| Statistics | |

| Population | 81m |

| Internet penetration | 89% |

Sascha Hölig and Uwe Hasebrink

Hans Bredow Institute for Media Research, Hamburg

The role of social media in promoting hate speech and so called ‘fake news’ has become a key issue ahead of federal elections, but most Germans continue to get their news from traditional media, with television still preferred.

Germany already has some of the toughest hate speech laws in the world but the government is looking to update these rules for the social media age. It is proposing a law to force social networks like Facebook to remove false or threatening postings promptly or face fines of up to €50m (US$54m). The issue has taken on more urgency because of concern by the country’s political establishment about the spread of racist content on social media, targeting more than 1 million migrants who have arrived in the last two years. It is feared that false information or powerful memes in social media could influence public opinion during the election campaign.

Facebook has responded by increasing the number of staff based in Germany and working with the nonprofit fact-checking organisation Correctiv to identify so-called ‘fake news’ and mark disputed content within news feeds.

At the same time a number of new brands have emerged with a focus on explanatory or constructive journalism. Perspective Daily is a web magazine that publishes just one story each day with a focus on possible solutions to a specific problem. Der Kontext focuses on a monthly in-depth web documentary explaining a complex issue.1 A new public service web TV service, Funk, has also been launched to reach the younger generation with a range of programming including news.

Despite these new developments, it is striking that only 60% of our respondents – all of whom use online for other purposes – choose to access news via websites, apps, or social media weekly. This is much lower than any other country in our survey, as is the use of social media for news (29%), which has decreased by 2 percentage points in the last year. This can be partly explained by the growth of messaging apps like WhatsApp, which is particularly popular in Germany. Even so there is a danger of over-estimating the role of social media and messaging in political decision-making. Only 7% of our German respondents say it is their main source of news; less than 2% ONLY use social media for news in a given week.

By contrast, Germans remain heavily attached to television news, especially the main public service evening news programmes, Tagesschau and Heute. While the weekly reach of television news remains relatively stable, newspaper readership has been falling steadily amongst all age groups.

Combined with the move to digital media, newspaper groups are increasingly struggling to fund large legacy newsrooms. The situation has been made worse by high usage of ad-blocking software (28%) online, especially with younger users. Several media companies are in legal disputes against providers of ad-blockers.

The appetite to pay for online news remains low in Germany (7%) but faced with declining revenue from print, publishers have been testing new approaches. Der Spiegel, one of the most popular brands online, launched a ‘read now, pay later’ model in June 2016. It hides some of its articles under a Spiegel Plus brand where readers are prompted to pay a small amount for the rest (€0.39 per article). Readers only pay when they reach a total of €5. Die Zeit has been offering free access to its premium articles (Z+) for email registration. Only later, once a certain number of items has been accessed, is a user asked to pay for a subscription.

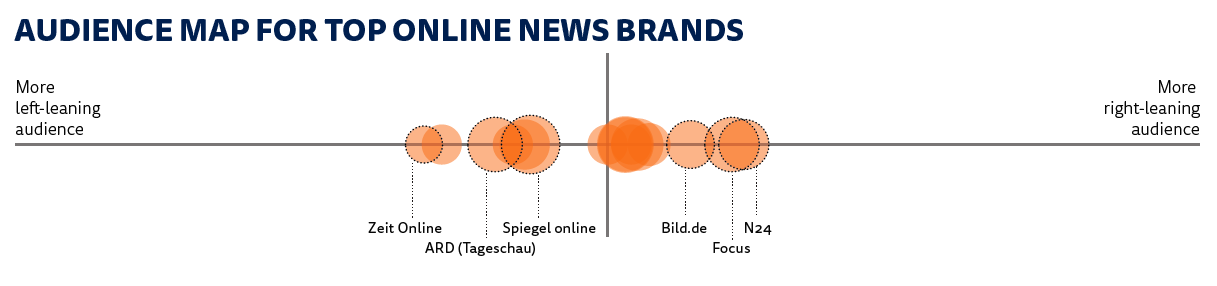

This year’s Digital News Report enables a deeper look at the way different brands are valued online. Tagesschau.de is considered best for accurate and reliable news and to understand complex matters. Spiegel online scores best for strong opinions and Bild.de performs best for amusing and entertaining content. Despite these differences, the most commonly used online media brands share a political view narrowly clustered around the political centre (see chart). There are no popular media brands espousing views at the political margins – in sharp contrast with highly polarised environments like the United States.

Changing Media

Television news maintains its substantial lead over online news, a much wider gap than in other countries. Print has also declined much further and faster than in other German-speaking countries such as Austria and Switzerland. The growth in social media has stopped.

Trust

About half of the Germans trust most news most of the time and it is widely felt to be free of political and commercial influence. Trust in the news is higher than in many countries but the media have increasingly come under criticism from the far right in particular for withholding news that might embarrass the corporatist consensus.