Executive Summary

In this report, we examine how public service media in six European countries (Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and the United Kingdom) are delivering news in an increasingly digital media environment. The analysis is based on interviews conducted between December 2015 and February 2016, primarily with senior managers and editors as well as on survey data from the Reuters Institute Digital News Report.

We show the following:

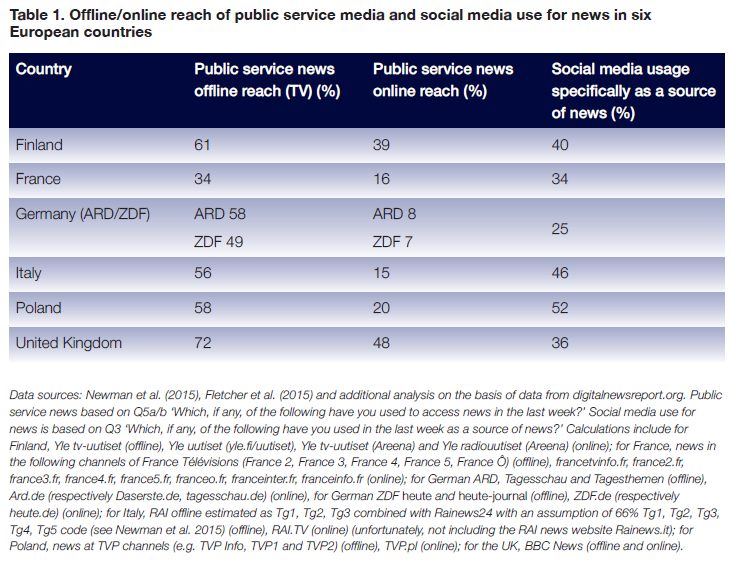

- Public service media organisations have high reach for news offline (via television and radio) in all six countries, but only in Finland and the United Kingdom do they have high reach for news online.

- In all countries but Finland and the United Kingdom, significantly more people get news online from social media than from public service media.

- Our interviewees highlight three particularly important issues facing public service news provision online today, namely:

- how to change organisations developed around analogue broadcasting media to effectively deliver public service news in an increasingly digital media environment;

- how to use mobile platforms more effectively as smartphones become more and more central to how people access news;

- how to use social media more effectively as more and more news use is driven by referrals and in some cases consumed off-site on platforms like Facebook.

- Public service media organisations in all six countries have faced, and continue to face, serious challenges to their ability to effectively deliver public service news online. These include internal challenges around legacy organisations’ ability to adapt to a rapidly changing media environment and the constant evolution of new digital technologies, but also external economic and/or political challenges.

- Across the three areas of organisational change, mobile delivery, and use of social media platforms, the British BBC and the Finnish Yle are generally seen as being ahead of most other public service media organisations. (Though they too are still heavily invested in their traditional broadcasting operations and need to continue to change to keep pace with the environment.)

- We identify four external conditions and two internal conditions that these two relatively high-performing organisations have in common. The four external conditions are: (1) they operate in technologically advanced media markets; (2) they are well-funded compared to many other public service media organisations; (3) they are integrated and centrally organised public service media organisations working across all platforms; (4) they have a degree of insulation from direct political influence and greater certainty through multi-year agreements on public service remit, funding, etc. The two internal conditions are a pro-digital culture where new media are seen as opportunities rather than as threats and senior editorial leaders who have clearly and publicly underlined the need to continually change the organisation to adapt to a changing media environment.

- The need for public service news provision to evolve will only increase as our media environments continue to change and digital media become more and more important. Addressing the external conditions for the evolution of public service media is a matter for public discussion and political decision-making. Developing the internal conditions, however, is the responsibility of public service media themselves, and a precondition for their continued relevance in a rapidly changing media environment.

This report is the first of a series of annual reports that will focus specifically on how European public service media are adapting to the rise of digital media, a series of reports that will over time cover more countries and more issues than those discussed here.

Introduction

All public service media in Europe aim to produce high-quality content, make it available across widely used devices and platforms, and reach all audiences. How they do it, however, varies – especially when it comes to digital media. In this report, we focus on how public service media in six European countries are dealing with three issues concerning public service news provision today:

- how to change organisations developed around analogue broadcasting media to effectively deliver public service news in an increasingly digital media environment;

- how to use mobile platforms more effectively as smartphones become more and more central to how people access news; and

- how to use social media more effectively as more and more news use is driven by referrals and in some cases consumed off-site on platforms like Facebook.

The countries we cover in the report are Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and the United Kingdom. Together, they represent a range of different European media systems, levels of technological development, and public service media traditions. 1

The focus of the report is on the intersection between technological change and public service news provision. It is important to underline that public service media confront these challenges and opportunities while also facing economic and political challenges in some countries. The move towards an ever-more digital media environment has been accompanied by debates around the role and remit of public service media as well as discussions of how public service is best delivered today. 2

Economically, funding for public service media has decreased in recent years in several countries, including France, Italy, and the United Kingdom, in part due to wider austerity measures and in part due to reductions in funding directed specifically at public service media. These pressures can be illustrated by recent cuts at the BBC in the UK and reduced funding for the Italian RAI and Polskie Radio.

Politically, a range of private media and some political parties are questioning the current scale and scope of public service media and calling for more narrowly defined roles and remits. These pressures include the ongoing legal battle between the German ARD and a range of newspaper publishers over what German public service media are allowed to do online and via apps for smartphones and tablets. 3 Simultaneously, governments in some European countries are putting public service media under more pressure and in some cases drastically reducing public service media’s independence from the state (EBU 2013; Arriaza Ibarra et al. 2015: 2). In January 2016, for example, the Polish president Andrzej Duda signed into law a bill handing the government control of public service media in Poland. Under the new law, senior figures in both Telewizja Polska (TVP) and Polskie Radio (PR) will be appointed and dismissed by the treasury minister rather than by the National Broadcasting Council, as was previously the case. 4

The report is based on interviews conducted between December 2015 and February 2016 with 36 people, primarily senior managers and editors at public service media organisations, as well as people with expert knowledge about the media in each country (see list of interviewees in the appendix). The interviews largely focused on how the respective public service media organisations are adapting to the rise of digital media, but also included discussions of wider economic and political challenges confronting public service media in the countries covered.

Our primary focus is on how public service media organisations in the six countries handle the challenges and opportunities represented by the rapid rise of digital media. We show that public service media organisations are adapting to the new environment at different speeds, and that some are falling behind because they are changing more slowly than the environment in which they operate and the public that they serve. Across the six countries covered, the British BBC and the Finnish Yle both reach large audiences with their online news and both have continually carried out substantial organisational reforms to adapt to an environment that continues to change quickly. The remaining public service media organisations have more limited reach with their online news and their organisations continue to be largely structured around traditional broadcast platforms.

The differences in performance and pace of change can be attributed in part to external economic (levels of funding) and political (remit of digital public service provision) factors. But it is clear that internal organisational barriers also constrain the ability of some public service media organisations to seize opportunities and tackle challenges online (EBU 2014; Malinowski 2014). In contrast to private media adapting to technological change, public service media generally face fewer economic challenges (as the need to develop new revenue models is less urgent), more political challenges (as they are bound by regulation and existing audiences’ expectations), and a somewhat different set of organisational challenges (as a more secure funding situation both enables experimentation and reduces the immediate need to adapt).

Despite a preference for the term ‘public service media’ over the more traditional ‘public service broadcasters’, and a frequent insistence on their ambition to deliver public service across all platforms, even leading public service media organisations widely seen as digital innovators are still heavily invested in and shaped by their broadcasting legacy. In January 2016, James Harding, the BBC’s Director of News and Current Affairs, said that BBC News still invests more than 50% of its budget in linear television, about 40% in radio, and 7% in online media. (By comparison, in 2015, 41% of UK respondents in the Reuters Institute Digital News Report named television their main source of news, 10% radio, and 38% online media (Newman et al. 2015)). As Harding said: ‘We can’t afford to do everything. [This is] about setting our priorities. The choices we make now will determine the future.’ 5

The first challenge is trying to provide news for everyone, including hard-to-reach younger people. Across the countries covered here, public service media have high reach for offline news, very different reach online, and vary widely in their ability to reach especially younger people, with the BBC reaching about 68% of 18–24 year olds with news across offline and online platforms on a weekly basis in the UK, compared to 24% for ZDF in Germany.

The second challenge is moving from a digital strategy centred on desktop internet and personal computers to one focused on mobile devices. Across the countries covered here, between 27% (UK) and 14% (Poland) of online news users say that smartphones are the main device used for news consumption. Amongst younger people, the percentage is far higher, and the figure has been rising rapidly in recent years.

The third challenge is developing effective ways of delivering public service news via third-party platforms including search engines, social media, video-hosting sites, and messaging apps. Across the countries covered here, between 56% (Poland) and 23% (Germany) of online news users say they consume, share or discuss news via Facebook. Only in the UK do significantly more people use public service media for news online than use social media for news.

These three challenges are generally seen as closely linked in that more effective strategies for mobile news and use of third-party platforms are seen as key to reaching younger audiences and serving the whole population via all relevant channels. These challenges are also all seen as linked to an underlying issue of organisational change as most public service news provision is still structured primarily around legacy broadcast media rather than digital media.

Table 1 provides an overview of the performance of public service news offline and online in terms of audience reach in the six countries covered. Overall, public service media are amongst the most widely used sources of offline news in all six countries, but their online reach varies significantly and in some countries social media are by now more frequently named as a source of online news than public service media.

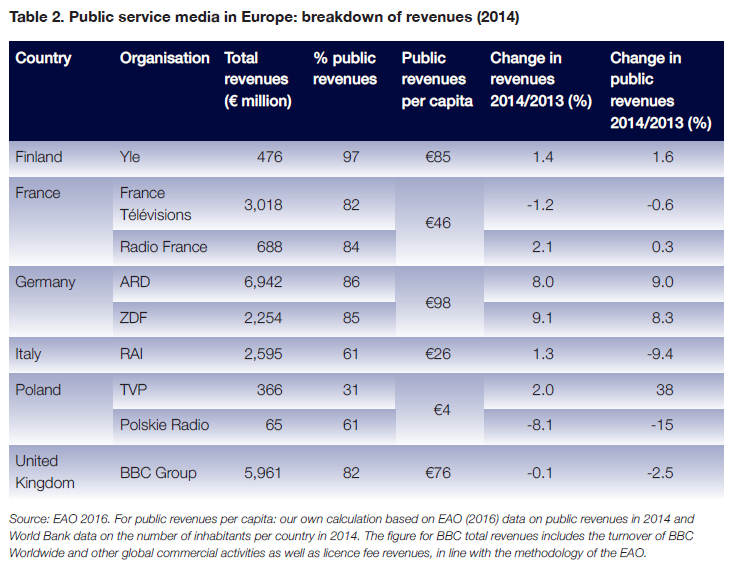

Table 2 provides an overview of the main national public service media organisations in each of the six countries, and their funding structure. Some of these are integrated public service providers which have always operated across platforms (radio, television, and now online). Others are separated by legacy platform (radio and television, each with their own online offerings). The funding levels vary, as do the commercially generated revenues, from a small fraction for the Finnish Yle to a majority of total revenues at the Polish TVP.

Table 2 provides an overview of the main national public service media organisations in each of the six countries, and their funding structure. Some of these are integrated public service providers which have always operated across platforms (radio, television, and now online). Others are separated by legacy platform (radio and television, each with their own online offerings). The funding levels vary, as do the commercially generated revenues, from a small fraction for the Finnish Yle to a majority of total revenues at the Polish TVP.

The next section provides a series of country profiles for readers who want more context on each country. These can be skipped by those who want to go straight to the main findings around organisational change, mobile news provision, and use of social media.

The next section provides a series of country profiles for readers who want more context on each country. These can be skipped by those who want to go straight to the main findings around organisational change, mobile news provision, and use of social media.

Public Service News in Europe: Country Profiles

Finland – Yle

The Finnish public service media organisation Yle is an integrated public service provider for TV, radio and digital. It is 99.9% state-owned and operations are financed by public broadcasting tax which replaced television licences at the beginning of 2013. Yle has a strong position in terms of television reach. In 2014, the Yle television channels had a total daily audience market share of 55% (EAO 2016).

When it comes specifically to news, 61% of Finnish respondents in the Digital News Report 2015 stated that they had watched Yle TV news in the last week. This means that Yle is the most widely used offline source of news in Finland. Online, Yle also has a strong position with 39% saying they use various Yle sites for news, but Yle has lower reach than the website of two tabloid newspapers Illta-Sanomat (55%) and Iltalehti (51%) (Newman et al. 2015; see Table 1).

Smartphone use is high in Finland. Almost one in four respondents said smartphones are their main way of accessing news online. Social media were used by 40% of respondents specifically as a source of news in the last week (see Table 1). Facebook is the most widely used social media platform for news in Finland, followed by YouTube (Newman et al, 2015).

Since 2013, the Finnish public service media organisation Yle has been tax-funded. In contrast to the flat licence fee before 2013, the tax is income-adjusted. All individual adults pay a flat income tax earmarked for Yleof 0.68% up to a maximum of €140 per year. The lowest paid, those earning less than €7,352 a year are exempt from paying the tax.

At €85 per capita, Finland has the second highest level of public service funding of all the countries covered here, and with 97% of Yle’s €476m budget coming from public funds, it has the lowest level of commercial funding of public service media (EAO 2016, see Table 2).

France – France Télévisions and Radio France

French public service media consist of two main separate organisations, one built around TV and one around radio: France Télévisions and Radio France. 6 Both are state-owned companies and funded by the revenues from a licence fee, additional state funding as well as commercial revenues. Policies on French public service media have been characterised by a strong government influence in the past (see Brevini 2013).

In France, public service media also have a fairly strong position in terms of television audience share. Combined, the main French public channels in 2014 together accounted for about one-third (30%) of daily viewing (EAO 2016).

For news, commercial television is the most widely used offline source. according to the Digital News Report 2015, the private channels BFM TV and TF 1 are the leading sources of news offline. both have 43% of French respondents saying they have used them in the last week. France Télévisions by comparison reaches 34%. Online, the most widely used brands are prominent national newspapers like the websites of the free daily 20 Minutes (12%), Le Monde (11%) and Le Figaro (10%) as well as digital – only offerings from Google News (11%) and Yahoo (8%). The public service media websites (FranceTV info and the various domains of France Télévisions) are used by a combined 16% of respondents as a source of news (Newman et al. 2015; see Table 1).

The smartphone is increasingly important for how people in France access news. A quarter said it is their main way of accessing online news. Social media are also important with 34% of respondent using them specifically as a source of news. Facebook is the main social media platform for news, followed by Youtube (Newman et al. 2015).

French public service funding is, at €46 per capita, significantly lower than in Finland, Germany, or the United Kingdom, but considerably higher than Italy or Poland. France Télévisions’ total revenues for 2014 were €3,018m, of which 82% came from public funding and the rest from commercial sources. Radio France revenues were €688m, and 84% came from public funding (EAO 2016; see Table 2). The majority of the funds for public service media in France comes from a household licence fee of €137 per annum, with some additional funding provided by the state.

in germany, public service media structure reflects the federal political structure. there are two main national public service broadcasters: ard (founded in 1950) and ZdF (only tv, founded in 1963), as well as deutschlandradio, a national public service radio broadcaster (founded in 1994) which co-operates with ard and ZdF. ard consists of nine regional public service broadcasters. between them they all operate their own regional television channels, some in co-operation with others, and all of them have their own radio channels. together they collaborate on national programming for the so-called ‘first channel’ (das erste). in addition to this, the international service deutsche welle (dw) (founded 1953) is also a member of ard, but not covered here. in contrast to the ard’s complex federated structure, ZdF (Second german television) is established by all 16 states and serves a national audience.

Germany – ARD and ZDF

Together, the German public television channels accounted for a total daily audience share of 45% in 2014 (EAO 2016). when it comes to news, the national public service evening news bulletins still draw a large audience. In the Digital News Report 2015, 52% of German respondents said in the last week they had watched the main ARD news programme Tagesschau and 38% named ZDF’s flagship news programme heute. In comparison, RTL Aktuell, from the private broadcaster RTL, reached 36% of respondents weekly. Despite their offline strength, however, German public service media have only limited reach online. The main ARD online news offerings were used by 8% and ZDF.de by 7% (see Table 1). The site of the national news magazine Spiegel Online (16%), the portal t-online (13%), and the main tabloid newspapers Bild.de (11%) all reached more people online (Newman et al. 2015).

Almost a quarter of German respondents said the smartphone is their main way of accessing online news. Social media platforms are used by 25% of respondents specifically as a source of news on a weekly basis. Facebook is the most important social media site in terms of news, followed by Youtube (Newman et al. 2015).

Since 2013, all households in Germany have been paying a flat fee of €210 per annum. This fee has replaced the old GEZ radio and TV fee, which was paid per device. The fee is still defined as a ‘broadcasting contribution’ (Rundfunkbeitrag) and not a public service contribution.

Public funding for public service media amounted to €98 per capita in 2014 in Germany, the highest level of all the countries covered here. Public funding accounted for 86% of ARD’s total revenues of €6,942m, and 85% of ZDF’s €2,254m, with the rest coming from commercial sources (EAO 2016; see table 2). Combined, the German public service media have the largest public service budgets in the world.

Italy – RAI

RAI is Italy’s national state-owned public service broadcaster. It is an integrated organisation for TV and radio. RAI is funded primarily by licence fee but relies on commercial sources for almost 40% of its total income, more than public service media in any other country covered apart from Poland. Political instability in Italy and frequent changes in government, combined with a governance structure that allows for more direct political influence than in some other countries, has led to a constant change in management in RAI, something that has previously been highlighted as holding back its development of digital content and services (Brevini 2013).

RAI channels have a strong overall position in Italian television, accounting for a combined total daily audience share of 38% in 2014 (EAO 2016). Television is also the most widely used source of news in Italy. While RAI’s news bulletins are popular on TV according to the Digital News Report 2015, RAI has only limited reach online. The RAI.TV website was named by 15% of respondents as a source of news (see Table 1). Online, the sites of national newspapers like Republica.it (29%) and digital-only offerings like Google News (22%) are far more widely used (Newman et al. 2015).

Almost a quarter of Italian respondents identify their smartphone as their main way of accessing news online. Social media are particularly important in Italy. 46% of respondents say they use social media specifically as a source of news weekly. Again, Facebook is the most widely used site for news, followed by YouTube (Newman et al. 2015).

Public service media funding in Italy was at €26 per capita in 2014. Of the countries covered here, only Poland has lower levels of funding. The funding comes from a licence fee which was €113.50 in 2015. Recently, the Italian government has reduced this to €100 while simultaneously cracking down on widespread evasion (estimated at 26% of all households): from July 2016 all the Italian electricity bills will have a surcharge for the RAI licence fee. Public funding accounted for just over 60% of RAI’s total of €2,595m revenues in 2014 (EAO 2016; see table 2), the rest came from commercial sources, most importantly television advertising.

Poland – Telewizja Polska and Polskie Radio

As in France, public service media in Poland are organised into separate organisations each built around a particular kind of traditional broadcasting: Telewizja Polska (TVP) and Polskie Radio. Both are state-owned. For public service media in Poland, commercial revenues are very important, and licence fee revenues relatively limited. As a consequence, some observers see Polish public service media as operating in ways very similar to their commercial, privately owned competitors. As noted in the introduction, the governance of public service media in Poland has changed significantly in 2016 with the introduction of a new media law that gives the government much more direct control. 7 This has been subject to critique from outside observers and has led the European commission to start a preliminary assessment of whether the new law represents a ‘systemic threat’ to fundamental EU values. 8 Of Telewizja Polska (TVP) revenues, 31% is from public funds with the rest from commercial sources, while 61% of Polskie Radio funding is from public sources, with the rest commercial (EAO 2016; see Table 2).

The UK – The BBC

The BBC is the world’s oldest national broadcasting organisation (founded 1922) and the largest broadcaster in the world by number of employees. It is an integrated organisation for TV and radio and serves the whole of the UK. Apart from its national services it also operates the BBC World Service and BBC Worldwide, its main commercial arm. The BBC’s domestic services are almost exclusively funded by licence fee. The BBC is established under a royal charter. The current charter came into effect in 2007 and is due to expire in 2016, with the charter process renewal currently under way.

In the UK in 2013, the BBC had a relatively strong position in television with a combined daily audience share for all channels of 35% (EAO 2014). The BBC has a particularly strong position in the UK when it comes to news. According to the Digital News Report 2015, it reaches 72% of respondents via traditional television and radio on a weekly basis. It has far wider reach than the second most widely source of offline news in the UK, ITV (used by 32%). The BBC is also strong in online news. Almost half of respondents (48%) report using BBC Online, making it not only the most popular source of online news in the UK, but also the most successful of all organisations in the 12 countries covered in the 2015 Digital News Report (see Table 1). After the BBC, the most widely used sources of online news in the UK are the Mail Online (14%), the Huffington Post (12%) and the Guardian online (12%) (Newman et al. 2015).

Of respondents in the UK, 27% mentioned smartphones as their main way of accessing online news. Half of smartphone users also said they use the BBC news app. Social media are used by 36% of respondents specifically as a source of news on a weekly basis. Facebook is the most important social network for coming into contact with news, followed by Twitter. YouTube, which is widely used in most other countries covered here, is only named by 7% in the UK as a place where they find news (Newman et al. 2015).

Public funding for public service media was €76 per capita in the UK in 2014. The annual licence fee is £145.50 per household. An estimated 82% of the BBC’s total revenues of €5,961m came from public funds in 2014 (EAO 2016; see table 2). 9

Public Service News Approaches to Organisational Change and Innovation

People in every public service organisation in all the countries covered highlight the importance of organisational change and innovation to delivering public service news more effectively online. But the different public service media organisations have very different approaches, both in terms of how news production is organised, and of how innovation processes are managed and supported.

Organising Public Service News Provision

Some organisations have integrated newsrooms working across all channels and platforms, others still have newsrooms organised around distinctions between offline platforms like radio and television and digital platforms including website, mobile apps, and social media channels. In Finland and the UK, public service newsrooms have been integrated for years.

Yle in Finland integrated its newsroom in 2007 and implemented further reforms a year and a half ago, when it was decided that every journalist should work for all media platforms (some are still designated as radio or television specialists). This more recent reform was widely discussed in the organisation before it was implemented, and explicitly framed as part of preparations for a digital future: ‘We felt like the internet is going to be everywhere and it is everybody’s job to be able to understand the digital logic and to do stuff for the digital platforms, whether it’s desktop or laptop or mobile phone or watch’, says Mika Rahkonen, Head of Development in Yle News and Current Affairs. 10

Journalists at Yle are now asked to think more about the angle and presentation of each story and only then to decide on the appropriate media or platform. Rahkonen explains:

If it’s a very visual story with lots of video, we can put it on TV, we can have a long video on the internet. And if it’s a story with lots of numbers, we can do a data visualisation and stuff like that. It used to be like slot first. Now it’s story first. 11

Atte Jääskeläinen, Director of News and Current Affairs, explains that the organisational structure of Yle News and Current Affairs is meant to ensure that there is one content manager who has the power to make decisions with respect to the type of media that should be privileged in cases where different media disagree over how to cover a story and how to publish it. Jääskeläinen says such conflicts were quite common initially, but have decreased over time as editors and journalists ‘have learned the basic rules’. 12

While Yle’s current news strategy prioritises online distribution first, and in general does not hold back news for traditional broadcasting bulletins, the interviewees were already talking about transitioning to mobile-first as the next logical step (more on this below).

The BBC introduced an integrated newsroom in 2008, moving from a separation between broadcast bulletins, the 24-hour news channel, BBC World, and online to one multimedia newsroom that emphasised an integrated leadership, co-location, and sharing of information. Today, journalists working there are trained to be multi-media providers, and content from various channels like BBC News Channel, Radio 4 and so on is used across the whole news division and repurposed for other platforms. Michael Hedley, Head of Strategy, News at the BBC, explains:

We really serve audiences with the most appropriate form of content for that period. So if a journalist is out in the field preparing a TV bulletin, they may be also at the same time writing a piece for online, or doing a short piece to camera, they may be doing a piece to radio, and then they’ll cut and do a piece to TV and so on. 13

In 2013, when BBC News moved into a new, specially designed newsroom in New Broadcasting House, the integration was taken a step further. Global and UK output was brought together, all intake processed through the same content management systems, and content for digital platforms was made first priority for all breaking news. As BBC Director of News James Harding put it then: ‘We are all digital journalists now.’ 14 And this is not only about a digital-first approach to news, but also about constantly evolving as digital media evolves. According to BBC Executive Editor, Digital, Steve Herrmann, the focus is increasingly on live, social, and mobile news. 15

In other public service media organisations elsewhere in Europe, the situation is quite different. In Germany, there is some cooperation and collaboration between the traditional media and online, though not to the same extent as in Finland or the UK. At ARD Aktuell, there is exchange on the planning level of television programme and online content. But apart from this, television and online journalists work in separate newsrooms since an earlier attempt to introduce an integrated newsroom was judged a failure. (According to one report, the TV journalists felt disturbed by their noisy online colleagues. 16

The traditional structure also leads to television and online working with different content management systems, which requires journalists to learn to work with both media. When it comes to radio, Krogmann says, cooperation is relatively strong. 17 However, these employees are not present in either television or online newsrooms. This is in part because Germany has no nationwide ARD-radio, instead, the nine regional PSBs all have their own radio channels.

At Germany’s other national public service media organisation, ZDF, the structure is also relatively traditional, with television and online journalists working in parallel with little integration. However, ZDF has launched a new venture called ‘heute express’ in 2015, a short news format for online programming (including social media) and TV. These short news programmes are produced by a cross-media team to avoid replication and save resources. Furthermore, ZDF has launched a late night news show heute+, a cross media format, in the same year, replacing the traditional former night edition of the heute news bulletin (see box below).

19 The newsroom is divided into three parts: Desk 1 produces breaking news and publishes them on a newsfeed updated from 6am to midnight called ‘live’. The staff working at Desk 1 tend to work only on text-formats and publish immediate news that they call ‘hot news’. Desk 2 works on images and video and often on news that requires one or two hours of work before publication. Finally, Desk 3 works on news that is published at the end of the day or the following one and aims to provide more background, depth, and perspective. Most of the journalists at FranceTV Info primarily work at their desk. Only the journalists working for Desk 3 occasionally go into the field to collect information.

News production at France Télévisions is thus still primarily organised around platforms, like at ARD and ZDF, but in contrast to the BBC and Yle. Plans for a more integrated newsroom are mentioned, however, in the context of a planned 24-hour news channel. The new channel is still not definite but is a plan that France Télévisions has had for years, adapted to take into account the rise of digital media. Cathala says:

We are in late and we try to make up for this delay: we already had this plan [for a 24-hour news channel] in the 2000s, but at the time the government prohibited it because they thought there was not room for several all-news channels in France. . . . But we are trying to transform this situation to an advantage because we want to imagine it digital first. 20

At RAI, the PSB in Italy, news production has long been highly decentralised. Each of the main RAI television channels (Raiuno, Raidue, Raitre, and Rainews24) has their own news division, whereas the RAI radio channels’ news bulletins have a centralised newsroom. This decentralised structure was replicated when RAI started offering online news, and every television and radio channel (even many individual programmes) opened their own news website and later social media pages. Only in 2013 was Rainews.it made into a common news website drawing on all parts of RAI, with the aim of aggregating content from across the organisation in one place and more effectively competing for audiences’ attention online.

However, our interviews suggest that some directors of news operations elsewhere in RAI accepted this decision only reluctantly. From their point of view, they were being asked to give up their own independent websites and contribute support to the joint website, thus draining their resources and undermining their independence. In practice, some management of decentralised newsrooms continue to resist providing the newsroom of Rainews.it with stories, even when they have already broadcast the stories on their own channel or show. Within the organisation, television is still seen as more important than online by many, not only management, but also by journalists who, when asked to work for multimedia projects, consider online journalists to have lower status and a more limited audience than television journalists.

Monica Maggioni, who was appointed President of RAI in August 2015, speaks frankly about some of the issues confronting RAI’s online news operation and what she plans to do to tackle them.

If we want to provide an honest description of the RAI situation, we have to describe also a delay, because this is the truth. RAI, but also some other European networks, is facing this delay because, for decades, we have been, by nature, focusing on linear television, and this has taken our best energies, creativity and production ability. When we realised the world was going in another direction, we started to do projects, but these initiatives weren’t necessarily well-coordinated, not necessarily going in the right direction, provided that a ‘right direction’ exists. The change phase started a couple of years ago, when we realised that the development of our 24-hour channel [Rainews24] was an essential passage to move also in the direction of the online news. 21

In December 2015, RAI established a new digital division. Monica Maggioni explains that the new division has been created to overcome the traditional separation between the editorial and the technological parts of the organisation, and will be able to ‘talk with all RAI sectors and to ask them for content’. She says it will provide ‘a connection point between the endless bunch of RAI contents and the final user’. 22 The Head of the New Division is currently working on restructuring the whole RAI digital offer. The aim for the future is RAI’s ‘transition from public service broadcaster – as we still are today – to public service media’, says Andrea Fabiano, Deputy-Director of Raiuno. 23

Finally, in Poland, public service media are (as in France) organised around legacy broadcast platforms with Telewizja Polska (TVP) built around television and Polskie Radio around radio. One interviewee describes Polish public service media as being at the ‘beginning of [a] road’ from being public service broadcasters to being public service media – and adds that the transition might take several years. (Internet use and smartphone penetration is also lower in Poland than most other countries covered here.) The situation is described as in some ways similar to that in Italy: every radio and television channel has its own newsroom. However, the news website TVP.info is described as a hub for online news from all television channels and polskieradio.pl for online news from all radio channels and programmes. In terms of news production, television and radio journalists typically do the actual reporting and produce stories for their respective broadcast platform, leaving it to editors back in the newsroom to adopt the content for online publication. At the beginning of 2016, however, TVP.info had started a new project with ‘mojos’ (mobile journalists) producing audio-visual content exclusively for the website.

Our interviews show a wide variety of different organisational structures and workflows across public service news provision in Europe. In some organisations like Yle and to some extent the BBC, news production is highly integrated and the approach is story-first, rather than format-first. But in most public service media organisations, news production is still structured primarily around legacy broadcast media and online news largely seen as separate, with various degrees of collaboration between broadcast journalists and online journalists when it comes to sharing of content and often limited investments made in digital-first news production (compared to the resources invested in broadcast news).

Innovation and Development

Similar differences are clear in terms of how public service media manage and invest in innovation in news. Some public service media organisations have teams dedicated specifically to developing new approaches and ideas for digital news. Others have a less formalised structure where innovation is based on individual staff members within the newsroom developing new ideas and building support for them. (All the organisations covered have their development and/or innovation teams elsewhere, but not all have such units in the newsroom or with a specific focus on news.)

Again, Yle in Finland and the BBC in the UK stand out for having invested significant resources in building teams tasked with innovation in news production and distribution.

At Yle the web and mobile development team consists of eight staff members who are supported by five to ten additional freelance subcontractors, depending on the situation, according to Aki Kekäläinen, Head of Web and Mobile Development at Yle. (The team also draws on the resources of the broader development department at Yle.) The decision to organise the development team as a separate department is meant to give them freedom from day-to-day work, so as to enable them to ‘[focus] on what should happen, what we should do so that we are on top of things in the future as well’. 24

In order to generate ideas on a continuous basis, the Yle web and mobile development office has a regular meeting every Tuesday from 10am to 3pm to brainstorm new ideas to respond to the changing media environment. The team of approximately ten people (some on staff, others on subcontracts) is divided into groups of three or four. Aki Kekäläinen describes the meetings:

We focus on a topic. . . . We crunch the numbers and we check the statistics and in some cases we do benchmarking. . . . What’s the best already available, the baseline that we should do at least as well as they’re doing, and why are they the best example? Or do we need to do some user research? We could go and interview some people or at least think though how we might research the question. Or we can build [a] prototype and try it out. 25

Kekäläinen points out that the work organisation in small groups is an important factor in this context, leading to fruitful discussions where the teams challenge each other and thus further develop ideas.

Similarly, BBC News has had a ‘BBC News Lab’ to support innovation in news since 2012 (see box below).

In Germany, ARD has a small team of four people working with strategy and innovation development specifically for news, Kai Gniffke, First Editor in Chief of ARD Aktuell, explains. 27 Similarly, at Polskie Radio, a group of about five staff members are tasked, among other things, with observing new developments, going on field trips, and exchanging information and know-how with EBU partners. France Télévisions did not have a development team specifically for news when we did our interviews, but was just about to start one.

At ZDF, there is a development team for new media in general, but not one specifically focused on news. Instead, small decentralised groups work on innovations for news. 28 Elmar Theveßen, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Head of News, ZDF, describes the ZDF newsroom’s approach to innovation as ‘learning by doing’ on the basis of information they gather, for example through the EBU, field trips to innovative newsrooms, and conversations with commercial broadcasters. 29 The approach at the Italian RAI and Polish PSB is similar. Currently there are no teams in place for regular development specifically focused on news. RAI maintains a small, so-called WebLab in the online newsroom. This group, however, focuses mostly on storytelling in the digital age and less on broader strategic issues, explains Roberto Mastroianni, News Editor and Media Manager at Rainews24. 30

European public service media thus do not only differ in terms of how they organise online news provision, but also in terms of how they have organised innovation around online news. Some have teams or units in place specifically tasked with thinking about ways in which the wider organisation could or should change. In most cases, however, innovation is based on a combination of ad-hoc teams put together from people who have other day-to-day responsibilities in the newsroom and development departments elsewhere in the organisation.

Public Service News Approaches to Mobile News

The rapid move from a desktop web to a mobile web in recent years is one of the central developments in digital media. Desktop use has been broadly stable, while mobile use has grown explosively in just a few years, and already accounts for over half of time spent with digital media in some countries and more than half of all traffic for many news sites. The pace of change differs from country to country, but increasingly, the smartphone looks like the defining device for digital news (Newman et al. 2015). Most of the public service media organisations we cover in this report are aware of this development, but the degree and ways in which they have adapted their digital news provision for mobile differ.

The BBC launched its mobile news app in 2010 to supplement the website the corporation has run since 1997. Both the website and the news app were redesigned in 2015. The website switched to responsive design to ensure it worked across personal computers, tablets, and smartphones, with a cleaner design, faster load times, and a greater emphasis on video. Similarly, the news app was relaunched to include a broader range of content, to integrate more video, and offer more ways for people to discover content by supplementing the edited front page with ‘most read’ and ‘most viewed’ sections and the ability to follow topics and stories with a personalisable ‘My News’ section. 31 Michael Hedley, Head of Strategy, News, at BBC, describes the app mainly as ‘an interface to get into BBC news content’, with a strong possibility ‘to personalise the news’. This is possible by streams, but also by topics and by location. ‘It’s a faster, more accessible experience’, Hedley says. 32

One of the features of the app that BBC News is constantly trying to get right is the balance between general news selected for people on the basis of their expressed preferences and past use. Daniel Wilson, Head of UK Policy at the BBC, underlines that while the new app enables personalisation, it also ensures that all users get the most important news, as well as articles that may be neither general news nor personalised news, but might still surprise and interest people – what he calls ‘serendipitous’ content.

The idea is that through much more use of data and with [the] audience’s consent, we will be able to optimise much better the journeys between the things that people already know they like, and the things that they don’t know they like, and the things that they don’t know are important. If we can keep bringing together the important, the popular and the serendipitous, then I think we’re doing a good job. 33

Looking forward, the BBC has indicated its plans to make ‘a transition from rolling news to streaming news’ with the announcement of a project called ‘BBC Newstream’. 34

Although Yle sees its new app as successful, it is still only ‘serving a niche’, according to Tuija Aalto (Yle). Atte Jääskeläinen makes the same point:

NewsWatch is a kind of platinum product for heavy news users. . . . The features are very kind of high end, what they have in NewsWatch and for regular news customers they may be a little bit too much if you choose from 140,000 keywords. 36

Yle is now redesigning its responsive news website that was among the first of its kind worldwide when launched in 2012. It is planning to bring the personalisation of the app to the news website itself. In order to prepare journalists for a mobile-first strategy, Mika Rahkonen says that Yle is planning to have big screens in the newsroom showing exactly what is seen on a mobile screen. 37

For ARD in Germany, their mobile strategy is deeply intertwined with the wider political discussion of the role and remit of public service media online, specifically the ongoing court case brought by several newspapers against the ARD after the Tagesschau news app launched in 2010. The newspapers are arguing that the app is too similar to their offerings, distorts the market, and does not represent the kind of ‘programme-related content’ German public service media are restricted to offering online. It seems clear that the ongoing court case has limited investment in developing the app. However, the ARD are aware of issues around navigation, the presentation of videos, and load times that they would like to address. Kai Gniffke (ARD) describes the main focus of the app as providing an overview of all relevant news of the day, partly enriched with background information and analysis. 38 His colleague Christiane Krogmann (ARD) explains that due to the German requirement that public service offerings online must be programme-related, the ARD cannot offer the app as a stand-alone news product and the content it presents has to be related to existing ARD broadcast output. 39

Germany’s ZDF also plans to relaunch both their news website and the news app they have built around their main evening news bulletin heute. The relaunch is scheduled to happen no later than 2018. Amongst the priorities for the relaunch of the website and app, Elmar Theveßen (ZDF) mentions personalisation of content as well a stronger focus on video. 40

In France, the main news website, FranceTV Info of France Télévisions, has had a responsive design since 2011. In addition, France Télévisions introduced a news app the same year. Like the other news apps discussed above, the FranceTV Info app includes an overview of news with background articles, video streams, and notifications for important stories. In addition, a unique feature of the app is an information feed called ‘live’. Jean-François Fogel, who works as a consultant for France Télévisions, explains:

The most innovative aspect of FranceTV Info is ‘live’ . . . The ‘live’ stream is a way to produce information and to have a permanent conversation with our audience (they ask questions on the live, and our journalists provide answers). . . . It is important to mention also the fact that we publish on our live both the contents we produce and those produced by other news outlets, including those produced by private media. 41

Rainews, the structure in charge of the RAI digital news offer, has likewise developed a news app offering news both on text and video formats. The app also provides on-demand videos, live streaming and push notifications. However, several interviewees say that, so far, RAI’s top management have not considered mobile strategies as being as important as traditional media activities. This is in line with previous research which has suggested that RAI has historically not been a particularly innovative public service provider, which in turn has impacted its reach online (Brevini 2013). The RAI President Monica Maggioni underlines that the new digital division is currently working on product personalisation and platform designing to make RAI news to become ‘more attractive . . . within the social media and mobile channels’. 42

Poland is the country covered here with the lowest smartphone penetration and the lowest number of people naming mobile devices as their main way of accessing online news. It is also the only country where the public service media do not offer dedicated news apps, but just general apps. However, both their news websites are built with responsive design to facilitate mobile use. One interviewee mentions that Polskie Radio is currently planning a news app which will rely mainly on audio with very little text and pictures. This means that it is likely to be more of an audio than a multimedia app.

As with the organisation of newsroom work and innovation, there are clear differences in terms of how public service media organisations across the countries covered approach mobile news. The BBC and Yle have dedicated mobile news apps that offer general news and personalised content in both text, audio and video formats, and have websites built with responsive design facilitating both desktop and mobile access. The Yle is developing a mobile-first strategy. France Télévisions is moving in the same direction with a dedicated mobile news app and a responsive design website, and is working on personalisation as well. In Germany, both ARD and ZDF have mobile news apps, but they are tied to specific broadcast news programmes and development of mobile offerings is slowed by legal challenges and political pressures. After the gradual centralisation of RAI’s online news offerings, Rainews has also developed and launched a mobile app, but our interviews suggest the development is hampered by internal indifference and resistance from some parts of the organisation. In Poland, TVP and PR have responsive design websites and general apps, but no news app for mobile as yet.

Public Service News Approaches to Social Media Distribution

As with organisational change and mobile strategy, public service media across Europe differ in terms of how they approach social media distribution and think about their relations with increasingly important digital intermediaries such as search engines, video-hosting sites, messaging apps, and – when it comes to news perhaps most importantly – social media sites.

Daniel Wilson from the BBC offers two different perspectives on this topic:

The whole industry is struggling between trying to keep their website, their app, their environment as the point of contact for their audiences and maintaining that control versus the challenge of audiences increasingly going to other big international platforms like Facebook, Google, and other social media such as Twitter. I think there are two extremes. You can either say you want to be a platform in your own right, and you don’t want to link out to anyone else or disaggregate your content in any way, or you can say it’s all publicly funded content, everyone should have access to it everywhere. 43

Most of the public service media organisations covered here try to position themselves between these extremes and combine an emphasis on their own destination websites and mobile apps along with attempts to leverage social media distribution in particular to maximise public service reach.

In no other area is the language of opportunities and risks more appropriate or more frequently invoked than when it comes to the relationship between public service media and third-party platforms like social media.

Challenges and Opportunities Associated with Social Media Distribution

Our interviewees highlight in particular two reasons for investing in social media distribution. One is referrals, the other is off-site distribution.

To Bring Users to their Own Website and Not Lose Traffic

Interviewees in all six countries point out that social media are important drivers of traffic to their websites. Data from comScore support this (see Table 3 on the next page). With some variation, all the organisations covered here get a substantial share of their traffic from Google and Facebook (and a fraction from Twitter). Thus, some interviewees argue that not being active and present on social media platforms would lead to a loss of audience. Atte Jääskeläinen from Yle argues that, especially for mobile users, ‘they are not visiting that many different pages or opening that many different applications. So we would lose a big part of our audience if there wasn’t social media or we weren’t on social media.’ 44

Internal audience research from one organisation suggests there is good evidence to support this point of view – while the vast majority of users who go direct to that particular organisation’s website and app are returning users, social media referrals account for most new users drawn in, and thus represent a major opportunity to reach beyond an existing loyal audience.

To Reach Young Audience and Light News Users Off-Site

To Reach Young Audience and Light News Users Off-Site

Several interviewees see social media, especially Facebook, as a way of reaching younger users as well as light users who otherwise would not necessarily come to the PSB websites. This is in part about drawing people who do not seek out news of their own volition to public service news sites and news apps through referrals, but also about placing public service news on off-site platforms where people who will not click on the link may still enjoy the content. Instead of only trying to draw people to public service news sites, it is about going to where they already are. Robert Amlung (ZDF) says that the main advantage from the users’ point of view is that social media have a whole range of different attractions well beyond news and in addition can aggregate content from many different players. For some users, this will make them more attractive sources of news than public service apps and sites that only contain content from one source, 45 and for some, they stumble upon news, including public service news, while they are on these sites for other purposes (Newman et al. 2015).

Despite the attractive opportunities for increased reach through referrals and off-site use, our interviewees also identify a range of risks they associate with third-party platforms and social media distribution in particular.

The Challenge of Building Relationships With Platforms

The key concern expressed by several interviewees is that social media platforms are not transparent and predictable in terms of their strategies and that public service media have little influence on them. Aki Kekäläinen from Yle illustrates this worry:

If money is the main driver, then commercially driven content could be more interesting for Facebook and if that happens then they just tweak their algorithm a little bit and our audience coming from Facebook drops significantly overnight. So if we don’t have any control it’s really bad for us. 46

The relationship between public service media and social media is discussed in several interviews, along with strategies to cope with the new dynamics. Tin Radovani, Strategy Analyst for the World Service at the BBC, says:

That sort of relationship is quite difficult to establish, and it’s quite difficult to bring value back to us since you are living in somebody else’s garden, in somebody’s else’s platform. So, it’s a developing relationship, and we are developing our understanding of how best to work in somebody else’s platform. 47

The Challenge to Fulfil the PSB Remit in a Disaggregated Environment

Several interviewees, especially from the BBC, also see potential risks in the tension between the public service obligation to provide information across the full range of relevant issues and the ways in which social media operate in practice. Daniel Wilson argues that this public service remit of the BBC could be harder to fulfil as content becomes more disaggregated – pointing to fears over potential ‘filter bubbles’ or ‘echo chambers’: ‘Disaggregating all your content effectively stops the BBC playing that public service role I mentioned earlier, linking the popular to the good, the popular to the important and providing variety in what audiences consume from the BBC.’ 48

The Challenge of Keeping Users’ Aware of Public Service Brands

A further challenge is how to ensure that users who encounter public service content on social media platforms recognise the brand and credit the public service media organisation for the content they use. Eric Scherer (France Télévisions) says:

With these platforms, there is the risk of losing control over your distribution process and, possibly, over the relationship we have with our audience. At the same time, if we don’t go there, we risk losing a large part of the audience: young people who don’t watch TV. 49

Andrzej Mietkowski, Responsible for New Media at Polskie Radio, express a similar view:

You have to work on your own image, to build your own credibility and to make a distinction for the users that you are the Polish Radio, you are not Mr John Smith. And when you start to use the social media, which is the environment of John Smith, you have to make it with a lot of precautions, and to have in mind that you cannot play on the same level, the same rules, the same games for people. 50

Beyond the opportunities and challenges social media and the like present for public service media, one interviewee expressed a more fundamental worry about national commercial media ultimately being subsumed by the ascendance of social media platforms, leading to a less diverse media environment:

I fear that the commercial publishers will jump into that, and in that sense, we’ll lose the kind of last hope of surviving in this environment if they jump into social media giants’ boat in which they don’t really have a voice and control over the future. So I think that there will be a major change in the environment in that sense. 51

Most public service organisations thus see considerable opportunities in social media distribution, especially around referrals and off-site use. It is clear that all of them get significant proportions of their website traffic specifically from search engines and social media. Some of them also have considerable off-site reach via a range of social media platforms. The analytics company Tubular Labs estimates that BBC News had a social reach of more than 87 million impressions globally across YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and Vine in January 2016, not far behind its estimated c.100 million global monthly unique website users. 52 But there are also challenges around the risk of relying on third-party platforms for distribution, editorial control in distributed environments, and fears that users will not necessarily appreciate content producers when they encounter their news via third-party platforms.

Social Media Strategies

Despite the reservations they have, public service media are actively developing strategies for making the most of the opportunities offered by social media.

In Finland, Facebook is described as the most important social media platform for Yle news. However, they use a variety of platforms and Mika Rahkonen (Yle) points out that flexibility and adaptation to new situations is required:

The important thing in terms of the development department is to think big. We’re here to re-invent news. And to re-invent the ways to consume news, to keep up to date and be informed and entertained and so on. It means many things, and some of those we don’t even understand yet. What we do understand is that we have to be so flexible that we can do stuff like in one month. Okay, here’s a new platform, it looks really great, it seems that the kids are there, what are we doing there, what are we doing there that we look cool there, that we don’t look stupid, that we don’t look like your grandpa is trying to learn new platforms because that’s immensely important. 53

Distributing news not only via public service media’s own websites and apps but also via social media requires changes in how the news is produced. Panu Pokkinen, Head of Sports at Yle, argues that as the front page is becoming less important because more and more people arrive at individual articles via social media, ‘we have to put our effort into how to structure one article and to try to persuade people to find another article or a third article to read with that’. 54

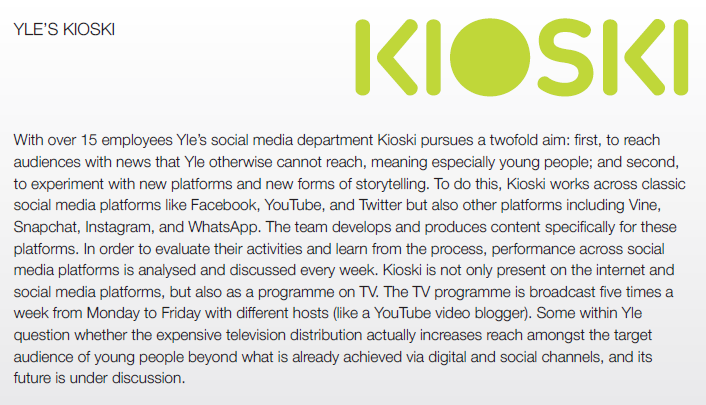

About a year ago, Yle started a department called Kioski in order to deal with social media distribution (see the box below).

In the UK, the BBC has also established a social news team to make the best use of social networks for distributing news and engaging with the audience. BBC News has long worked with social media both as a means of news reporting and news distribution (Belair-Gagnon 2015) and many channels and news programmes have built their own social media profiles. Throughout 2015, BBC News continued to reorganise its social media presence, rationalising its Facebook presence with the creation of a single shared page while continuing to experiment with and use newer tools like Periscope, Telegram, and YikYak. 55 Examples of social media initiatives are BBC Shorts,15-second videos primarily produced for Instagram in a way that users can understand the story with the sound off, BBC Trending, a service reporting on trending topics on the internet, and Go Figure, an image format delivering key statistics optimised for social channels.

In the UK, the BBC has also established a social news team to make the best use of social networks for distributing news and engaging with the audience. BBC News has long worked with social media both as a means of news reporting and news distribution (Belair-Gagnon 2015) and many channels and news programmes have built their own social media profiles. Throughout 2015, BBC News continued to reorganise its social media presence, rationalising its Facebook presence with the creation of a single shared page while continuing to experiment with and use newer tools like Periscope, Telegram, and YikYak. 55 Examples of social media initiatives are BBC Shorts,15-second videos primarily produced for Instagram in a way that users can understand the story with the sound off, BBC Trending, a service reporting on trending topics on the internet, and Go Figure, an image format delivering key statistics optimised for social channels.

In Germany, ARD is also experimenting with different social media platforms to distribute news content. They concentrate on Facebook and Twitter, with Twitter described more as a platform to reach other journalists, public figures, and communicators in society and less to reach a wider audience. Tagesschau.de has also agreed to participate in Instant Articles on Facebook. In-house, especially concerning the Instant Article cooperation with Facebook, people talk about a ‘marriage of convenience and not out of love’, says Christiane Krogmann (ARD). 56 ‘Sweet poison’ is Kai Gniffke’s (ARD) metaphor for the relationship. 57 Despite such reservations, ARD has decided to pursue this step to reach users who do not come to the PSB‘s own news website. Christiane Krogmann (ARD) says that the decision marks the beginning of a trial period which will be followed by an evaluation. 58

In addition, tagesschau.de has just established a new video team to produce content exclusively for Instagram, since they see this platform as growing in popularity, and also to conduct some testing of WhatsApp with a sample group of young users. At present, according to Christiane Krogmann (ARD), the main aim is to find forms of presentation that fit each platform best:

This means, if we put our videos on Facebook, we try to find an optimal presentation for this platform. We try to work with different means. For example, we only put cuttings of interviews or a core sentence on a photograph. We also often try to have subtitles. . . . If you are sitting in a train and have no ear phones, it is a way to help and explain what you see on the screen. 59

In this way, tagesschau.de uses Facebook videos to deliver explanations for current situations, which has thus far worked well, since ‘the analysis provides a personal attitude and not just the pure news and this is most appreciated by the users’, says Krogmann (ARD). 60

In terms of social media, Germany‘s ZDF distributes news mainly via Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, but is also experimenting with Instagram and closely observing possibilities with Snapchat and WhatsApp. The ZDF interviewees highlight that different social media channels require different ways of presenting the news. Robert Amlung (ZDF) explains that, from his point of view, YouTube is closest to a traditional TV broadcaster. ZDF was also a launch partner for YouTube in Germany.

You can use the whole variety of TV formats also on YouTube and it works. You can do long formats, you can do short formats, you can do playlists, a programme sequence. . . . It is closer to where we come from. 61

Despite these advantages, he also points out that YouTube brings other challenges for a traditional TV broadcaster like questions of copyright or the challenge to draw the attention of users to the YouTube channel. Facebook, in contrast, he describes as more interactive and in general, with exceptions, more suitable for pictures and shorter videos of about a minute. The strategy for Twitter is not focused on videos, but just on pictures and text. With respect to Instagram, the organisation is in the preliminary phase of exploring what works well and what does not.

A focus of ZDF‘s social media activities is the interactive news show heute+, mentioned above, that is distributed via social media as well as ZDF-platforms and on traditional TV. Reaching a young target audience is the main aim behind these activities, as Elmar Theveßen (ZDF) points out: ‘We know that 80% of our users on Facebook [speaking about the heute+ account] are between 17 and 45 years old. This means, this is a target group that we do not reach with traditional TV news anymore.’ 62

In fact, Theveßen explains, ZDF’s main television news bulletin heute reaches only 170.000 viewers under 40, out of a total of 3.7 million viewers. ZDF is aware that a Facebook presence will not necessarily bring those users to the traditional TV programme, but it still provides a point of contact with younger people. 63

In France, public service media are also engaged in distributing news on social media platforms. However, France Télévisions does not yet have a designated team in charge of this expansion process. Facebook and Twitter are mentioned by the interviewees as the most important social media platforms for news distribution, ‘because Facebook is the platform with the largest part of the audience now, and Twitter is the place where you can influence the web dynamics’ says Jean-François Fogel, consultant at France Télévisions. 64 Furthermore, YouTube is used as a distribution platform, with France Télévisions having been the first French broadcaster to use it, as Eric Scherer, Director of Future Media at France Télévisions, notes. 65 Snapchat is seen as an interesting innovative platform, but also a challenge to a traditional broadcaster: ‘It is a problem for us, because they have walled gardens: you have to make products for discovering content there’ says Jean-François Fogel. 66

One interviewee says that France Télévisions’ approach to news distribution via social networks is somewhat hesitant, especially when it comes to the question of Instant Articles:

We refused to go on Facebook Instant Articles. This was our choice. Facebook is looking for content and we could provide content, but this must create value also for us, not only for Facebook. Therefore, for now, we said no. . . . I think we are not too interested in having tight collaborations with Facebook and Google. However, it is necessary to be present on these platforms. 67

At the moment, France Télévisions is just beginning to test new forms of storytelling for mobile screens and social media platforms, explains Jérôme Cathala (France Télévisions). 68 Laurent Guimier, Director of France Info, the all-news channel from Radio France, sees a ‘huge opportunity’ in social media distribution, but also a challenge of adapting the content for this purpose and in moderating interaction:

The only challenging aspect is that we have to invest in human resources that produces non-linear videos for Facebook. Another risk concerns the moderation of conversations linked to the content we distribute on these platforms. 69

At the Italian RAI, social media strategies reflect the more decentralised structure already discussed above. Some interviewees mention that certain news outlets are on social media platforms while others are not and that there is no corporate policy prescribing rules for social media use. One interviewee describes the situation like this:

RAI has a strong presence on social media. I personally think that we are too present on these platforms and that we repeated on these new platforms the bad habits that affected our first phase with news websites: many offers, mainly irrelevant. . . . Each of them with few people working on posting content. 70

Facebook and Twitter are described as the relevant social media platforms for news distribution. YouTube was relevant in the past, but there is no current agreement between RAI and YouTube. At stake in the discussion are the terms and conditions offered by YouTube and RAI’s concerns over its visibility, revenues, and ability to deliver public service via this platform.

More broadly, one interviewee argues, there is no general consensus in RAI on social media distribution. Rather, opinions diverge in two ideological directions:

On the one side, someone thinks that taking our content to other platforms is convenient only for the players that own these platforms. On the other side, people think that we have to go where the public is located; it is complicated to reach people if you don’t go in the environments where they are, and this is true especially if your products (your contents and the user experience you offer) are not particularly brilliant and innovative. According to the latter position, to reach the audience with our offer is a value in itself, beyond any implication in terms of revenues or commercial agreements. . . . I think that this conflict concerns in particular YouTube, Google News, Yahoo, and other similar platforms. Concerning social networks such as Facebook there are more open positions. 71

In this context, interviewees said they assumed the new management of RAI would pursue greater social media distribution. In fact, Monica Maggioni, the RAI President, points this way and says that RAI will focus more on social media distribution in order to reach young target groups:

We realised that our public is not where we are used to looking for it anymore; . . . Instead, we have to look for these people where they already are. And they are in the social media world, they live with their smartphones and tablets, and so we need to move our content offer to other platforms in order to become more interesting for them. 72

In Poland’s two public service media organisations, social media distribution is widely discussed. Twitter is mostly used in the context of news, while Facebook is seen as the most important social media platform for the distribution of entertainment content. Polskie Radio also mentions the use of YouTube. Andrzej Godlewski, Deputy Director of TVP1, mentions that during a televised debate between candidates before the last national election, the hashtag #TVP was the most popular in Poland. Andrzej Mietkowski, Polskie Radio, explains that besides the general Polskie Radio account there is also a news account, a business account, and a sports account. 73 However, the interviews suggest that there is no general strategy for social media distribution at Polish PSB and, likewise, no specialised teams. Other formats like adapted videos for social media are not produced: ‘We use social networks to deliver videos too, but as you see, if you click, you are directed to the TVP.info.’ 74

In sum, this chapter has shown that all countries in the sample use social media distribution for news, but to a varying degree. All are searching for the right combination of channels over which they have a higher degree of control, like their own websites and apps, and third-party platforms that offer greater reach and opportunities to reach especially younger audience if used well, but offer less control. Some organisations, like Yle and the BBC have developed social media teams as well as new editorial products that are specifically designed for social media distribution, like Kioski or BBC Trending. Other organisations have a more ad-hoc approach to social media and have so far invested less in developing public service news for social media distribution.

Conclusion

In this report, we have reviewed public service media organisations’ performance across six European countries in terms of their offline and online news provision and have analysed how they are working to 1) change their organisation, 2) develop mobile offerings, and 3) use social media to more effectively deliver public service news in an increasingly digital media environment.

Our interviews suggest that the BBC in the UK and Yle in Finland have consistently done more to change their organisation, invest in mobile offerings, and develop social media strategies than most other public service media organisations. Our review of public service media organisations’ performance also suggests that the BBC and Yle stand out in having built significantly broader reach online to match their offline reach, whereas many other public service media organisations, despite their offline strength, have only limited reach online.

What do these two high-performing organisations have in common? We would point to four external conditions over which public service media organisations themselves have little influence, but also two important internal factors that reflect public service media organisations themselves more than their environment.

External factors first. First of all, both the BBC and Yle operate in technologically advanced media markets, more so than many other public service broadcasters operating in countries with somewhat lower levels of internet use and smartphone penetration. Second, both are well-funded compared to many other public service media organisations. (Though Yle is in absolute terms a smaller organisation than most other public service media covered here.) Third, both are integrated and centrally organised public service media organisations working across all platforms and covering their entire country. Fourth, both have a degree of insulation from direct political influence by virtue of regulatory frameworks that place them one step removed from day-to-day governmental and parliamentary politics and create some certainty through multi-year agreements on public service remit, funding, etc. 75

These four external conditions are not in place in many of the other countries covered here. In Italy and Poland, for example, public service media organisations operate in less technologically advanced markets, have lower levels of per capita funding, are separated into multiple organisations and often run in a very decentralised fashion, and have less insulation from political influence. In Germany, public service media operate in a technologically advanced market and enjoy some of the highest funding levels in the world, but are organised in a decentralised fashion and face political pressures and legal constraints around their online offerings. In France, public service media are less well funded than in Finland and the UK and delivered by different organisations which are less insulated from political influence. These external factors are likely to hamper their ability to fully seize the opportunities presented by digital media.