This year’s report comes against the backdrop of rising populism, political and economic instability, along with intensifying concerns about giant tech companies and their impact on society. News organisations have taken the lead in reporting these trends, but also find themselves challenged by them – further depressing an industry reeling from more than a decade of digital disruption. Platform power – and the ruthless efficiency of their advertising operations – has undermined news business models contributing to a series of high-profile layoffs in traditional (Gannett) and digital media (Mic, BuzzFeed) in the early part of 2019. Political polarisation has encouraged the growth of partisan agendas online, which together with clickbait and various forms of misinformation is helping to further undermine trust in media – raising new questions about how to deliver balanced and fair reporting in the digital age.

Against this background we are seeing some real shifts of focus. News organisations are increasingly looking to subscription and membership or other forms of reader contribution to pay the bills in a so-called ‘pivot to paid’. Platforms are rethinking their responsibilities in the face of events (Christchurch attacks, Molly Russell suicide) and regulatory threats, with Facebook rebalancing its business towards messaging apps and groups – the so-called ‘pivot to private’. Meanwhile audiences continue to embrace on-demand formats with new excitement around podcasts (New York Times, Guardian) and voice technologies – the so-called ‘pivot to audio’.

And amid all this frenetic change, some are beginning to question whether the news media are still fulfilling their basic mission of holding powerful people to account and helping audiences understand the world around them. The questioning comes in the form of government inquiries in some countries into the future sustainability of quality journalism (with recommendations as to what can be done to support it). But it also comes from parts of the public who feel that the news media often fall short of what people expect from them.

Our report this year, based on data from almost 40 countries and six continents, aims to cast light on these key issues, principally through our survey data but supplemented with in-depth qualitative research on the news habits of young people in the UK and US. The overall story is captured in this Executive Summary, followed by Section 1 with chapters containing additional analysis on key themes and then individual country pages in Section 2 carrying additional context provided by local experts in each market.

Here is a summary of some of the most important findings from our 2019 research.

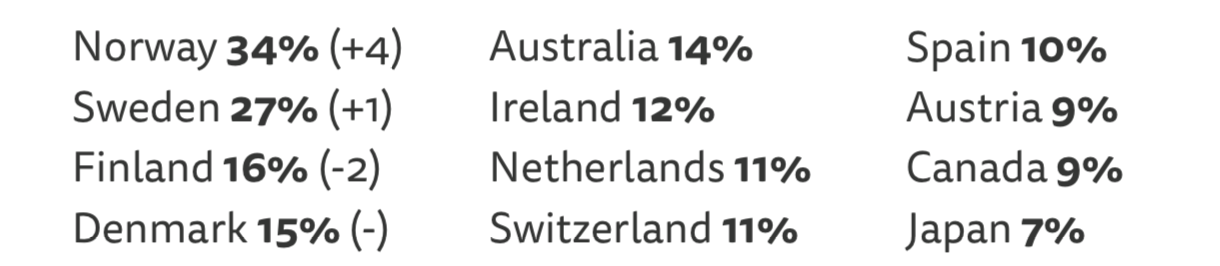

- Despite the efforts of the news industry, we find only a small increase in the numbers paying for any online news – whether by subscription, membership, or donation. Growth is limited to a handful of countries mainly in the Nordic region (Norway 34%, Sweden 27%) while the number paying in the US (16%) remains stable after a big jump in 2017.

- Even in countries with higher levels of payment, the vast majority only have ONE online subscription – suggesting that ‘winner takes all dynamics’ are likely to be important. One encouraging development though is that most payments are now ‘ongoing’, rather than one-offs.

- In some countries, subscription fatigue may also be setting in, with the majority preferring to spend their limited budget on entertainment (Netflix/Spotify) rather than news. With many seeing news as a ‘chore’, publishers may struggle to substantially increase the market for high-priced ‘single title’ subscriptions. As more publishers launch pay models, over two-thirds (70%) of our sample in Norway and half (50%) in the United States now come across one or more barriers each week when trying to read online news.

- In many countries, people are spending less time with Facebook and more time with WhatsApp and Instagram than this time last year. Few users are abandoning Facebook entirely, though, and it remains by far the most important social network for news.

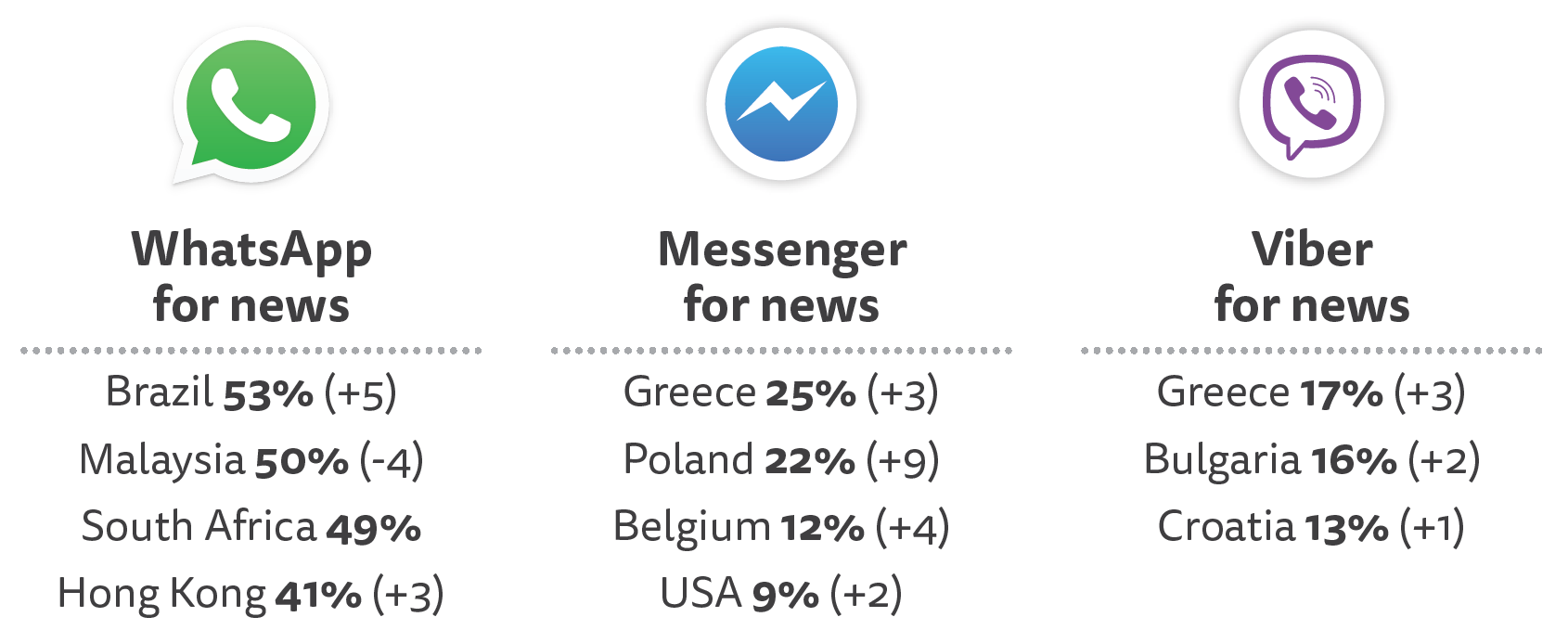

- Social communication around news is becoming more private as messaging apps continue to grow everywhere. WhatsApp has become a primary network for discussing and sharing news in non-Western countries like Brazil (53%) Malaysia (50%), and South Africa (49%).

- People in these countries are also far more likely than in the West to be part of large WhatsApp groups with people they don’t know – a trend that reflects how messaging applications can be used to easily share information at scale, potentially encouraging the spread of misinformation. Public and private Facebook Groups discussing news and politics have become popular in Turkey (29%) and Brazil (22%) but are much less used in Western countries such as Canada (7%) or Australia (7%).

- Concern about misinformation and disinformation remains high despite efforts by platforms and publishers to build public confidence. In Brazil 85% agree with a statement that they are worried about what is real and fake on the internet. Concern is also high in the UK (70%) and US (67%), but much lower in Germany (38%) and the Netherlands (31%).

- Across all countries, the average level of trust in the news in general is down 2 percentage points to 42% and less than half (49%) agree that they trust the news media they themselves use. Trust levels in France have fallen to just 24% (-11) in the last year as the media have come under attack over their coverage of the Yellow Vests movement. Trust in the news found via search (33%) and social media remains stable but extremely low (23%).

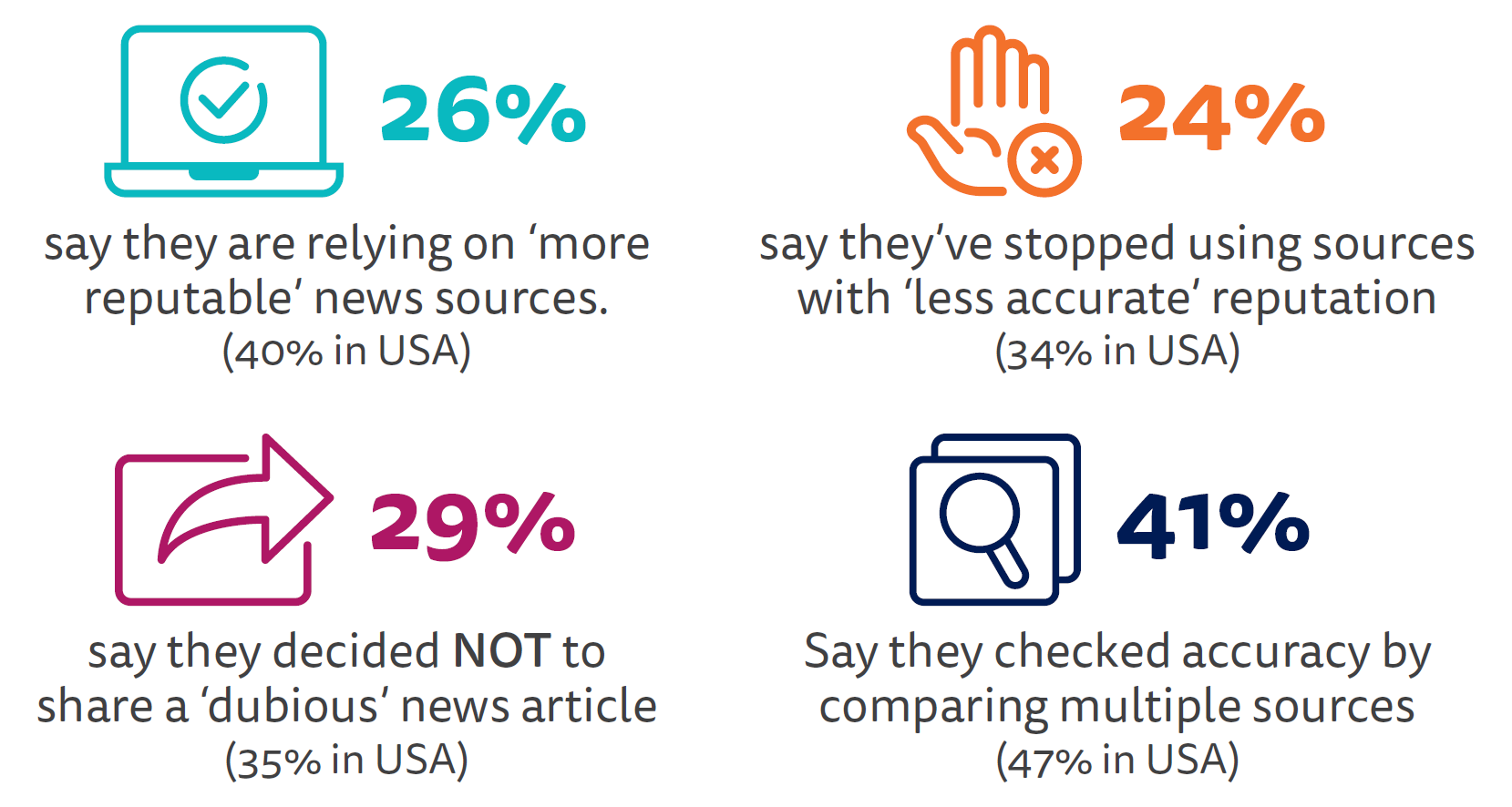

- Worries about the quality of information may be good for trusted news brands. Across countries over a quarter (26%) say they have started relying on more ‘reputable’ sources of news – rising to 40% in the US. A further quarter (24%) said they had stopped using sources that had a dubious reputation in the last year. But the often low trust in news overall, and in many individual brands, underlines this is not a development that will help all in the industry.

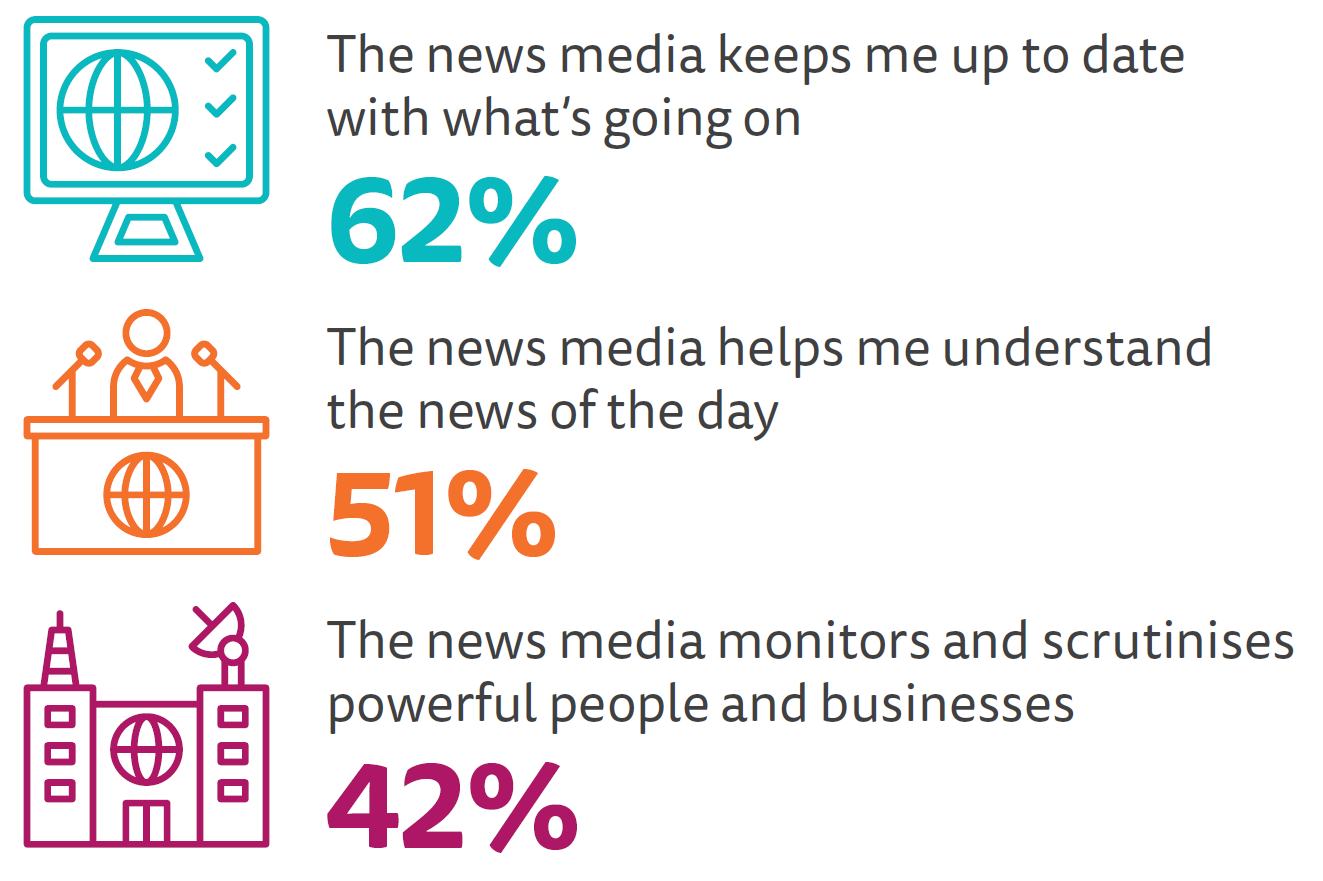

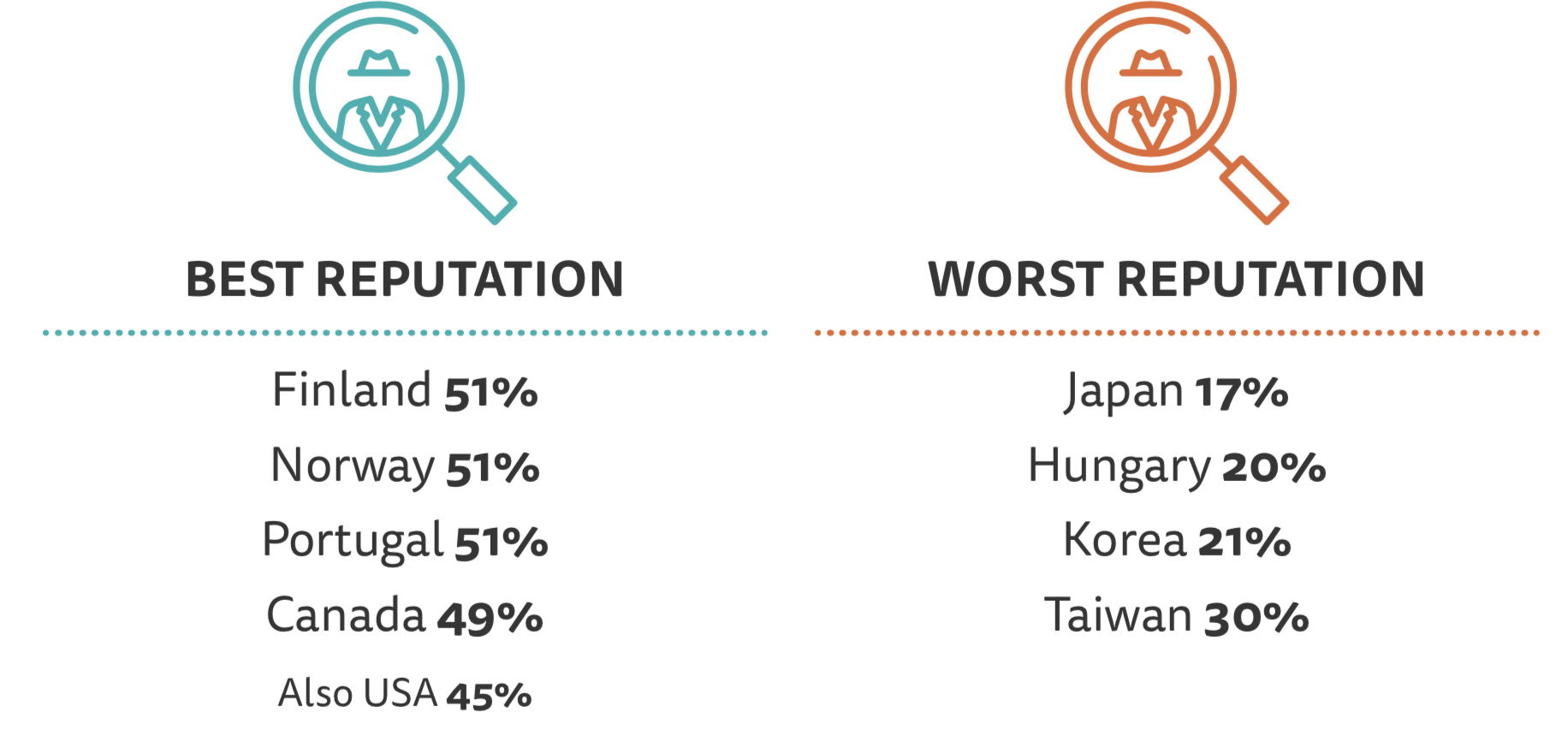

- The news media are seen as doing a better job at breaking news than explaining it. Across countries, almost two-thirds feel the media are good at keeping people up to date (62%), but are less good at helping them understand the news (51%). Less than half (42%) think the media do a good job in holding rich and powerful people to account – and this figure is much lower in South Korea (21%), Hungary (20%), and Japan (17%).

- There are also significant differences within countries, as people with higher levels of formal education are more likely to evaluate the news media positively along every dimension than the rest of the population, suggesting that the news agenda is more geared towards the interests and needs of the more educated.

- To understand the rise of populism and its consequences for news and media use, we have used two questions to identify people with populist attitudes, and compared their news and media use with those of non-populists. People with populist attitudes are more likely to identify television as their main source of news, more likely to rely on Facebook for online news, and less likely to trust the news media overall.

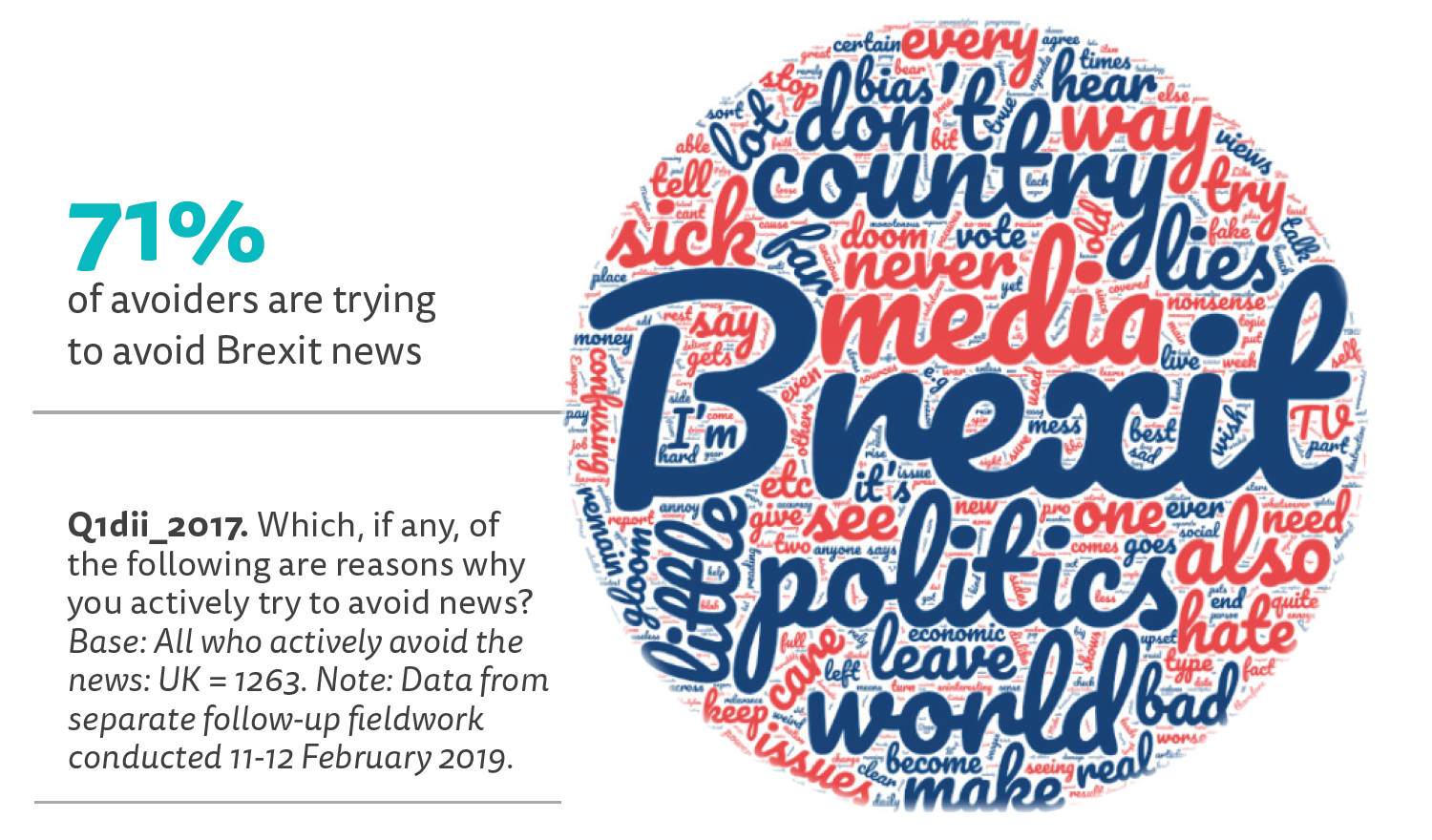

- More people say they actively avoid the news (32%) than when we last asked this question two years ago. Avoidance is up 3 percentage points overall and 11 points in the UK, driven by boredom, anger, or sadness over Brexit. People say they avoid the news because it has a negative effect on their mood (58%) or because they feel powerless to change events.

- The smartphone continues to grow in importance for news, with two-thirds (66%) now using the device to access news weekly (+4pp). Mobile news aggregators like Apple News and Upday are becoming a more significant force. Apple News in the United States now reaches more iPhone users (27%) than the Washington Post (23%).

- The growth of the smartphone has also been driving the popularity of podcasts, especially with the young. More than a third of our combined sample (36%) say they have consumed at least one podcast over the last month but this rises to half (50%) for those under 35. The mobile phone is the most used device (55%) for podcast listening.

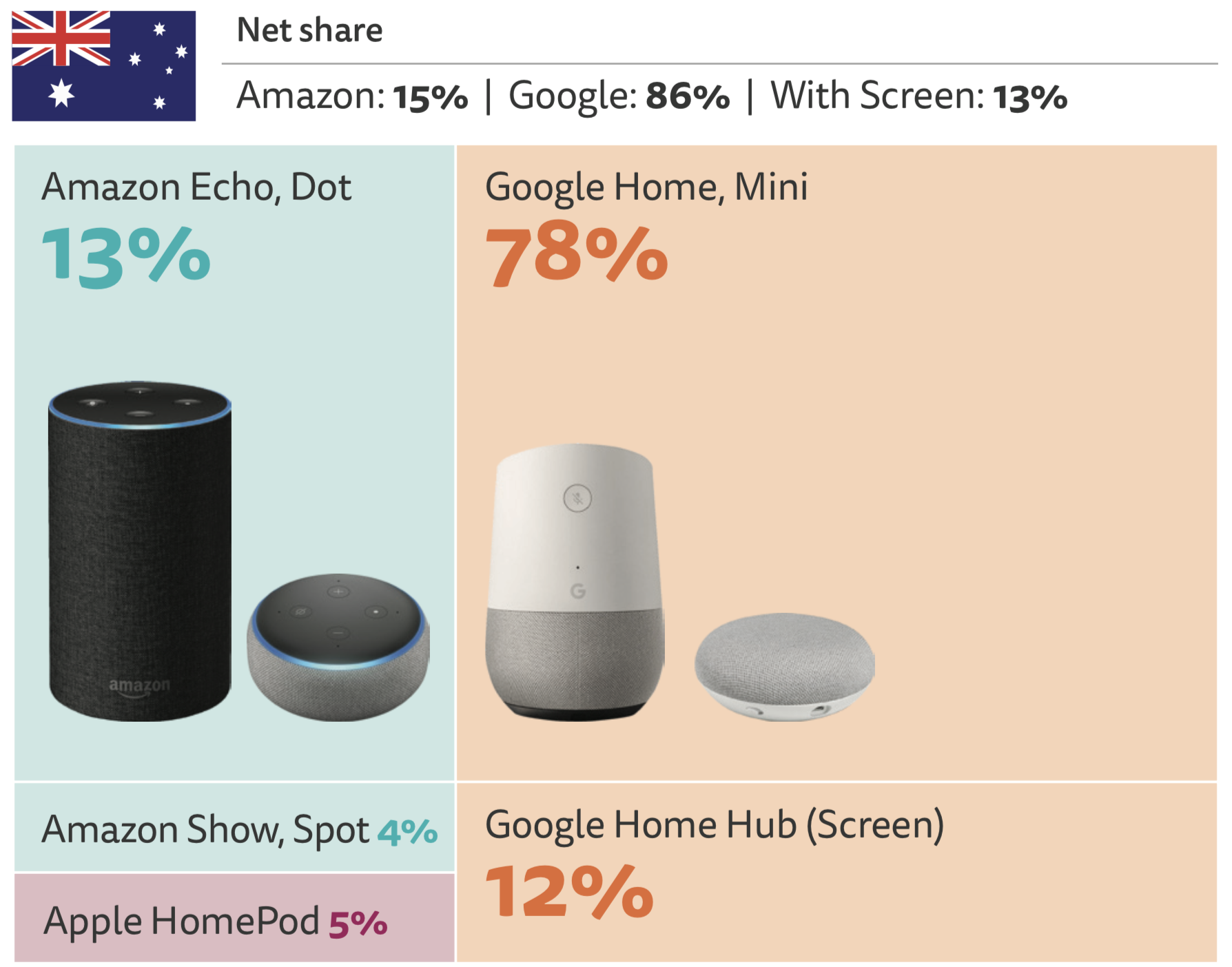

- Voice-activated smart speakers like the Amazon Echo and Google Home continue to grow rapidly. Usage for any purpose has risen from 9% to 12% in the United States, from 7% to 14% in the UK, from 5% to 11% in Canada, and from 4% to 8% in Australia. Despite this, we find that usage for news remains low in all markets.

Some Growth Left But the Limits around ‘Single Publication’ News Subscription Become Clear

In the last year a number of publishers have added paywalls and membership schemes while others have reported significant increases in digital subscription, but our data suggest this has not yet had a substantial impact. We see a slight increase in online payment in some countries and a stable picture in the US (after a big jump in 2017) but in general we have seen little change in the last six years. The proportion paying for news (subscriptions, memberships, donations, and other one-off payments) has remained stable at 11% in nine countries (averaged) that we have been following since 2013. Most people are not prepared to pay for online news today and on current trends look unlikely to pay in the future, at least for the kind of news they currently access for free.

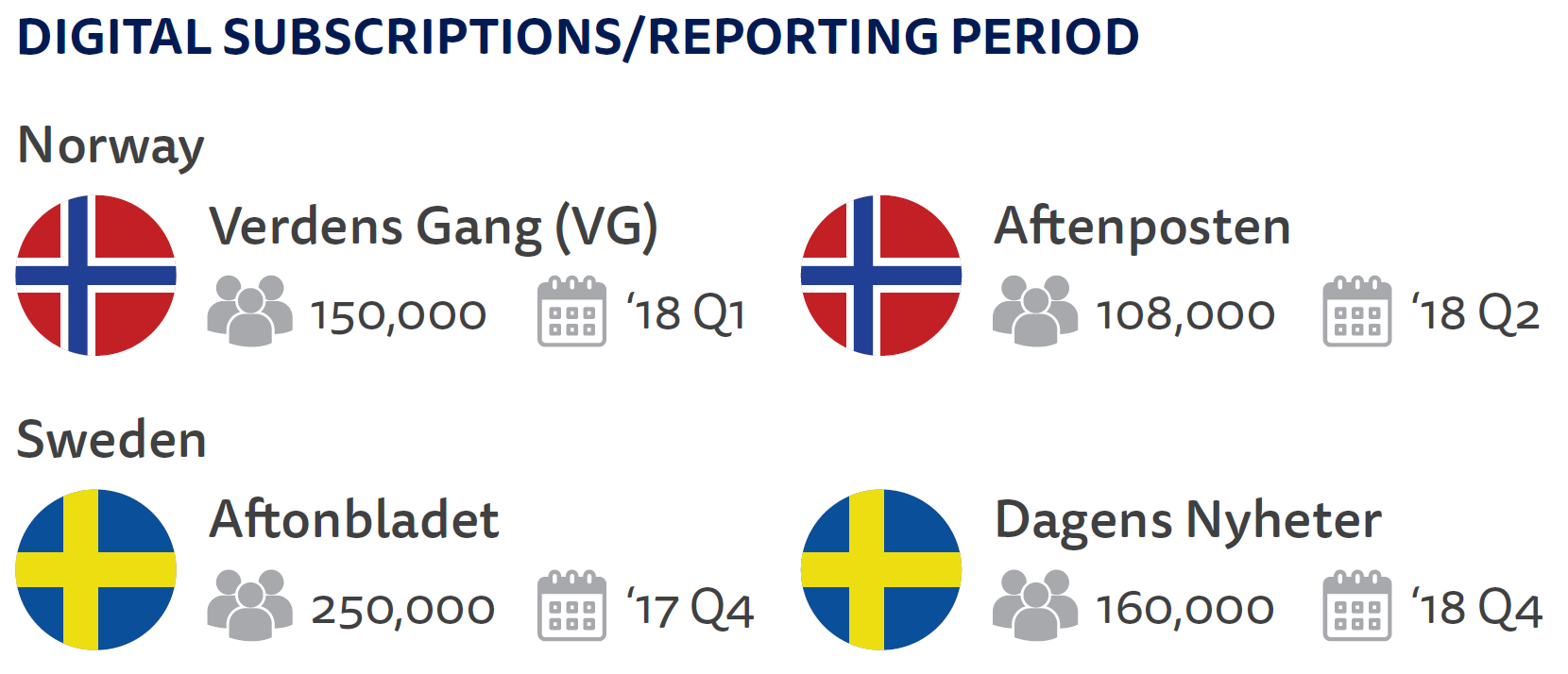

With the exception of the United States, the biggest growth has taken place in two markets, Norway and Sweden, where a small number of media houses have a strong position. Schibsted, as one example, reaches around 80% of consumers in both countries1 and, since 2016, has focused many of its quality and tabloid brands on premium, metered, and hybrid subscription models.

This Nordic success story becomes even clearer when we look at digital-only subscribers, removing those who get digital access with a print subscription or those who have a subscription that is paid by someone else. Here we find 15% in Norway and 14% in Sweden, 6% in Finland and Denmark, but just 4% in the UK and 3% in Spain and Italy. The equivalent figure in the United States is 8%. This is a purer measure of those who are prepared to use their own money to pay for a single title online news subscription. On top of the raw numbers, industry data reveal that Norwegians and Swedes are prepared to pay online for tabloid titles VG and Aftenbladet (freemium models) as well as more upmarket titles such as AftenPosten and Dagens Nyheter.

Source:Digital Subscriptions data via FIPP 2019 Global Subscription Report . Dagens Nyheter via direct communication.

By contrast, in the United States, the main subscription focus has been at the quality end of the market. The New York Times now has over 3m digital subscribers (out of a total of 4 million) and the Washington Post around 1m. Overall almost one in ten (8%) of our US sample are digital-only subscribers (up from 3% in 2016). Global brands like the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times have also clocked impressive numbers. The FT recently passed 1m total subscribers – around 740,000 of whom are digital-only.

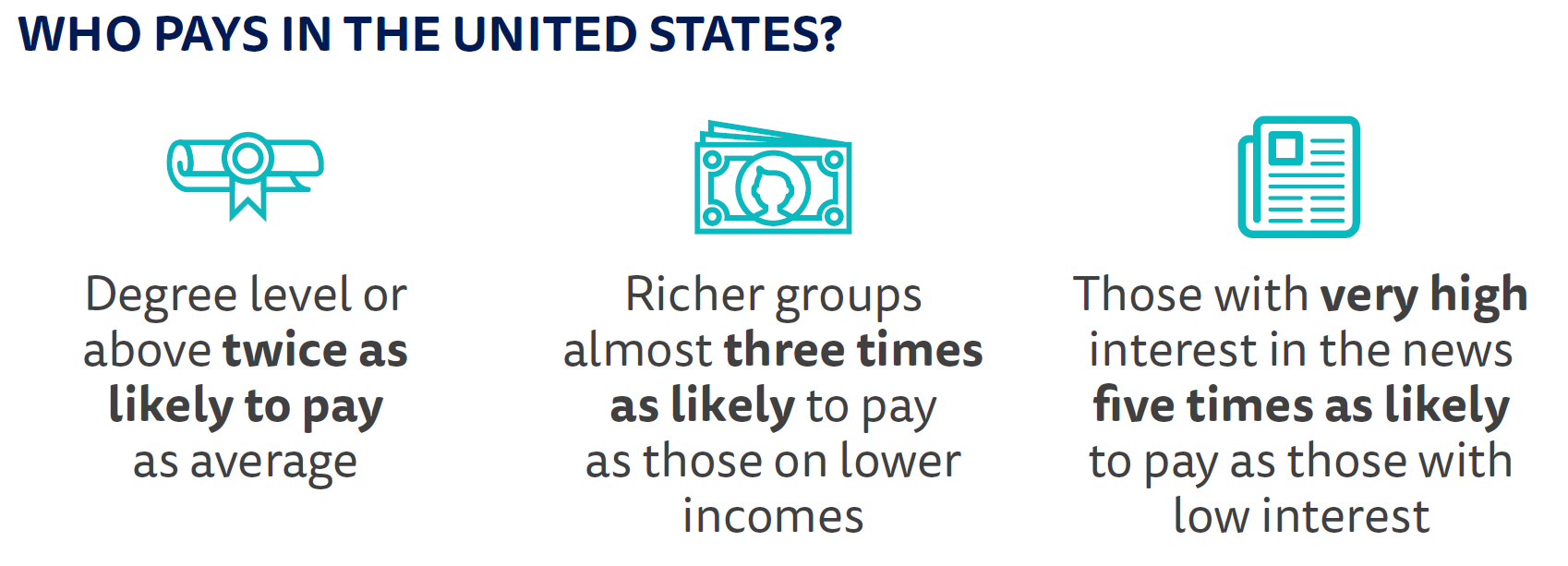

USA: 2012, Degree or above; 648, Extremely interested 694, Somewhat or less 632, Highest incomes; 445, Lowest incomes 462

Digital Subscriptions via FIPP 2019 Global Subscription report.

* Washington Post approx. figures

But these big brand successes are not replicated across the US market. A recent Business Insider survey showed the New York Times and Washington Post together attracting more than half of all of US news subscribers,2 while our data show few people are currently prepared to pay for more than one online news subscription. In Germany, for example, 70% of those that pay have just one subscription. Only 10% are prepared to pay for three or more (see next chart). This means that though big national brands like Bild (423,000 digital subscribers) and Zeit (105,000) are having some success in charging for online news it may be hard to persuade people to pay for another national or local paper. This may help explain why very few local or regional publishers report success with digital subscription models. – outside of the Nordic countries, France (Ouest-France and Nice-Matin), and some major cities in the US.

The US and Nordic countries have shown the potential for considerable growth in paid content, but these are rich countries where news has historically had a high reputation and value – something that may not be replicable elsewhere. The dominance of a few big national and global brands suggests that others may need to look at alternative models or at least ones where subscription is just part of a more diversified revenue strategy.

News Now Competes with Other ‘More Attractive’ Media Bundles

At the same time as news publishers are asking for online payments and memberships, entertainment providers such as Netflix, Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Prime are generating billions of dollars via premium services. Netflix alone has around 150m subscribers including 60m in the United States. But might the growth of these services – along with sport, online gaming, dating, and media storage – mean that there will be less appetite to pay for news? While the ‘culture of free’ that many associate with the internet is clearly evolving, some worry about the impact of so-called subscription fatigue – the notion that people are becoming frustrated with being asked to pay separately for many different services online. In the light of these concerns, we asked people what online media subscription they would pick if they could only have one for the next 12 months. Not surprisingly, news comes low down the list when compared with other services such as Netflix and Spotify – especially for the younger half of the population.

PROPORTION OF UNDER 45S THAT WOULD PICK EACH IF THEY COULD ONLY HAVE ONE ONLINE MEDIA SUBSCRIPTION FOR THE NEXT YEAR

Selected countries

Base: Under 45s: selected countries = 13,427.

Note. This question was asked in 14 countries: US, UK, France, Italy, Spain, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Belgium, Netherlands, Switzerland, Austria, Japan, Australia, and Canada.

Encouragingly, news fared considerably better with older groups (15%), but still lagged behind online entertainment services (30%). In previous years we have shown that young people are comfortable paying for online services, but news is not valued as much and is often seen as difficult or even a chore by comparison.

It’s probably awful but it’s an entertainment aspect. [People] are paying for a service that is giving them entertainment.

Amy UK, in-depth interview 2019

Growing Friction around News Consumption

Meanwhile we find evidence that the significant expansion of paywalls may be affecting user experience: 70% in Norway and around half in the USA, Denmark, Australia, and the Netherlands say they see payment barriers at least weekly. Heavy news users, digital subscribers, and younger users are even more likely to see these barriers.

PROPORTION THAT SEE A NEWS PAYWALL EACH WEEK

Norway and USA

Base: Total sample: Norway = 2013, USA = 2012.

The fear is that increased friction could put people off news entirely, especially those who are already under-engaged. On the other hand, it is possible that this is part of a transition in which more people accept that quality news provision needs to be paid for. In open-ended comments, we find some people accepting, some irritated, with others worried about the implications for democracy.

[Paywalls are] an understandable way to raise revenue in the face of decreasing ad revenue but I prefer the Guardian model, which doesn’t limit access to just those who can afford it.

Female, 43, UK

The majority of the population probably cannot and will not be able to afford to pay for good reporting services. This is a major issue for democracy worldwide.

Male, 34, UK

Further Bundling Ahead?

Our research suggests there may be a disconnect between current publisher strategies of selling individual titles (for a relatively high price) – and consumer desire for frictionless access to multiple brands. Almost half of those who are interested in news (49%) consume more than four different online sources each week – a number that rises significantly for under 35s.

Donation models, such as the one operated by the Guardian newspaper – and some local news organisations in the United States – have been suggested as an alternative to paywalls, but these still make up a small percentage of the market. In the last year just 3% gave money in the United States to a news organisation, 2% in Spain, and 1% in the UK.

Another alternative could be bundling and aggregation. The Times of London offers free access to the Wall Street Journal while the Washington Post bundles cheaper access via Amazon Prime. The New York Times is offering a joint subscription with Scribd while Dagens Nyheter in Sweden is partnering with Bookbeat around audio and ebooks.3 These added-value bundles may become more important as markets get saturated and customer retention becomes a burning issue. Growth is harder to come by in the United States, with 40% of new subscribers at the New York Times now joining up for cooking and crosswords – a different kind of bundling.4

Waiting in the wings come platform aggregators such as Apple News+, offering a single priced subscription for multiple premium titles for $9.99. Most premium news publishers have stayed out for now for risk of cannibalising their markets, but the industry will need to address consumer concerns about accessing multiple brands at a reasonable price sooner rather than later.

FRUSTRATION OVER PAYWALLS COULD PUSH CONSUMERS INTO THE ARMS OF AGGREGATORS

Gateways to News and the Rise of Aggregation

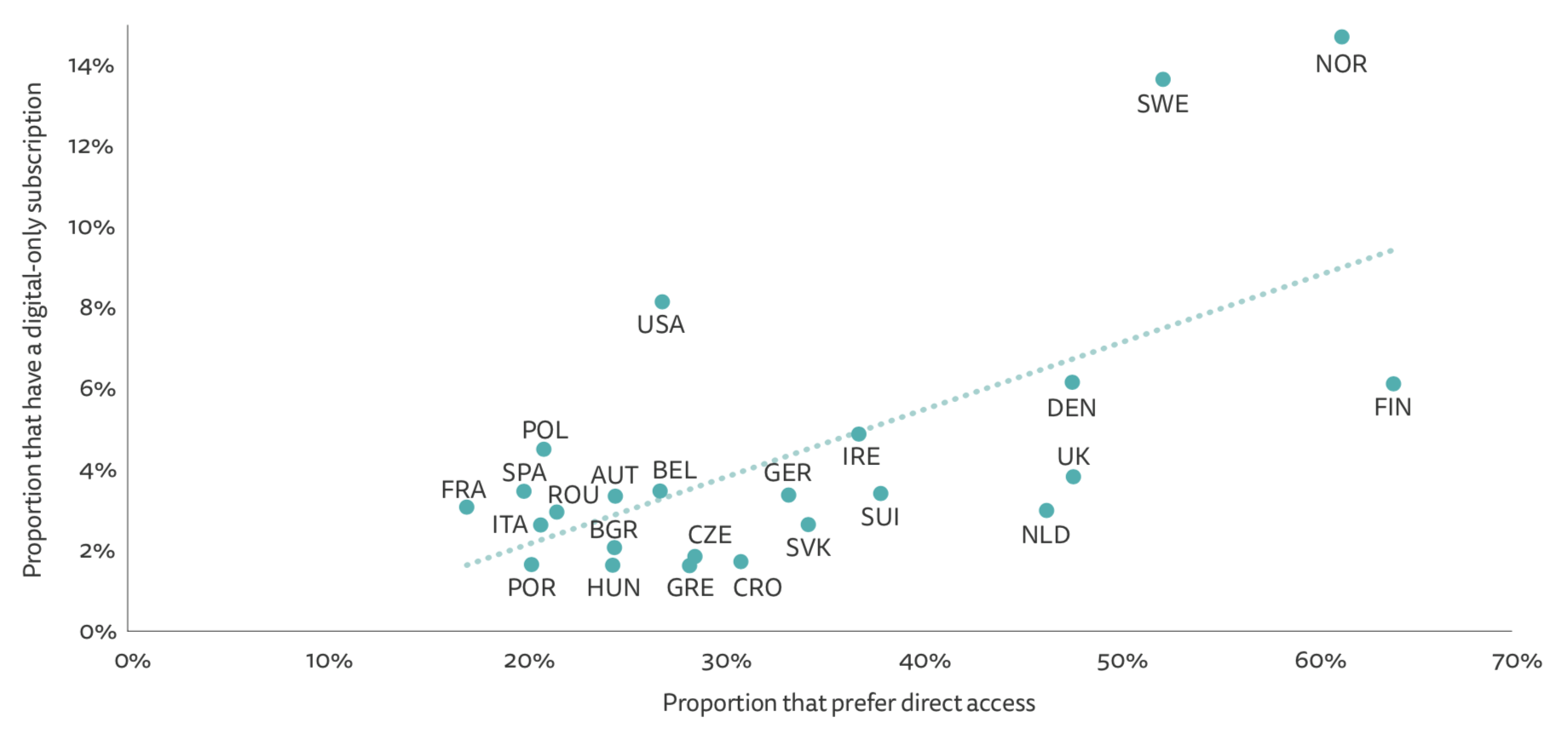

One of the biggest implications of the shift to online news has been the weakening of the direct relationship between readers and publishers. Across all our countries, just 29% now say they prefer to access a website or app directly – down 3 percentage points on a year ago. Over half of our combined sample (55%) prefer to access news through search engines, social media, or news aggregators, interfaces where large tech companies typically deploy algorithms rather than editors to select and rank stories.

Behind the averages, however, we find very significant country differences and can identify four types of access model. The first can be characterised as mainly direct, typified by Finland where almost two-thirds of respondents (64%) prefer to go first to a website or app. Elsewhere, preferred access is often social first, with over four in ten (42%) preferring this route in Chile and many other Latin American markets. In parts of Asia, publishers are deeply aggregated. In South Korea half (48%) say they prefer news via a search portal like Naver or Daum and 27% via a news aggregator. Just 4% prefer to go directly to a news website or app, by far the lowest in our survey. Finally, we see examples like the United States where many different routes to content are important – a pick and mix model. In all cases, younger groups are more likely to use social media and aggregators, with older groups more likely to access directly – so these models only go some way to explaining the complexity of access and distribution. When we look beyond main access routes most consumers, of course, are using a combination of these methods on a regular basis.

There are many reasons for these differences, which may relate to market size, competition, culture, and regulation, but either way it will clearly be harder for publishers who do not own the primary relationship with consumers to extract as much value from their content as those that do.

To test this hypothesis we have plotted digital-only subscription rates across countries with the proportion that access news sites and apps directly in the next chart.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PREFERENCE FOR DIRECT NEWS ACCESS AND DIGITAL NEWS SUBSCRIPTIONS

In the chart we see a clear link between direct preferences and online news payment. There are a few exceptions though. Finland, the UK, and Denmark have high direct traffic partly due to popular public broadcasters that do not charge for news (though this is also the case in Norway and Sweden). By contrast, the US has managed to drive higher online subscriptions despite lower direct traffic, partly because the election of Donald Trump sparked a wave of subscriptions and donations to liberal publications such as the New York Times.5 Overall, however, the biggest drivers of direct traffic (and subscription) are interest in news, and education, though age is also a factor.

The Role of Email and Mobile Notifications in Driving Loyalty

Generating more direct traffic to websites and apps is an important priority for publishers, with email newsletters a particularly favoured tactic for retaining subscribers but also for attracting new users. The Washington Post operates around 70 different newsletters and has found that recipients consume around three times as much content as those who don’t use email news. Our own data this year show that 42% of US digital subscribers have used one or more email newsletters in the last week – compared with 35% in the UK but just 17% in Norway and 19% in Sweden. It is clear this is one area where Nordic publishers could learn a few tricks from the United States.

Email remains extremely effective with older, highly engaged news users, even if overall usage has not grown over the last five years. By contrast, mobile notifications tend to be used by younger groups and have shown considerable growth in weekly use – up from 3% to 20% in the UK and 6% to 19% in the United States since 2014.

Heavy news users are 2.5 times more likely to use mobile alerts than casual news users. Publishers are learning how to use alerts more strategically6 – and not just for breaking news. Different content is now selected for different day-parts and also at weekends, while readers are being targeted individually with relevant content driven by artificial intelligence algorithms.

First Contact with the News; Shifting Preferences Over Time

This year we’ve taken a fresh look at the importance of gateways by bringing back a question about ‘first news use’ from 2016. In both the US and the UK we see fewer people starting each day with radio, TV, or print, with more people using the internet – mainly via smartphones. In the UK, the smartphone is now the main first gateway to news (28%) overtaking TV (27%).

Where do People Pick up First News on a Smartphone?

Around four in ten (43%) in the UK say they go to a news website or app first when using a smartphone, a relatively high figure almost certainly driven by the popularity of the BBC News app. The situation is reversed for under 35s with almost half starting their journey with social media (44%) and just a third going direct (34%). Overall, the proportion going direct is down 5 points from 48% in 2016 due to more going via homescreen links (11%) and aggregators.

In the United States, only one in five (20%) goes straight to a news app, down from 23% in 2016. Amongst under-35s only 13% go direct, with over half (54%) preferring to go to social media. Having said that, overall first contact via social media (43%) has fallen six points while the use of aggregators (11%) and alerts/notifications (10%) has grown. The mix of social networks has also shifted since 2016 with less use of Facebook and more of Twitter and Instagram. The pattern in Finland is similar to the UK, with Italy more like the United States, except that much of the social first use is for messaging apps like WhatsApp (8%).

Smartphones Grow Further; Rise of Mobile Aggregators

Smartphone sales may be slowing down but the previous section shows how our dependence on them for news continues to grow. Two-thirds of our combined sample (66%) now uses the smartphone for news weekly, with usage doubling in most countries over the last seven years.

People are still using computers and tablets for news but when we ask about preferred device the convenience and versatility of the smartphone tends to win out. In the UK the smartphone overtook the computer in 2017 and together with the tablet is now preferred by twice as many people. Tablet usage is stable, with a small group of older and richer users (16%) continuing to prefer accessing news via larger screens.

These trends matter for three reasons. First, it has become harder to make display advertising work on smaller screens and this is contributing to the financial difficulties for publishers. Second, content formats designed for the print/desktop era are becoming increasingly outdated on mobile displays, and third, personally addressable devices enable targeted content and experiences – putting a greater premium on those with access to more content and more data (primarily platform companies).

Mobile Aggregators Offer New Opportunities, But with Strings Attached

Against this background we are seeing a significant, if relatively modest, shift towards mobile news aggregators. Google News relaunched last year with a new design and greater focus on AI-driven recommendations, while mobile manufacturers running the Android operating system are integrating news aggregators like Upday, News Republic, and Flipboard into the core operating system, partly as a response to the success of Apple News.

It is hard to capture these trends accurately in a survey because respondents often see these as ‘news links on their phone’ rather than a distinct destination, but our qualitative research is giving us a clearer picture of the role these services play in news repertoires. Younger groups in particular love the convenience, the lack of friction, and the way it brings multiple brands into one place. We find some users actively curating and configuring the news that is most relevant to them but most are using them in a more incidental or passive way.

It’s just the one that comes with my phone. You get a notification on this bar here. Sometimes you find yourself on a website that you wouldn’t normally like to go on.

Chloe, 31–35, UK in-depth interview

I like using Apple News because it consolidates everything into one place and you don’t see five articles about the same thing.

Maggie, 21–24, US in-depth interview

Google News reaches 15% of our US sample, which is a similar level of weekly usage to the Washington Post. Reach for Apple News overall is just 10% but among iPhone users specifically, the news service now has higher reach (27%) than most US news websites. In the UK, a quarter of Apple smartphone users (24%) access news this way, which puts the service a clear second behind BBC News amongst this group.

It is important to distinguish between Upday, Google News, and Flipboard which pass traffic directly to publishers, and others like Apple News, and Yahoo! News which are trying to become destinations in their own right, republishing full stories in return for a share of advertising or subscription revenues. Mobile aggregators can bring reach and attention but with the latter category many publishers will be wary about the loss of control, the weakening of brand attribution, and lower revenue – with some platforms looking to take a cut of up to 50%.

It should be noted that mobile aggregation is already majority behaviour in many Asian countries. Yahoo! News reaches two-thirds (66%) of smartphone users in Japan each week, Naver reaches 73% of smartphone users in South Korea, while Line Today reaches 47% of our Taiwanese sample. Local mobile aggregators are also a force in Italy (Giornali, 17%), Norway (Startsiden, 18%), and Sweden (Omni 12%).7

Social Media and the Move to Messaging

It has been a dramatic year for social media with Facebook and YouTube under fire for spreading misinformation, encouraging hate speech and online harm – as well as playing fast and loose with our privacy.

Facebook’s response to these issues has already impacted news publishers through a series of algorithm changes, but the next step could be even more disruptive. In February, Mark Zuckerberg announced a shift of focus to more private messaging and has said that he expects WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger to be the main way that users interact across the Facebook network. This means that the sharing of news and comment in the future will be less open and less transparent.

The chart below, which averages data from twelve countries we have been tracking since 2014, shows the rapid growth for WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and newer networks like Instagram and Snapchat, which also incorporate private features like ephemeral messaging. By contrast reach for Facebook and Twitter has been flat. As more people use messaging services, news usage has also risen, while the relative importance of Facebook itself has declined.

It should be noted that Facebook as a company remains in a strong position. As owner of Instagram, Messenger, and WhatsApp its products reach 84% of our combined sample and 57% for news. Messaging apps, which also include Viber, Telegram, and WeChat, reach 75% for any purpose across our sample and 31% for news – up 8 percentage points from two years ago.

PROPORTION THAT USE EACH MESSAGING APP FOR NEWS

Selected markets

Base: Total sample in each market ≈ 2000.

This explosive growth of WhatsApp has so far been concentrated in Latin America, South East Asia, Africa, and Southern Europe – as well as in India,8 which we covered in a recent Reuters Institute stand-alone report focused on English speakers. Around half of our Brazilian (53%) and Malaysian (50%) samples use WhatsApp for news, compared with 9% in the UK, 6% in Australia, and just 4% in both the United States and Canada

The data and chart above capture just those countries covered in this report (and India), but other publicly available data confirm that WhatsApp use is more prevalent in the global south, countries where reliable information is often in short supply and public institutions are more fragile.

The spread of unfounded rumours has led to a spate of killings in India while our country page reports from Brazil and South Africa illustrate how politicians have used the network to spread negative stories about opponents in a way that would be harder in open networks. Fact-checking organisations have set up ‘tip lines’, appealing to the public to flag illegal or dangerous content. In Brazil, roughly a million WhatsApp groups were created to promote candidates in the recent elections including far right former army captain Jair Bolsonaro, who was initially starved of coverage via TV. Facebook itself has belatedly invested in collaborations with fact-checkers, digital literacy campaigns, and has made it harder to share messages within WhatsApp.

The spread of misinformation often happens via groups that are set up specifically to discuss politics. These are common in WhatsApp, mainly in developing countries, but have also become a greater focus in Facebook itself, which recently prioritised these posts in the newsfeed. Facebook Groups have come under scrutiny for their role in co-ordinating the recent Yellow Vest (Gilets Jaunes) protests in France. But how many people use Facebook Groups and how do these differ from the way people use groups in WhatsApp?

This year, we explored these questions in detail across nine countries and found that although half of Facebook users (51%) have joined some kind of public group, only a minority use them for news and politics (14%). That figure rises to 22% in Brazil and 29% in Turkey. The majority of Facebook Groups are for non-news subjects including gardening or sport (22%), news about the local community (18%), and parenting (7%).

By contrast we find that WhatsApp is primarily used for private groups, most often with friends and family or workmates. News may come up in discussions but is not the primary purpose.

Behind the averages, we find a marked difference in the way WhatsApp groups are used across countries. In Brazil, almost six in ten WhatsApp users (58%) take part in groups with people they don’t know, compared with just over one in ten (12%) in the UK. Almost a fifth (18%) discuss news and politics in a public WhatsApp group in Brazil compared to just 2% in the UK, potentially increasing the chances of misinformation being spread. We find that people who used groups in WhatsApp and Facebook have lower trust in the news and are more likely to use partisan news sites.

People Spending Less Time with Facebook, More with Instagram

Further evidence of the changing shape of social media comes in a new survey question we asked about how much time people spend with each social network or messaging app.

The picture in the UK is typical of many Western countries and shows that many people are spending less time with Facebook and more time with Instagram and WhatsApp. We have calculated figures in the next chart by subtracting the proportion that say they spent less time from the proportion that say they spent more. For example, almost half (46%) of under 35s in the UK said they spent more time with Instagram in the last year but 14% said they spent less. The net difference is +32%.

Younger groups in many countries seem to be swapping Snapchat for Instagram, which has become, for many, the ‘go-to’ social network. This year’s depth interviews confirm that young people are spending less time with Facebook, even if they are not abandoning it altogether.

I think I used to use Facebook a lot, and over past five, six years, I basically hardly use it at all now, which is one massive change. In its place, Instagram has come,

Chloe, 31–35, UK in-depth interview

PROPORTION THAT USED INSTAGRAM AND SNAPCHAT FOR NEWS

Base: Total sample in each country ≈ 2000.

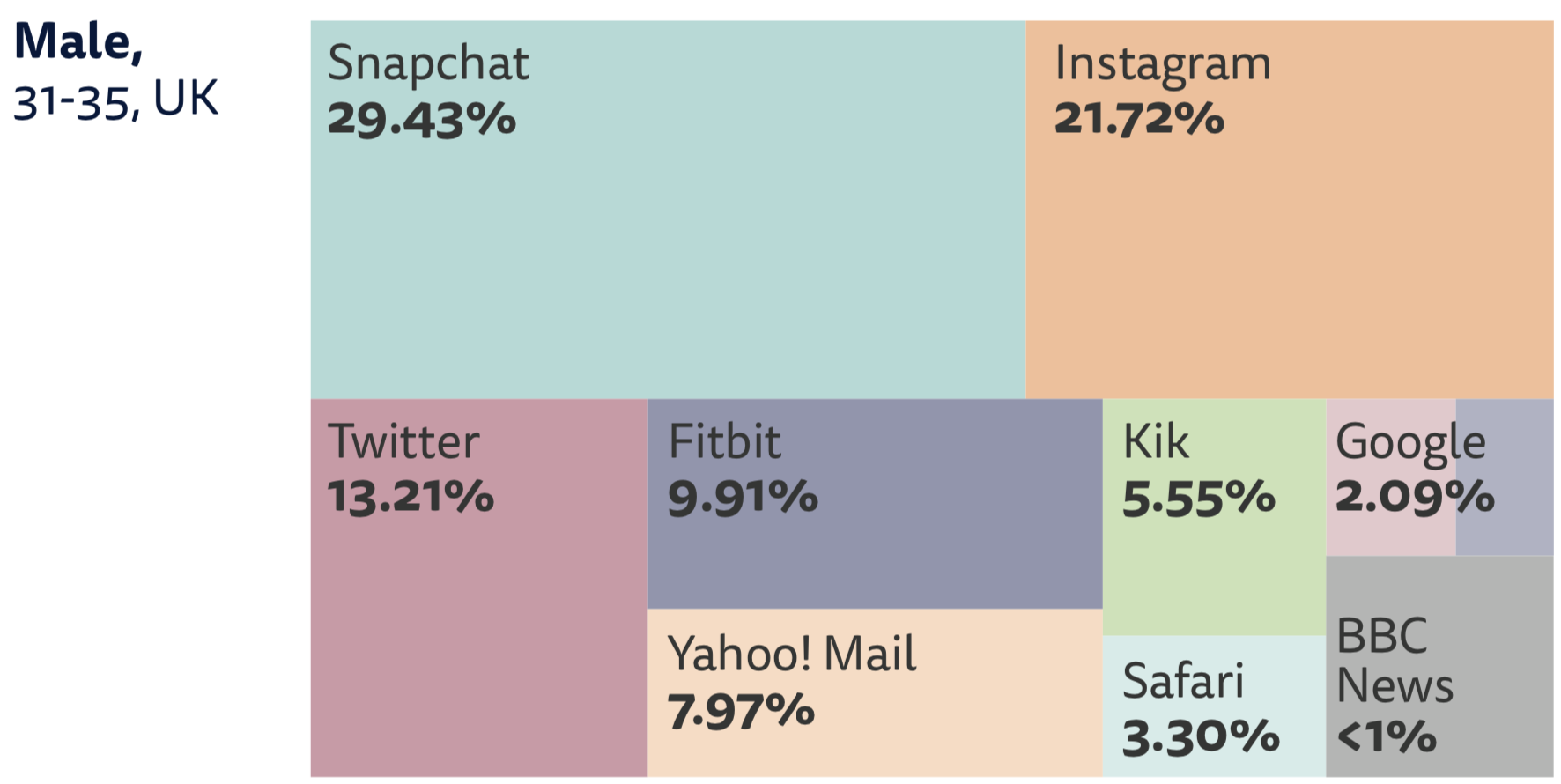

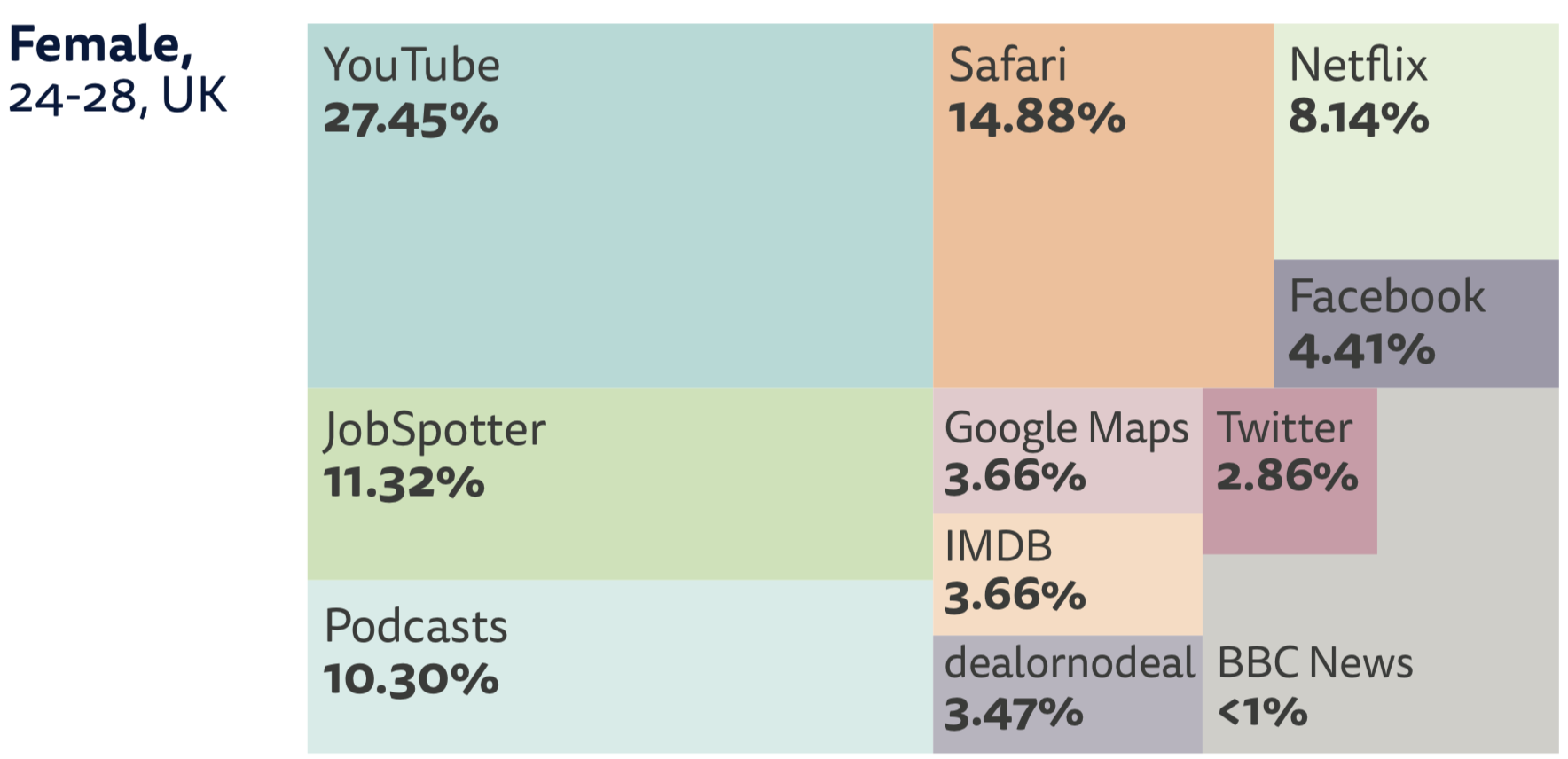

We were able to get further insights into the behaviour of younger groups in the US and UK (so called Gen Z and Gen Y) by tracking the amount of time they spent on different mobile apps and websites over a ten-day period.9 This reveals the overwhelming importance of social media and communications to these younger groups. In these time charts (see below) taken from the mobile phone usage of two of our respondents, notice the relatively little time spent within Facebook compared with Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat, and even Twitter.

PROPORTION OF TIME SPENT WITH DIFFERENT MOBILE APPS

Two individual respondents over 10 days

It is striking that communication, social media, and web-browsing apps dominated the time spent for all 20 young people tracked as part of our study. This shows the importance of finding ways to bring at least some news to social platforms if younger groups are to be engaged. In both illustrated cases, less than 1% of time was spent with BBC News, the most popular news app.

Trust and Attitudes to the News Media

Overall trust in the news is down 2 percentage points (all market average) from 44% to 42%, with trust in the news people use themselves falling below 50%. Trust in the news found in distributed environments, like social media (23%) and search (33%), is even lower but is largely unchanged from last year.

PROPORTION THAT TRUST MOST NEWS FROM EACH MOST OF THE TIME

All markets

Base: All markets: 75,749

At a country level, we continue to find stark differences. The media remain broadly trusted in Finland (59%), Portugal (58%), and Denmark (57%), while less than a third say they have confidence in the news in Hungary (28%), Greece (27%), or Korea (22%). In many of these countries the media are not considered to be sufficiently independent from political or business elites.

Specific events clearly have affected trust in a number of countries this year. Trust is down 11 points in Brazil after the recent fractious election, but perhaps the biggest surprise is a 11-point fall in trust in France from 35% to 24%, driven by the partisan nature of the Yellow Vest protests. Some journalists were attacked – sometimes physically – for not representing the protestors and being part of the establishment.10 But lower trust does not necessarily mean lower usage. 24-hour news channel BFM achieved some its highest ever ratings at the same time as showing a significant fall in trust scores (5.9 to 4.9 on a ten-point scale).

Major upheavals like the Yellow Vests or Brexit in the UK have put a strain on perceived impartiality of the news media, which in turn can affect trust. But if we look over time across some of our biggest countries, we see a generalised – and worrying – picture of decline. Even countries like Finland and Germany, which have not seen dramatic polarising events, have seen falls of 9 and 13 percentage points respectively in just five years. Across the 12 countries we have been tracking since 2015, trust scores are down on average by 4 points though they have risen slightly in Italy, Spain, Australia, and Ireland and have remained level in the Netherlands and Denmark

It is also notable in the table above that trust levels in the United States (32%) have remained flat overall, but this hides a much richer and more dramatic story.

Digging into the detail, we find an increase in trust (+18pp) amongst those who self-identify on the left of the political spectrum as they lent their support to liberal media outlets in the wake of Donald Trump’s victory. Over the same period, we have seen the almost total collapse of trust on the right to just 9%.

In the UK, we don’t see the same picture. Trust on both the left and the right has fallen, but if anything the trust gap has narrowed – perhaps because both are equally unhappy about Brexit coverage, which crosses party lines. Whatever the reasons, there has been no total loss of confidence amongst those on the right.

Misinformation and Disinformation

More than half (55%) of our sample across 38 countries remains concerned about their ability to separate what is real and fake on the internet. Concern is highest in Brazil (85%), South Africa (70%), Mexico (68%), and France (67%), and lowest in the Netherlands (31%), and Germany (38%), which tend to be less polarised politically. The biggest jump in concern (+12pp) came in the UK (70%) where the news media have taken a lead in breaking stories about misinformation on Facebook and YouTube and there has been a high-profile House of Commons inquiry into the issue.

Impact of Media Literacy?

One consequence of this concern seems to be a greater awareness and affinity with trusted news brands. One positive finding of our report this year is that over a quarter (26%) have started relying on ‘more reputable’ sources of news – rising to 36% in Brazil and 40% in the US. A further quarter (24%) said they’d stopped using sources that had a ‘less accurate reputation’, with almost a third (29%) deciding not to share a potentially inaccurate news article. The interpretation of ‘reputable’, ‘less accurate’, ‘dubious’, and other subjective terms were left to respondents to determine.

PROPORTION THAT SAY THEY HAVE CHANGED ONLINE HABITS IN THE LAST YEAR

All markets

Base: Total sample = 75,749

Behaviour seems to have changed most in countries where concern about misinformation is highest. Almost two-thirds (61%) in Brazil said they had decided not to share a potentially inaccurate story in social media and 40% in Taiwan after recent elections marked by misinformation – compared with just 13% in the Netherlands, the country with the lowest level of concern in our survey. The shift to more reputable sources is a bit more evenly split.

We picked up similar sentiments in our qualitative research with younger groups in the UK and the US. Many of our respondents said that they were now paying more attention to the name of the brand when using social media. Others said they were calling out friends more often for sharing inaccurate news.

If I see something like New York Times, Bloomberg, Washington Post, I’m going to assume that it’s credible and valid but if I see something that’s on a news website that I’ve never heard of before, I’m more likely to question the source of the news.

Maggie, 21–24, US in-depth interview

I think I’m much more limited in the news that I access now, because of this… I think the ones that you trust are the traditional ones that have been around for a long time, like the BBC, like the Guardian, like the Independent.

Chloe, 31-35, UK in-depth interview

All this suggests that higher media awareness and digital literacy campaigns may be having some effect, though it should be noted that change has been more evident with the better educated who arguably may be less likely to be duped anyway. In the United Kingdom it is mainly younger groups that have modified their behaviour, while in the United States the biggest change has come with older demographics.

Alternative and Partisan News Websites

We have seen a continuing rise of populism in many countries and a further fall in trust in established media over the last year. At the same time, we find greater consumer literacy and changes to Facebook algorithms designed to damp down extreme and polarising views. But what has been the outcome of these conflicting trends on the reach of alternative and partisan news sites?

These sites are said to have played a part in bringing Donald Trump to power in the United States, reshaping decades of centrist politics in Sweden, and mobilising support for Jeremy Corbyn in the UK. Partisan sites should be distinguished from those that ‘deliberately fabricate the news’, even if they are often accused of exaggerating or tailoring the facts to fit their cause.

Examples are Breitbart and InfoWars in the United States (right-wing), Fria Tider in Sweden (right-wing), and the Canary and Evolve Politics in the UK (left-wing). Though ideology is a key motivator, some sites are also looking to make money, or at least break even, from these activities. The narrowness of their focus also separates them from established news sites like Fox News and Mail Online, which also have a reputation for partisan political coverage, but tend to cover the full range of news (world news, sport, entertainment).

Working with local partners we have identified a number of sites that matched our criteria and this year we have added sites in France and Brazil to our list.

The data below suggest that there has been little change in weekly usage of these sites in countries like the US, Sweden, and Norway where these sites are used by a significant proportion of the population. Even if social media algorithms are promoting these sites less, users and supporters are still finding ways to access them.

In all three countries we also see a large gap between awareness of these sites and actual usage, which suggests that their impact on the wider discussion is not just confined to users. As last year we also note wide variation in usage. Almost a quarter (22%) of our Swedish sample accesses one or more of seven partisan and alternative websites, and over half are aware of them – while these types of sites hardly feature at all in the Netherlands or Belgium. Even at a time of high tension in the UK over Brexit only 7% use one or more of these sites weekly compared with almost a quarter in the United States (22%).

Alternative and partisan sites elsewhere have a more diverse set of motivations. In France these include Russian state broadcaster RT which gave exhaustive and often uncritical coverage of the Yellow Vest protesters. RT France in particular was accused of spreading lies, specifically that the police had been siding with protestors. Our data suggest high awareness of both RT and Sputnik (10%) but relatively low usage (3% for each).

Populism and the Media

The growth of populism, for example in the UK and France, is putting enormous strains on left/right political party systems. But it is also raising new questions for journalists over how far to represent populist views, and how to satisfy a readership that no longer splits easily along traditional lines.

This year we have attempted to add a populist dimension to our study of media consumption by measuring responses to two questions; first, how distant respondents feel from their elected representatives and, second, how respondents feel about the people taking more important decisions directly. Putting these responses together we can create a group of people in each country with broadly populist attitudes and one with less populist attitudes.

One surprising finding is that populists prefer to use television news compared with non-populists and are less likely to prefer online news. These data will support those who argue that the role of social media has been overplayed when explaining the rise of Donald Trump – compared with the part played by supportive television networks like Fox News.

Populists in the United States are no less or more likely to use social media as a main source when compared with non-populists. However, they are more likely to share and distribute news in social media and take part in groups about news and politics. They tend to prefer Facebook, whereas non-populists gravitate towards Twitter.

We also find that in most countries (e.g.United States, Spain) left–right perspectives still have a bigger impact on media choices than populist attitudes. But it is a different story in Germany and Sweden. Later in this report we explore this subject in more detail and map media usage against both dimensions.

News Avoidance and News Overload

In a world that feels increasingly uncertain, polarisation, misinformation, and low trust may not be the only issues facing the news industry. In our data this year we find that almost a third (32%) say they actively avoid the news – 3 points more than when we last asked this question in 2017. This may be because the world has become a more depressing place or because the media coverage tends to be relentlessly negative – or a mix of the two.

News avoidance is highest in Croatia (56%), Turkey (55%), and Greece (54%). It is lowest in Japan (11%) where reading the news is often seen as a duty.

Brexit Blues

In the UK, news avoidance has grown 11 percentage points mainly due to frustration over the intractable and polarising nature of Brexit. Here, over half (58%) of respondents said the news had a negative impact on their mood, while four in ten (40%) said there was nothing they felt they could do to influence events. When asked about the type of news avoided, more than two-thirds (71%) cited Brexit coverage, followed by other types of politics (35%), and then sports news (28%). The majority of open-ended responses also mentioned frustration or sadness over Brexit.

Those who voted to remain in the EU, including the young and those in London, who avoided the news were more likely to say that news has a negative impact on their mood.

Although I do watch the political news avidly, I made a new resolution to stop as it has a negative effect on my mood as I feel powerless to change anything.

Female 55+, UK

Leave voters were more likely to avoid the news because they can’t rely on the news to be true. In many cases this is because they believe that the news is biased or partial in some way.

Brexit has been rammed down our throats for couple of years plus most of them are biased towards us staying in the EU.

Male 55+, UK

News Overload

Others still (28%) agree that there is too much news these days, which partly reflects the way in which constant news updates and different perspectives can make it hard to know what is really going on. A common complaint is that users are bombarded with multiple versions of the same story or of the same alert. ‘[There is] too much conflicting and confusing news’, said one respondent to our UK survey. Perception of overload is highest in the United States (40%), where even the president adds to the noise with regular tweets. It is lower in countries with a smaller number of publishers like Denmark (20%) and the Czech Republic (16%).

Evaluations of the News Media

In this age of greater turbulence, complexity, abundance, and competition, how is the news media doing in meeting expectations of its role in society?

This year we asked respondents to evaluate the performance in five areas: whether they think the news media focuses on the right topics, helps them properly understand current events, keeps them up to date, uses the right positive/negative tone, and does a good job of monitoring and scrutinising the powerful.

Across all countries, most people agree that the news media keeps them up to date with what’s happening (62%), but only half (51%) say news media help them understand the news. Just four in ten (42%) think that the news media does a good job in its watchdog role – scrutinising powerful people and holding them to account. These qualities – of explanation and scrutiny – are at the very core of the mission of journalism in many countries, and these scores speak directly to declining trust in the news.

PROPORTION THAT AGREED WITH EACH ATTITUDE TOWARDS THE NEWS

All markets

Base: Total sample = 75,749.

There are interesting country differences in terms of these attributes. News organisations in rich, Northern European countries like Finland (51%) and Norway (51%) tend to have the best reputation for holding rich and powerful to account. By contrast media in nations such as Hungary (20%) and Japan (17%) are seen to be doing a poor job in this regard.

PROPORTION THAT AGREED THE NEWS MEDIA MONITORS AND SCRUTINISES POWERFUL PEOPLE AND BUSINESSES – SELECTED MARKETS

Base: Total sample in each market ≈ 2000, Taiwan = 1005.

Even in countries with the highest reputation we find a significant gap between journalists’ own perceptions about how well they are doing their job and the views of news consumers. Further international comparisons are explored later in this report.

Looking at the two other dimensions in our survey, we find surprisingly little criticism of the media’s agenda-setting role, with only a minority (25%) feeling that the topics selected are not relevant to their lives. There seems to be more of a problem with the tone taken by the news media to those stories. Four in ten (39%) think that the news media take too negative a view of events. This is a complex statistic to interpret, not least because a difficult or ‘negative’ press is often the flip side of robust scrutiny. It may be no coincidence, for example, that a country like Singapore has the least negative media (22%) but also scores poorly in term of robust scrutiny (32%). But elsewhere it is interesting to note that many countries that have the best reputation for holding the powerful to account (Finland, Netherlands) are also seen as least negative (23%). Equally, many countries where the news media have a poor watchdog record are seen as having the most negative press (Greece 59%, Bulgaria 52%).

These themes around the negativity of the news media also came out strongly in our in-depth interviews with young people this year in the US and UK. In the US, the idea of negativity was often associated with perceptions that a negative or unfair agenda was being pursued by a publication (against Donald Trump or Serena Williams for example). In the UK, many of our interviewees felt that some (popular) media outlets simply had an unconstructive mindset:

The Daily Mail. They are always on social media, trying to make someone look bad.

Ellie, 18–20, UK

News is a major negative and has a huge impact on everyone who watches it. There is never any positive or happy news.

Female respondent, 24–35, UK

Broken News?

Along with the earlier evidence that some people are avoiding the news or are worn out by the amount of news, these kinds of data have fuelled new initiatives around ‘slow News’ (De Correspondent, Zetland, Republik, Tortoise Media,) and constructive or solutions-based journalism (HuffPo, BBC World Hacks). The founders of these initiatives argue that traditional news models and approaches are broken and they are looking to respond with more meaningful, inclusive, and less relentlessly negative coverage – often developed in closer collaboration with audiences.

At the same time, other media companies are looking to respond to the gap identified here between updatedness and understanding. Vox Media has built a formidable reputation for explanatory journalism, an approach that works particularly well with younger people looking to understand complex issues. Many traditional media companies have adopted similar approaches (BBC Reality Check).

Others are looking to attract young people through a less traditional agenda, often using new formats and voices (BuzzFeed, Vice).

Pivot to Audio Picks up Pace

Podcasts have been around for many years but these episodic digital audio files appear to be reaching critical mass as a consequence of better content and easier distribution. Over a third of our combined sample (36%) now say they have consumed a podcast in the last month – up from 34% in 2018 – with almost one in six (15%) saying they have consumed one about news, politics, or international news.

The Guardian, Washington Post, Politiken, AftenPosten, The Economist, and the Financial Times are amongst dozens of publishers to have launched daily podcasts in the last year. This follows the runaway success of the Daily from the New York Times, which has around 5m daily listeners, is rebroadcast on public radio, and is about to get a video spin-off series. Meanwhile the BBC has rebranded its on-demand radio app as BBC Sounds to reflect the shift to on-demand consumption and the growing interest of the podcast generation.

In the UK, younger age groups, who spend much of their lives plugged into smartphones, are four times more likely to listen to podcasts than over 55s – and much less likely to listen to traditional speech radio. Under 35s consume half of all podcasts despite making up around a third of the total adult population.

The core appeal of podcasts is the ease of use, and the ability to listen while doing something else. But for younger users podcasts also provide more authentic voices and the control and choice they’ve become used to.

With radio you can’t control what shows are on, whereas podcasts you can

Mark, 31–35, US

You’re not actively searching something or reading a screen. You’re letting it wash over you.

Chloe, 31–35, UK

In terms of location, younger people are more likely to listen when out and about, while older groups often access podcasts in bed when having difficulty sleeping – as well as when walking the dog or doing the chores at home.

But the age of innocence could be over as money starts to trickle into podcasts. Advertising is becoming more intrusive; Spotify and other platforms have started to pay publishers for premium content (blockbusters), and some news organisations like Politiken have started to restrict some of their daily briefings to subscribers only. This new money has brought more professional content and higher production values, but some fear that the purity and authenticity of the podcast experience could be lost in the process.

Usage of Voice-Activated Speakers Doubles Again, But News Usage Remains Disappointing

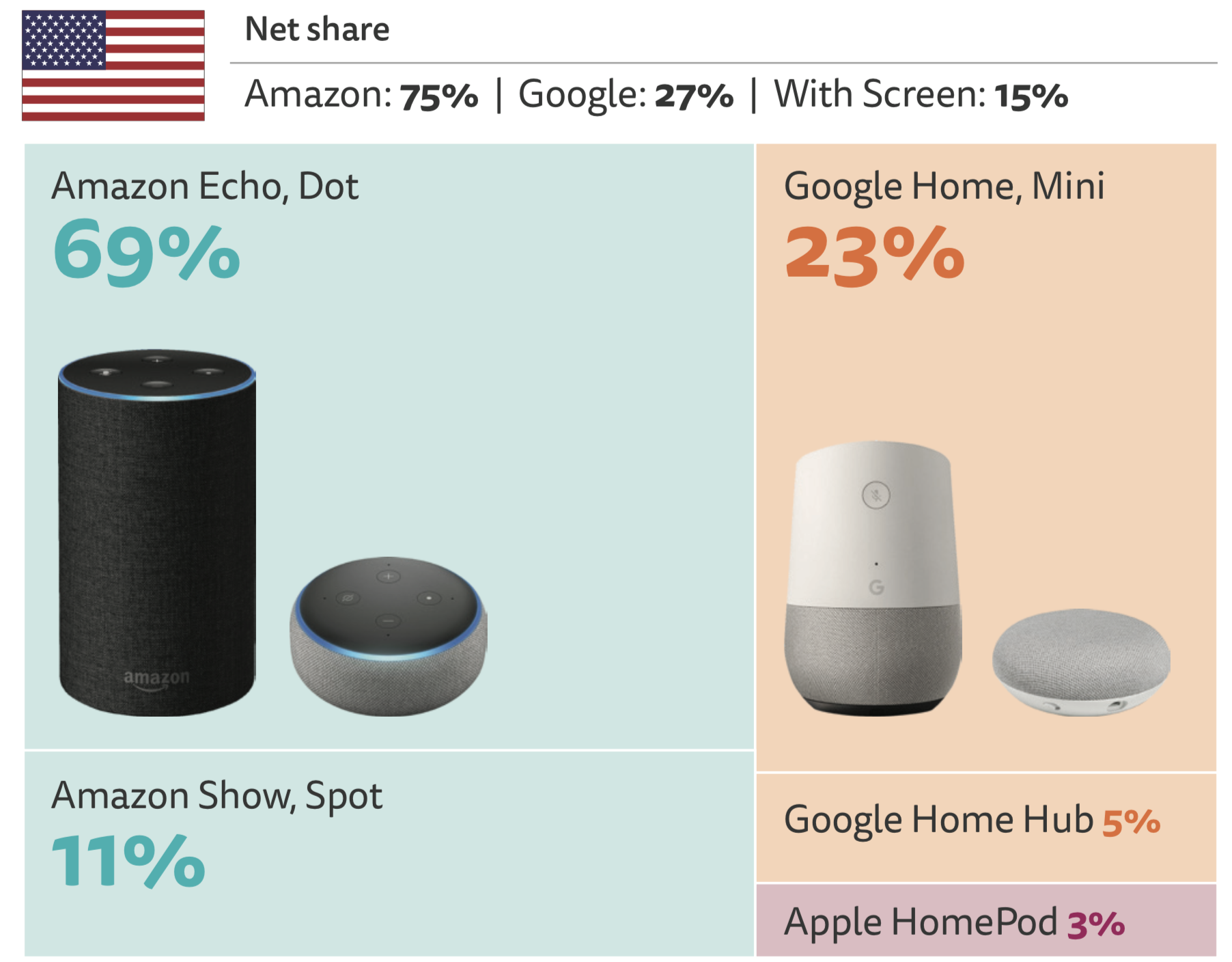

Audio prospects may be further boosted by the rapid adoption of voice-activated speakers such as the Amazon Echo and Google Home. Reach for any purpose has grown from 7% to 14% in the UK over the last year, from 9% to 12% in the United States, and from 5% to 9% in high-tech Korea. However, the proportion using smart speakers for news is declining as mainstream audiences come on stream. Less than four in ten access any news via their device in an average week in the US (35%) and UK (39%) and just a quarter in Germany (27%) and South Korea (25%).

Over the last year, both Google and Amazon have launched in a range of new markets including India, Spain, Mexico, and a number of Nordic countries.

Amazon still has a dominant position in the US, UK, and Germany but Google leads in a number of markets where it launched first, including Australia and Canada. Devices with screens like the Amazon Show and Spot have so far made little impact, with our research suggesting that the last thing most consumers want is more screens in their lives.

PROPORTION OF SMART SPEAKER OWNERS THAT USE EACH DEVICE

USA and Australia

Base: USA = 273, Australia = 161.

The issue of platform power is likely to become an increasingly important issue for publishers over the next year as Google and Amazon look to provide more aggregated news services in voice. But many are wary about helping to build value for platforms – again – without any path to monetisation.

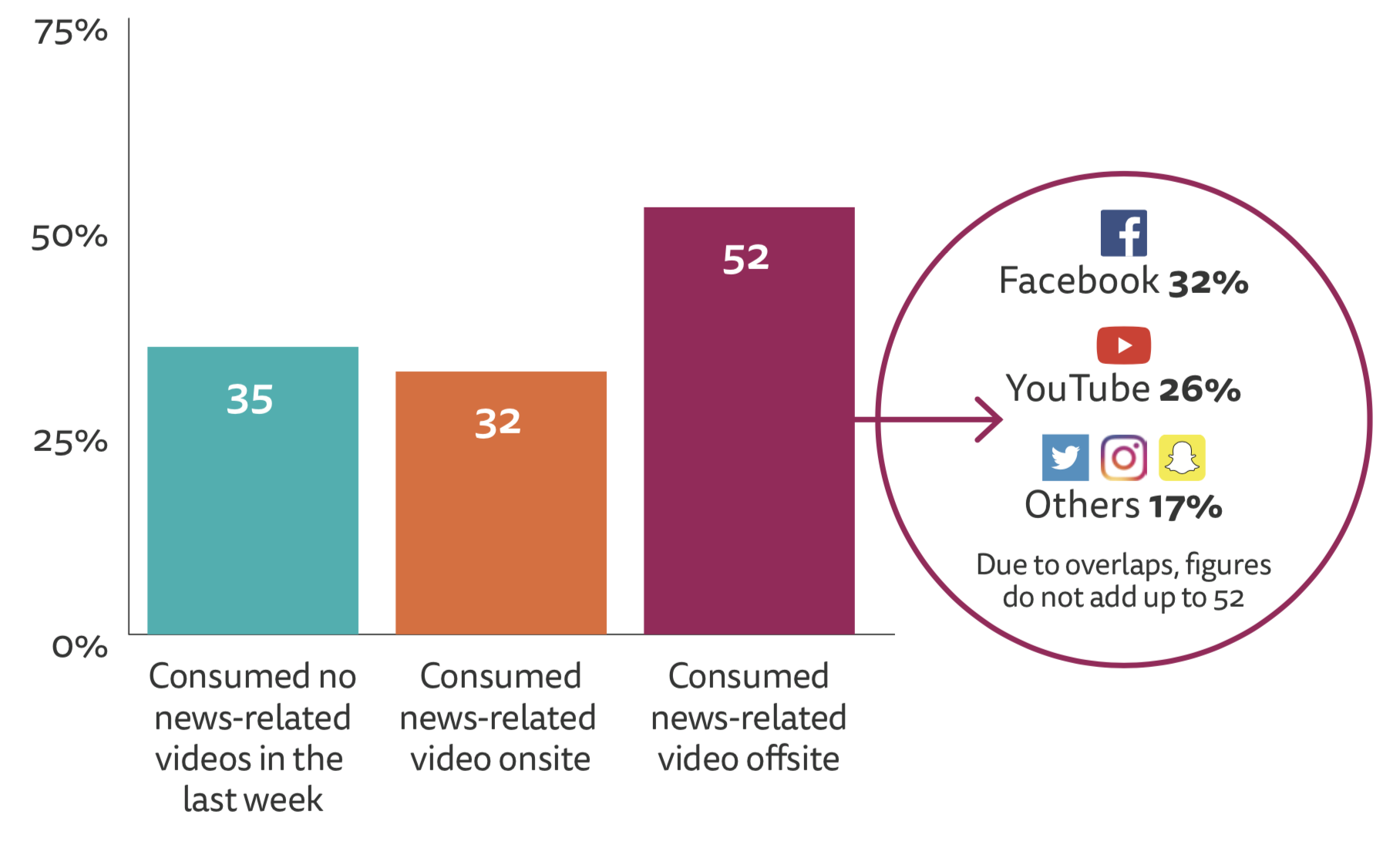

Video News Changing Shape

Video is a case of platform power writ large. Most video news consumption takes place on Facebook (32%) and YouTube (26%), where the context and monetisation rules are set by the tech companies. Over the last year Facebook has become a little less important for news video, with other platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat becoming a little more important (+3).

OFFSITE VS ONSITE NEWS VIDEO CONSUMPTION – ALL MARKETS

Short form video (straight news clips or crafted with music and subtitles) remains the most popular format for news but this has become increasingly hard for publishers to monetise. Facebook has switched its focus towards longer, scripted current affairs shows for Facebook Watch. Netflix and HBO have now joined the competition for this longer form content with significant amounts of money changing hands. Explained from the US publisher Vox is one long-form news series that has been recommissioned by Netflix for a second series.

It is worth pointing out that more than a third (35%) of our combined sample does not consume any online news video in an average week, a figure that rises to 54% in the UK and Germany. Platforms like YouTube have become an important centre of opposition media in Turkey, with 83% of our urban sample saying they have consumed news via offsite platforms. The vast majority (68%), across all countries, still say they prefer to consume news in text, though a significant minority of under 35s (13%) say they prefer to consume news in video.

Conclusion

This year’s report sees the news industry at yet another crossroads. Publishers are pushing hard to distinguish high-quality journalism from the mass of information that is now published on the internet – and more and more of them are looking to charge for that difference. Some traditional brands may be helped by concerns about misinformation, which mean that people are once again paying more attention to ‘reputable’ brands– even as others continue to complain about media bias and negativity. There is no sign that the majority of people are about to pay for online news, although many recognise that information on the internet is often overwhelming and confusing. Younger audiences in particular don’t want to give up instant, frictionless (and ideally free) access to range of diverse voices and opinions. They don’t want to go back to how the media used to be.

Some of the biggest brands have already shown they are able to attract a large number of paying subscribers, but the road ahead will be more challenging for other publishers. Loyalty and the ability to forge direct connections will be critical, as our data clearly indicate, but this will be hard to achieve just through the desktop or mobile web where news access tends to be fleeting and distracted. That’s why publishers are showing such interest in podcasts, longer form video, and even live events – more immersive formats that allow a brand personality to be expressed more fully while maintaining the choice and control demanded by a younger generation.

Wider changes are also in the air as subscription-based bundled businesses like Netflix, Spotify, Amazon (and now Apple) edge into the news market. Even Facebook has floated the idea of a dedicated news tab where content might be paid.11 But the relationship with these subscription players is unlikely to be any easier than with existing ad-focused models we’ve been used to. Platforms will want to take a substantial cut in revenue in return for distribution and will ultimately own the relationship with the customer. Established forms of distributed discovery like search and social media continue to be important, but newer platform products and services such as private messaging, mobile aggregators, and voice systems are starting to make an impact too. It is a crucial question whether publishers can in fact use these new platform services in ways that are mutually beneficial and deliver sustainable returns for publishers.

Despite the greater opportunities for paid content, it is likely that most commercial news provision will remain free at the point of use, dependent on low margin advertising, a market where big tech platforms hold most of the cards. This is where competition for attention will be most acute, where journalistic reputation will be most at risk, and where diversified revenue streams and smart strategies will be most critical for survival.

A number of media companies are unlikely to make this difficult transition. Many news publishers are stuck in a vicious cycle of declining revenue and regular cost cutting – as illustrated within our country page section this year. We also find some governments – increasingly alarmed by market failure, especially in local news and investigative journalism – considering using public money and other measures to support public interest journalism. Elsewhere, we find authoritarian-minded politicians looking at the weakness of commercial media as an opportunity to capture or unduly influence the media. These trends continue to play out at different paces in different places with no single path to success. Media users all over the world continue to flock to digital websites and platforms, and engage with many kinds of journalism online and offline. But we are still some way from finding sustainable digital business models for most publishers.

- https://schibsted.com/news/schibsted-will-be-divided-into-two-companies/ ↩

- Business Insider online poll conducted by Dynata, Feb. 2019 https://www.businessinsider.com/only-a-few-publishers-will-be-able-to-sell-subscriptions-at-scale-2019-3 ↩

- https://thenewpublishingstandard.com/scribd-nyt-subscription-deal-swedens-bookbeat-ties-bundled-deal-dagens-nyheter-storytels-rivals-challenges-ahead/ ↩

- https://www.recode.net/2018/8/9/17671000/new-york-times-trump-subscribers-news-slower-growth ↩

- https://www.recode.net/2018/8/9/17671000/new-york-times-trump-subscribers-news-slower-growth ↩

- Tow Center report on mobile alerts, Dec. 2018: https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/newsrooms-view-mobile-alerts-as-standalone-platform.php ↩

- Omni is owned by the publisher Schibsted. ↩

- India Digital News Report, Mar. 2019: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/india-digital-news-report ↩

- With the permission of the participants, we added tracking code to the mobile phones of around 20 young people in the US and UK so online behaviour, time spent, and specific news journeys could be measured. ↩

- https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-france-protests-press/french-media-denounce-violent-yellow-vest-attacks-on-press-idUKKCN1P70J5 ↩

- Facebook may pay publishers to put their stuff in a dedicated news section (Recode, 1 Apr. 2019) https://www.recode.net/2019/4/1/18290330/facebook-news-tab-mark-zuckerberg-license-fee-axel-springer-mathias-dopfner ↩