2017.

49 Ibid.

50 Christiane Krogmann, editor-in-chief of Tagesschau.de, ARD, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 11 Jan. 2018.