Executive Summary

Major outcomes continue to unfold nearly three years on from the global investigation known as the ‘Panama Papers’, first unveiled 3 Apr. 2016 in a wave of stories published simultaneously by news outlets in 76 countries. So far in 2019, Armenia has re-opened a corruption probe into a former top law enforcement official and Member of Parliament, US officials made the first arrest of an American implicated in the scandal, and a provincial minister was taken into custody by Pakistan’s National Accountability Bureau.

Collaborative global reporting projects like the Panama Papers raise anew the difficult question of how to measure and analyse the social impacts of journalism, and especially of investigative or ‘accountability’ reporting. Professional norms make journalists reluctant to weigh their work in terms of the results it produces, for fear of being seen as activists, but the question becomes more urgent as public affairs journalism increasingly relies on non-profit newsrooms supported by charitable giving or other subsidies. Meanwhile, global investigative projects are a new phenomenon and have rarely been studied in terms of impact.

This factsheet offers the first systematic overview of the impacts of Panama Papers reporting around the world. Based on results catalogued by reporters themselves, this preliminary analysis suggests how substantive policy impacts may be magnified for high-profile global investigations and points the way towards a more thorough cost-benefit analysis of such projects. We find that:

- The most reliable outcome of Panama Papers reporting around the world has been various forms of official deliberation and information-gathering, observed in 45 percent of countries tracked in this study.

- Nearly a fifth of countries tracked have seen at least one instance of concrete reform, such as a new law or policy designed to address problems exposed in the reporting. This is a higher rate than has been found in comparable analyses, due in part to the global scope of the Panama Papers and the nature of the institutions implicated.

- Various tax enforcement measures have been a regular outcome of the reporting, and numerous companies and individuals have been penalised or prosecuted as a result. Direct accountability for public officials remains rare, with officials losing office in fewer than 10 percent of countries tracked.

- Backlash against journalists was recorded almost as often as substantive reforms, though in different parts of the world: predictably, reporters have come under threat in countries that score low in press freedom.

The data assembled for this factsheet underscore how major investigative reports may continue to have significant impacts years after publication, and that substantive policy outcomes in particular require time to take shape. Our analysis reinforces recent research suggesting that accountability journalism may yield dramatic returns by the standards of social investment, as each dollar invested ‘can generate hundreds of dollars in benefits to society from changes in public policy’ (Hamilton 2016: 10).

Introduction

News is usually understood as a public good which yields broad social benefits beyond its commercial value. But journalism’s prosocial effects can be defined in different ways, none easy to measure: informing citizens, setting a common public agenda, holding power to account, and so on. Meanwhile, traditional newsroom ethics resist the idea that objective journalists should aim for or be evaluated by particular outcomes like changing policy, even among investigative reporters who expose public corruption and other social ills (Ettema and Glasser 1998).

Over the last decade, however, concern over the democratic consequences of the economic crisis in the news industry has sparked new interest in finding ways to measure the impacts of journalism – in particular of investigative reporting, which can require extraordinary newsroom investments but also have major effects. These efforts have yielded a spate of white papers proposing frameworks for evaluating impact, as well as new tools such as the Tow Center’s Newslynx and the Impact Monitor from the European Journalism Center.1 One major driver of this shift is newsrooms’ increasing reliance on the non-profit world (Konieczna 2018), where charitable foundations regularly evaluate the effectiveness of their grant-making (Keller and Abelson 2015). As an editor for the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) has explained,

In the nonprofit circles there does tend to be more open discussion around impact … For us, our funders, generally they’re philanthropists and foundations. They don’t have any potential financial gain from our stories but they still want to see value for the money they’re spending so we have to present that more and more in terms of impact (quoted in Konieczna and Powers 2017: 1553).

Investigative non-profits routinely monitor the real-world effects their stories produce, from media mentions to policy change. For instance, the ICIJ records outcomes of each investigation it conducts on an internal spreadsheet, and also publishes articles about major impacts on its website (Konieczna and Powers 2017). The Center for Investigative Reporting has an ‘Outcome Tracker’ built into its content management system where reporters note responses to their stories (Green-Barber 2014). ProPublica maintains an internal ‘Tracking Report’, updated daily, which records official reactions, ‘opportunities to influence change’ (hearings, commissions, etc.), and lasting impacts such as new regulations (Tofel 2013).

Despite growing attention to impact in some corners of the news industry, there has been little systematic research about the relative frequency of various kinds of outcomes, the factors that promote particular results, or how outcomes might vary in different political environments.2 This factsheet presents the first comprehensive overview of the impacts of a global reporting collaboration, the Panama Papers, which grew out of a trove of files from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca leaked to Süddeutsche Zeitung, and ultimately involved more than 500 reporters working in nearly 90 countries. Studying a project like the Panama Papers provides a unique opportunity to assess the impact of investigative journalism in a best-case scenario – the simultaneous global release produced front-page headlines around the world, and by the end of 2016 partners had published 4,700 stories. It also allows us to compare the kinds of results produced in different countries.

Approach

Data for this analysis come primarily from the ICIJ, the Washington-based non-profit news organisation which coordinated the Panama Papers investigation. The ICIJ maintains a public-facing blog reporting on impacts and other developments related to various collaborative reporting projects it has led, which includes 130 entries dealing with the Panama Papers posted between 3 Apr. 2016 and 3 Mar. 2019. These entries were reviewed in detail for references to outcomes of the investigation; additional references were culled from the Twitter feed of the ICIJ. Wherever possible, outcomes were confirmed and brought up to date with additional news searches.

This broadly replicates the method used by Hamilton (2016) in the most comprehensive analysis to date of the impacts of investigative journalism, based on identifying outcomes self-reported by journalists in prize entries submitted over 30 years to the IRE Awards, an annual competition by the US-based Investigative Reporters & Editors. That study applied a model originally developed by Protess et al. (1991: 240) to classify outcomes into three categories – deliberative, individualistic, and substantive – defined as follows:

Deliberative results occur when policy makers hold formal discussions of policy problems and their solutions, such as legislative hearings or executive commissions. Individualistic outcomes occur when policy makers apply sanctions against particular persons or entities, including prosecutions, firings, and demotions. Finally, substantive results include regulatory, legislative, and/or administrative changes.

References to outcomes from the ICIJ blog and supplemental sources were classified into those top-level categories applying a slightly modified version of the coding scheme used by Hamilton (2016: 93). (For instance, in this analysis ‘individualistic’ outcomes include tax enforcement measures which were a common result of the Panama Papers; ‘deliberative’ outcomes include instances of public protest as well as of cross-border data-swapping by regulators; and ‘substantive’ outcomes include rule changes by international bodies like the EU.) In addition, references to violence, threats, or restrictions directed against journalists were coded into a fourth top-level category, ‘backlash’.

It must be stressed that the events that follow a major story depend on a wide array of circumstances and can never be attributed definitively or exclusively to the reporting. Further, the self-reported data analysed here reflects journalists’ notions of what constitutes a relevant outcome. Finally, outcomes vary among Panama Papers countries in part because the substance of the story was different, and may have warranted different policy responses from place to place.

Results

Our content analysis of impact-related entries on the ICIJ blog yielded 147 distinct outcomes recorded for the Panama Papers investigation over 35 months. This tally includes aggregate results (eg multiple audits or fines) recorded as a single outcome; as noted, counting impacts is a subjective procedure and the value of the analysis lies in broad comparison across categories and countries. The most useful measure for such comparisons is outcome frequency, defined here as the percentage of jurisdictions covered in which at least one instance of a given impact was recorded.3

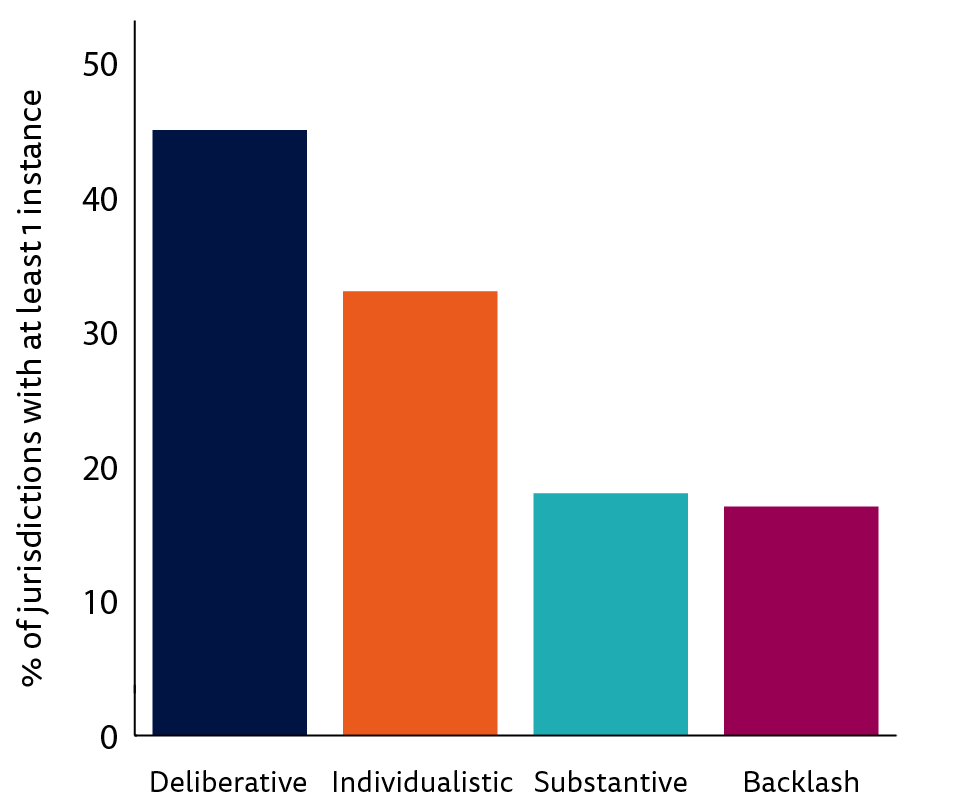

Findings for the three primary impact categories echo Hamilton’s (2016) analysis of IRE contest entries in the United States: deliberative results reflecting official discussion or investigation were most common, followed by individualistic outcomes that indicate accountability for specific actors. Least common were substantive impacts such as legal or regulatory reform. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Frequency of major impact types

At the same time, outcome frequency under all three of these categories was much higher than rates observed in the earlier study. As developed below, this likely reflects the scope and focus of the global investigation into offshore money flows, as well as differences in the underlying data set and the longer time period covered.

Substantive outcomes

In our data, 16 countries or international bodies achieved at least one substantive reform related to the Panama Papers by March 2019. This is equivalent to an impact frequency of 18 percent, using our baseline of 88 countries with ICIJ investigations – an impressive result.

Substantive outcomes included policy or regulatory shifts as well as new laws. In the US, for instance, the Obama Administration moved quickly to finalise banking rules cracking down on anonymous shell companies. (After delays, the regulations finally took force in 2018.) Across Europe, governments are in various stages of creating registries of companies’ true owners, in keeping with rules adopted by the European Parliament in April 2018.

Though concentrated in Europe and North America, substantial reforms have been visible in a range of countries. In October 2016, the Lebanese Parliament voted to lift bank secrecy protections, in order to avoid OECD blacklists being introduced the next year. Mongolia passed a law in April 2017 banning public officials and their family members from owning offshore companies. Panama adopted OECD reporting standards in 2018 and finally criminalised tax evasion in early 2019, after being repeatedly blacklisted.

Reforms often followed substantial deliberation and took time to develop. In Canada, for instance, coverage of the Panama Papers sharpened public criticism of a tax-amnesty program that waived interest and penalties for many wealthy taxpayers who voluntarily disclosed hidden assets. The controversy led to a parliamentary inquiry as well as an expert panel commissioned by the tax agency, which proposed tighter rules in April 2017 based on those recommendations; after public review and further tweaks, the reforms went into effect in March 2018.

The impressive results here also likely reflect the very high profile of the Panama Papers coverage, as well as the particular subject matter. The world of international banking and corporate taxation is an intensely rule-bound domain governed by fairly strong international regimes; a shift in policy at the level of the OECD or EU can effectively require reforms in dozens of countries. Further, the revelations drew sustained attention from prominent international campaigning organisations, such as Transparency International, which focus on the issues of corruption and money-laundering.

Individualistic outcomes

Consequences for people or companies implicated in the Panama Papers directly or indirectly, ranging from civil or criminal action to political outcomes, accounted for roughly 30 percent of results in our data and were visible all around the world. At least one such outcome was recorded for one-third of jurisdictions tracked.

Attention has been lavished on cases in which prominent political figures paid a price after being exposed in the Panama Papers. Most famously, Iceland’s prime minister stepped down under pressure just two days after the stories broke in 2016, revealing his family’s interest in an offshore firm that stood to gain from the bailout of failed Icelandic banks. In Pakistan, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was forced to resign, barred from holding high office, fined $10.6 million, and finally sentenced to imprisonment twice in 2018 on separate corruption charges stemming from the leaks.

However, such outcomes are fairly rare in our data. We find that just 8 percent of jurisdictions in our data set saw any public official resign or be removed from office in connection with the revelations. (This is slightly higher than in Hamilton’s IRE data, which found references to officials resigning in 6 percent of cases, for instance.) We identified six cases of current or former high officials facing some form of direct accountability, such as being prosecuted or forced from office.

More common among individualistic outcomes are various civil or criminal measures to penalise private actors exposed in the leaks or during the resulting audits and investigations. This includes several actions against major banks, such as European regulators shutting down Malta’s Pilatus Bank and a $180 million penalty against Taiwan’s Mega ICBC by New York’s bank authority, as well as penalties against Mossack Fonseca offices in multiple jurisdictions. Various forms of tax enforcement, such as fees, fines, and recouping back taxes, account for more than a third of individualistic outcomes.

Deliberative outcomes

Deliberative outcomes that indicate official steps to understand a problem or identify possible solutions were the most consistent result of the Panama Papers reporting, with an outcome frequency of 45 percent. This rate reflects only explicit references and likely understates the actual extent of such measures.

The prevalence of deliberative outcomes is not surprising, and echoes previous research into the impacts of accountability reporting (discussed below). The first and easiest recourse for officials confronted with headlines about some failure of governance is to launch an inquiry or appoint a commission. And as noted, substantive reforms often take years to emerge and typically follow one or more forms of public deliberation.

In our analysis, deliberative outcomes encompassed investigations by any public agency as well as parliamentary inquiries or hearings, dedicated commissions or taskforces, and intergovernmental or interagency meetings to swap data and coordinate investigations. They also included specific reforms proposed publicly either through legislation or by a government agency.

Investigations were by far the most common deliberative result, with at least one instance in 34 percent of jurisdictions tracked, again confirming earlier research. This reflects the breadth of the category, which also includes civil and criminal inquiries leading to individualistic outcomes. Commissions, taskforces, hearings, and similar forums were evident in just under 10 percent of jurisdictions, while public demonstrations took place in 3 percent.

Backlash

In addition to outcomes reflecting the potential social return of the Panama Papers investigation, we also coded for instances of backlash against journalists or media organisations referenced by the ICIJ blog. This analysis indicates that 17 percent of countries covered experienced at least one instance of backlash – just slightly under the rate of substantive outcomes.

However, this figure includes a wide range of anti-press measures or threats. The most severe are two instances of journalists who may have been murdered in connection to their reporting: in Malta, Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed by a car bomb in October 2017, and in Slovakia, Ján Kuciak and his fiancée were shot to death in February 2018. (Kuciak had worked on the Panama Papers and ‘Paradise Papers’ stories but in the months before his murder was investigating possible Mafia ties of the Slovak prime minister.)

In other cases, journalists lost their jobs in apparent connection with the Panama Papers. For instance, in April 2016, a top editor of Hong Kong daily Ming Pao was unexpectedly fired – supposedly to cut costs – on the same day the paper carried front-page reports on prominent political and business figures who appeared in the Panama Papers documents. In Venezuela, a reporter for regime-friendly outlet Últimas Noticias was fired for working with the ICIJ.

The backlash statistic also covers more than a dozen cases in which journalists or news organisations were threatened or restricted, sometimes preemptively. In China, for instance, censors reportedly instructed outlets to delete articles related to the Panama Papers, while in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the communications minister publicly warned journalists to be ‘very careful’ about naming names appearing in the data.

With few exceptions – for example, Finnish tax authorities threatened to raid reporters’ homes to seize documents – backlash has been concentrated in regions with poor records for press freedom. The 15 countries where instances of backlash were recorded have a median ranking of 92 in the World Press Freedom Index (equivalent to Ecuador’s position about halfway down the list).

Discussion

The results presented here offer compelling evidence of the powerful impact that high-profile investigative journalism can have in terms of drawing public attention to a problem, prompting authorities to hold people accountable, and in many cases helping to bring about long-term change. This analysis relies on self-reported data reflecting journalists’ judgement of outcomes that can be linked to their work. Nevertheless, it may understate the extent of the impact, as the ICIJ network may not have recorded every development stemming from the Panama Papers controversy in all of the countries covered.

The comparison with Hamilton’s (2016) analysis of impacts recorded in IRE prize entries is particularly instructive. Our data confirm the finding that deliberative outcomes (led by investigations, more than twice as common as any other result in both studies) are the most consistent impact of investigative journalism, followed by individualistic and then substantive outcomes. As Hamilton (2016: 94) notes,

Impacts vary in their costs. Talk may be cheap, compared to disciplining an individual bad actor. Changing the substance of policy or the operation of an institution may be the most costly outcome, since it can involve collective action to pressure for change, the operation of group decision-making processes, and ultimately shifts in resources.

At the same time, all three classes of impact occur with higher frequency in our data than in the earlier study. Hamilton observed especially low rates of substantive impact – for instance, references to new legislation in fewer than 2 percent of IRE prize entries. While the two data sets are not directly comparable, one reason for the difference is that our results reflect nearly three years of public responses to the Panama Papers.4 As noted above, substantive changes like legal or regulatory reform often follow extensive deliberation (reflected in their frequent co-occurrence in our data) and may take years to develop (see also Hird 2018).

The distribution of impacts around the world also offers food for thought. As shown in Figure 2, a cluster of relatively wealthy democracies in Europe and North America, led by the European Union itself, exhibited a distinct pattern: one or more substantive outcomes, almost always in combination with deliberative and individualistic results, and rarely with evidence of backlash against journalists. This underscores the role of strong deliberative and policymaking institutions in promoting substantive responses to public controversy. However, only two jurisdictions recorded more than one substantive reform, and it is important to note that our results don’t speak to whether changes were far-reaching or merely cosmetic.

A much wider range of countries, covering nearly every region, saw either a combination of deliberative and individualistic impacts, or only some form of deliberation. (In many cases the deliberative outcome was an investigation which could lead to an individualistic result like levying fines, recouping taxes, or criminal prosecution.) And finally, a cluster of countries including several notably authoritarian regimes – eg, China, Russia, and Turkey – saw only instances of backlash.

Figure 2. Impacts recorded by country and category

Some 34 jurisdictions in our data set, just under 40 percent, either saw no impact or only backlash (using baseline of 88 countries covered).

References

Ettema, J. S., and Glasser, T. L. 1998. Custodians of Conscience: Investigative Journalism and Public Virtue. New York: Columbia University Press.

Green-Barber, L. 2014. Waves of Change: The Case of Rape in the Fields. Berkeley, CA: Center for Investigative Reporting.

Hamilton, J. 2016. Democracy’s Detectives: The Economics of Investigative Journalism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Hird, C. 2018. Investigative Journalism Works: The Mechanism of Impact. January. London: The Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

Investigative Impact: A Report on Best Practices in Measuring the Impact of Investigative Reporting 2017, November. Silver Spring, MD: Global Investigative Journalism Network.

Keller, M., and Abelson, B. 2015. Newslynx: A Tool for Newsroom Impact Measurement. June. New York: Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

Konieczna, M. 2018. Journalism Without Profit: Making News When the Market Fails. New York: Oxford University Press

Konieczna, M. and Powers, E. 2017. ‘What Can Nonprofit Journalists Actually do for Democracy?’ Journalism Studies 18(12): 1542–1558. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2015.1134273.

Obermayer, B. and Obermaier, F. 2017. The Panama Papers: Breaking the Story of How the Rich and Powerful Hide their Money. London: Oneworld Publications.

Protess, D. L., Cook, F. L., Doppelt, J. C., et al. 1991. The Journalism of Outrage: Investigative Reporting and Agenda Building in America. New York: Guilford Press.

Tofel, R. J. 2013. Non-Profit Journalism: Issues around Impact. New York: ProPublica.

1 A useful recent overview of these initiatives is Investigative Impact: A Report on Best Practices in Measuring the Impact of Investigative Journalism, a 2017 report from the Global Investigative Journalism Network.

2 A notable exception is James Hamilton’s recent work on the economics of investigative journalism, discussed below, which uses a large-scale analysis of impacts reported by journalists to show, for instance, how effects of a story depend on the medium, size of the outlet, and the focus of the investigation.

3 We use a baseline of 88 jurisdictions where significant Panama Papers reporting took place to calculate frequency, based on the ICIJ’s published list of reporting partners. It is important to note that our impact data includes responses by countries not on the list as well as international bodies such as the EU and OECD (see Figure 2).

4 As Hamilton (2016: 92) notes, IRE prize entries cover reporting during the previous 12 months and will not capture impacts that take longer to emerge, meaning that substantive outcomes in particular may be underreported.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Reuters Institute’s research team for helpful comments on the data and analysis presented here. Thanks also to Magda Konieczna for ongoing discussions about these themes; this factsheet grows out of a larger research project by Graves and Konieczna studying impacts of the Panama Papers in different parts of the world.

About the authors

Lucas Graves is acting Director of Research and Senior Research Fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism

Nabeelah Shabbir is a freelance journalist, formerly of the Guardian

Published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism with the support of the Google News Initiative