Introduction

The new millennium has seen the rise and rapid global spread of what can fairly be called a new democratic institution, the independent political fact-checker. The first organisations dedicated to publicly evaluating the truth of political claims appeared in the United States in the early 2000s, anchoring what would become a staple of political reporting practised by nearly every major US news outlet. 1 Over the past decade, meanwhile, independent fact-checkers have emerged in more than 50 countries spanning every continent. According to the most reliable global count, 113 such groups are active today. More than 90% were established since 2010; about 50 launched in the past two years alone. 2

This report surveys the landscape of fact-checking outlets in Europe, a landscape which is remarkably diverse and fast-changing. The first regular source of political fact-checking appears to have been a blog launched by the United Kingdom’s Channel 4 News in 2005, to cover a parliamentary election. In 2008 similar efforts appeared in France and the Netherlands, and by the end of 2010 fact-checkers were active in ten countries. In all, more than 50 dedicated fact-checking outlets have launched across Europe over the past decade, though roughly a third of those have closed their doors or operate only occasionally.

Many European fact-checking outlets are attached to established news organisations, like Channel 4 News. But a majority – more than 60% in the companion survey conducted for this report – are not, operating either as independent ventures or as projects of a civil society organisation. Some reject the label of journalism altogether, and see fact-checking as a vehicle for political and media reform. This diversity matches the global picture. Current data from the Duke Reporters’ Lab, which maintains a database of fact-checking organisations around the world, suggests that just 63% of active outlets are affiliated with a media organisation. Discounting the United States, where newspapers have led the fact-checking push, the figure drops to 44%.

Different fact-checking outlets all share the laudable goal of promoting truth in public discourse. But political fact-checking always attracts controversy. Even simple factual questions can leave surprising room for disagreement, and fact-checkers often come under attack from critics who disagree with their verdicts. As a democratic institution the practice raises basic questions about what counts as reliable data, who has the authority to assess public truth, and how to balance accuracy with other democratic ideals such as openness and pluralism. It represents a clear challenge to legacy news outlets in Europe, whom fact-checkers depend on to publicise their work but in many cases see as an institution in dire need of change. Digital media help fact-checking outlets publish and promote their work online, but for wider reach, they still rely heavily on legacy media and work systematically to build relationships with them.

Finally, this new phenomenon invariably raises the question of what we can reasonably hope to accomplish by holding public figures accountable for false statements. In the US, political fact-checking was inescapable during the 2016 presidential race. Nevertheless, by many accounts public debate seemed unmoored from even basic facts; Donald Trump’s campaign in particular distorted the truth relentlessly and outrageously. Among media and political elites events like the US election and the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom have spurred anxious talk of a ‘post-fact’ or ‘post-truth’ age. 3 At the same time, a growing body of evidence suggests that, while it falls short of the sometimes utopian hopes attached to it, fact-checking can help to both dispel misinformation and inhibit political lying. 4

Data and Organisation

The report is divided into five sections. The first offers a broad overview of the kinds of organisations involved in fact-checking across Europe. The next two sections ask what fact-checkers hope to accomplish with their work and how they go about it, exploring variations in the mission and identity of these groups as well as in their day-to-day methods. The fourth section turns to the question of impacts – the results these efforts yield and the strategies fact-checkers use to magnify them, especially in managing their often fraught relationship with the news media. Finally, the report addresses the costs of fact-checking and the approaches these organisations have taken to make their work financially sustainable.

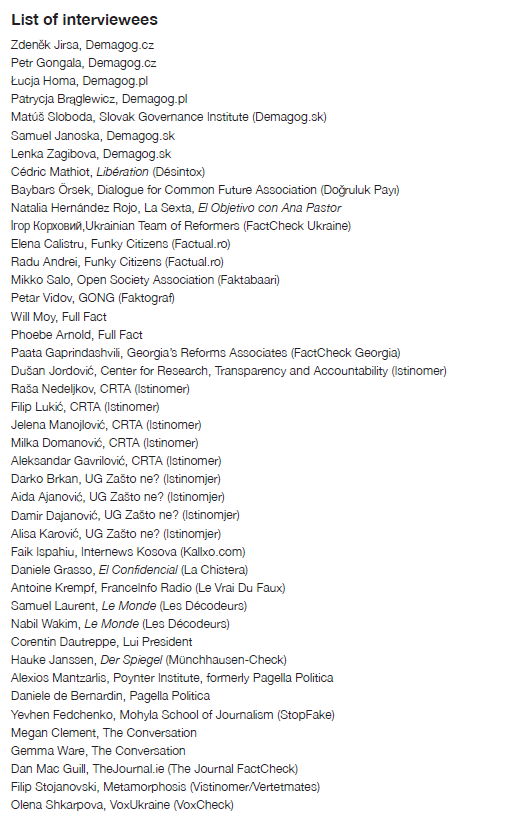

The analysis presented here draws on individual or group interviews with more than 40 practitioners, site visits to fact-checkers in eight different European countries, and an online survey of 30 organisations across the continent carried out in August and September of 2016. The bulk of the interviews and site visits took place in the summer of 2016, though a handful were conducted over the previous two years. In addition, the report is informed by observation of three global fact-checking summits, in London in 2014 and 2015 and Buenos Aires in 2016. The survey carried out for this report is supplemented with data from a May 2016 online survey by the Poynter Institute, and with September 2016 data from the Duke Reporters’ Lab database.

Overview

Today at least 34 permanent sources of political fact-checking are active in 20 different European countries, from Ireland to Turkey. They can be found on every part of the continent, including the Nordic countries, the Mediterranean, Central Europe, the Balkans, and the former Soviet republics. In addition, fact-checking as a genre is sufficiently well established that many news outlets without dedicated teams offer it on an ad hoc basis, for instance during major political campaigns. In the weeks before the Brexit vote in June 2016, misleading claims from both camps were being debunked across the British media, by leading national outlets but also many local newspapers and TV stations.

This landscape defies easy categorisation. Almost all of the outlets featured in this report focus on investigating claims by political figures, but several also target the news media. The fact-checkers themselves come from a range of backgrounds, including journalism but also political science, economics, law, public policy, and various forms of activism.

As developed in the next section, in terms of their mission and their methods, fact-checking outlets occupy a spectrum between reporters, concerned mainly with providing information to citizens, and reformers, focused on promoting institutional development or change in politics and/or the news media. A third, overlapping category includes organisations which have cultivated a role as independent experts, along the lines of a think tank. At the outset, however, it is important to differentiate outlets based in a larger newsroom from those that are not, a distinction that lines up roughly with regional variations. In general, political fact-checking in the North and West of Europe has been led by legacy newsrooms, joined by a handful of independent outlets. In the East and the South, meanwhile, the practice is less a supplement to conventional journalism than an alternative to it, based almost entirely in NGOs and alternative media outlets.

The Newsroom Model

While a minority of permanent fact-checkers in Europe are affiliated with an established media company, the legacy news media remain the dominant source of political fact-checking. This is especially true in Western Europe, where national newspapers and broadcasters have incubated the trend and provide its most visible examples. Fact-checkers based in traditional newsrooms have a tremendous natural advantage in terms of reach and resources, as discussed below. But they remain dependent on the editorial interest and financial support of their media parent, and many have lapsed when that support waned.

France offers a striking illustration of widespread fact-checking by legacy news outlets. The first and still most prominent French fact-checkers are Libération’s Désintox, launched in 2008, and Le Monde’s Les Décodeurs, which followed in 2009. The next three years saw the launch of Les Pinocchios, from Le Nouvel Observateur, Le Véritometre, carried by the TV network i>Télé, and Le Vrai du Faux, from the radio and TV network FranceInfo. The first two of the latter three are now defunct, but other news organisations with active fact-checking outlets today include the radio network Europe1, the private news service Facta Media, and Les Observateurs, an online hub and TV programme from the multilingual network France24. Meanwhile, ad hoc or one-off fact-checks are increasingly normal in French journalism. In a recent France 3 documentary, former prime minister Alain Juppé complained of the ‘mania’ for fact-checking that has overtaken the country’s media (Juppé 2016).

A similar trend can be seen in the UK. Channel 4 News revived its FactCheck as a permanent feature in 2010, and the Guardian has run its Reality Check blog more or less regularly since 2011. The BBC has also experimented with the format, and introduced a dedicated Reality Check team in 2015 to cover the Brexit referendum. (Meanwhile, ITV, the Telegraph, and other outlets have partnered with the independent site Full Fact.) In Germany, Der Spiegel introduced its Münchhausen-Check in 2012; Die Zeit followed with Faktomat, and ZDF television with ZDFcheck. None of the three is active today, but episodic fact-checking remains widely available. ‘It’s really a little bit of hype here,’ said Dr Hauke Janssen, research director for Der Spiegel. ‘Everybody now does fact-checking.’ Sweden’s Metro features regular fact-checking, as does the Dutch member-funded news platform Der Correspondent. Denmark’s public broadcaster offers a fact-checking show called Detektor, which debuted in 2011 on both TV and radio.

Fact-checking teams attached to media companies can assemble audiences which vastly exceed the reach of most independent fact-checkers. This is particularly true for the handful attached to successful broadcasters. The fact-checking segments on El Objetivo con Ana Pastor, a highly rated weekly public affairs programme on the Spanish TV network La Sexta, go out to between 1.5 and 2 million viewers each Sunday – perhaps the largest regular audience for a dedicated fact-checking operation in Europe. Virus, a weekly current affairs programme which ran on Italy’s RAI for three seasons and featured fact-checking by the site Pagella Politica, had an average audience of 1 million viewers. While Channel 4 News concentrates its fact-checking work online, some items air as video packages to the nightly news audience of more than 650,000 viewers. Fact-checkers for the BBC’s Reality Check have appeared on high-reach outlets including the BBC News Channel, BBC World Television, Radio 5 Live, Radio 4, and the BBC World Service.

Just as important, established broadcast and print media operations normally command impressive traffic online. The French daily Libération has a print circulation of about 80,000, but Désintox attracts millions of monthly unique visitors online, driven by the newspaper and by a partnership with the TV network Arte, which for five years has included animated, 90-second versions of Désintox fact-checks on its weekly show 28 Minutes. Channel 4 News, noted for its active social media presence, saw nearly three million views for one online video debunking key Brexit-related claims (Mantzarlis 2016a). In contrast, in an international survey conducted by the Poynter Institute in May 2016, many independent fact-checking ventures reported monthly unique visitors in the thousands or tens of thousands.

A second key advantage is the ability to draw on the editorial resources and infrastructure of a larger news-gathering operation. A number of newsrooms have made impressive commitments to fact-checking. At Le Monde, Les Décodeurs began as a two-person blog but now manages a staff of ten producing roughly 15 fact-checks per month, in addition to explanatory and analytical stories. The operation has evolved into the newspaper’s data journalism hub, and includes political reporters but also web developers and data specialists who produce the interactive charts and graphics the site is known for. Similarly, El Objetivo relies on about ten people to research, write, edit, film, and produce graphics for five or six fact-checking segments each week. Perhaps three of these will be featured on the hour-long broadcast, along with investigative segments and in-depth political interviews, while the rest are published online. Each roughly five-minute segment includes video of political leaders making the claim being researched, on-screen graphics laying out the relevant data, and interviews with academic experts, stitched together in a running dialogue between anchor Ana Pastor and the head fact-checker, Natalia Hernández Rojo. ‘It takes all week,’ Hernández said in an interview.

Smaller and episodic fact-checking ventures also benefit from the infrastructure of an established newsroom. Existing news outlets can enter the field quickly and at relatively low cost. For example, the FactCheck series at Ireland’s online newspaper TheJournal.ie began in February 2016 as an experiment to cover the general election campaign. The series was proposed by a Philadelphia-based freelancer, who researches and writes all of the two to four fact-checks appearing each week. ‘I was talking to the editors about the strategy as a whole for the site for the election coverage, and suggested that we should do this,’ said Dan Mac Guill. ‘There isn’t a team, but there is, obviously, a huge amount of support from everybody within the news team.’

Similarly, Der Spiegel has been able to experiment with fact-checking by drawing on its in-house research department. Hauke Janssen launched the online Münchhausen-Check, repurposing a feature that had appeared occasionally in the print edition, after meeting the founder of the US site PolitiFact at a journalism conference. The site was meant to operate only during Germany’s municipal elections in September 2013, but Janssen ran it for more than another year ‘more or less as a hobby’. Münchhausen-Check lapsed in 2015 due to time constraints and, Janssen said, because German media seemed saturated with fact-checking. However, ad hoc fact-checking articles continue to run often in Der Spiegel, and Janssen plans to experiment with the genre again in a more structured way for the 2017 elections.

The NGO Model

As noted, most permanent fact-checking outlets operate outside of traditional newsrooms. Independent and NGO-backed sites are the norm across Eastern Europe, although notable examples also exist in the UK and Italy, for instance. These organisations typically partner with news outlets, and most employ some reporters, but they lack the dedicated editorial resources and reliable audiences that fact-checkers based in media companies can count on. At the same time, independent fact-checking outlets are free of the editorial and business constraints of established media firms and many have proved quite durable.

Many such outlets are projects of established NGOs concerned broadly with strengthening democratic institutions. In the Balkans, for instance, a network of NGOs founded in the wake of civil conflicts in the 1990s has turned its attention to fact-checking over the past several years. Serbia’s Istinomer, or ‘truth-o-meter’, a fact-checking and promise-tracking site modelled on PolitiFact, was established in 2009 by the Center for Research, Transparency and Accountability (CRTA). The project transformed the civil society organisation, which had its roots in a group formed in 2002 to support the democratic transition but quickly grew to more than 20 staffers after launching its fact-checker. Through organisational links and common funders – especially the National Endowment for Democracy – sister sites quickly spread across the region: Istinomjer, a project of Bosnia’s Zašto ne? (Why Not?), a peace-building group begun by student activists in 2002; Vistinomer, from the Macedonian NGO Metamorphosis, which began as an Open Society Foundations affiliate in 1999; and most recently Faktograf, by Croatia’s GONG, originally founded in 1997 as a citizens’ election-monitoring group. ‘The truth-o-meter was the glue for our network,’ said Dušan Jordovic, a CRTA project manager and one of Istinomer’s creators.

A similar pattern can be seen in the post-Soviet states. FactCheck Georgia, founded in 2013, is a project of Georgia’s Reforms Associates (GRASS), a ‘policy watchdog and think tank’ established by a group of former government ministers and civil servants the year before. In Ukraine, two fact-checking outlets have recently been launched by civil society groups which grew out of the 2013 ‘Maidan Revolution’. VoxCheck was unveiled in December 2015 by VoxUkraine, an online economics and policy hub focused on promoting economic reforms. And with help from GRASS, the Kyiv-based Ukrainian Team of Reformers, which operates a professional school for civil servants, opened FactCheck Ukraine in May of 2016.

Other outlets are completely independent or housed in a purpose-built charity or NGO. The UK’s Full Fact, founded in 2010, is a registered charity with a board of trustees that includes journalists as well as members of the country’s major political parties. Full Fact has a staff of 11 checking roughly 40 claims per week by political figures as well as the media. Italy’s Pagella Politica (or ‘political report card’) was launched in 2012 by nine young volunteers from the professional and public policy worlds. The site gained visibility, and vital financial support, with a contract to produce fact-checking for Virus, a public affairs programme on RAI; it is registered as a small business in order to be able to sell services to the media. In Turkey, a network of political science PhD students and graduates – the founders met during an internship in Washington, DC – launched Doruluk Payı (or ‘share of truth’) in 2014, motivated by misinformation about the Gezi Park protests of the previous year. The founders established an umbrella NGO, the Dialogue for Common Future Association, in order to secure foundation funding.

Many independent fact-checkers depend on formal or informal ties to universities. Slovakia’s Demagog was founded in 2010 by a pair of political science students at Masaryk University in Brno, and quickly spread to sister sites in the Czech Republic and Poland. (A Hungarian version of the project is now inactive.) All three operations rely heavily on student volunteers, who gain research experience and in some cases earn credit at their universities. Faktabaari, a Finnish site launched in 2014 by an NGO called the Open Society Association, has relied on student journalists from Haaga-Helia University. In Ukraine, students and faculty of the Kyiv Mohyla School of Journalism founded the ‘counter-propaganda’ site StopFake in 2014 in response to the Russian occupation of Crimea. The school supplies space and equipment as well as student volunteers to the fact-checking outlet, and has also incorporated fact-checking into its curriculum. ‘It was kind of a perfect match,’ said Yevhen Fedchenko, StopFake’s director and a faculty member at the journalism school. ‘It was always important for StopFake to have the umbrella of the school because it provided a lot of credibility. And for the school it was also great because we are a very practical and hands-on school, so we’ve always been looking … to implement what we teach, practise what we preach.’

An outlet with more formal academic ties is The Conversation, which relies on professional editors to curate analytical articles and fact-checks written by academic experts on the faculty of major universities around the world. The project first launched in Australia in 2011 but now has dedicated sites in the US, the UK, South Africa, and France. The British and French sites are registered non-profits and rely on financial support from a network of dozens of university partners in each country.

Mission and Identity

Arraying fact-checkers according to organisational ties helps to shed light on a diverse landscape. Outlets attached to established news organisations enjoy a distinct advantage in reaching wide audiences cost-effectively. However, some smaller, independent groups also identify as news outlets. Meanwhile, wide contrasts in the media and political environments in which fact-checkers operate affect how they understand and perform their work.

In terms of mission and identity, fact-checkers in Europe can usefully be divided into three categories: reporters, reformers, and experts. These ideal types overlap in practice, and how practitioners describe their work may vary even within the same organisation. But these three categories offer a useful lens for understanding how fact-checking challenges traditional views of professional journalism.

Reporters

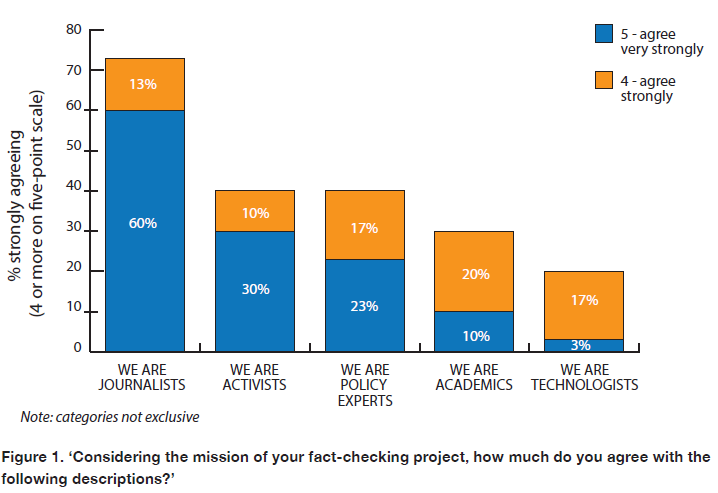

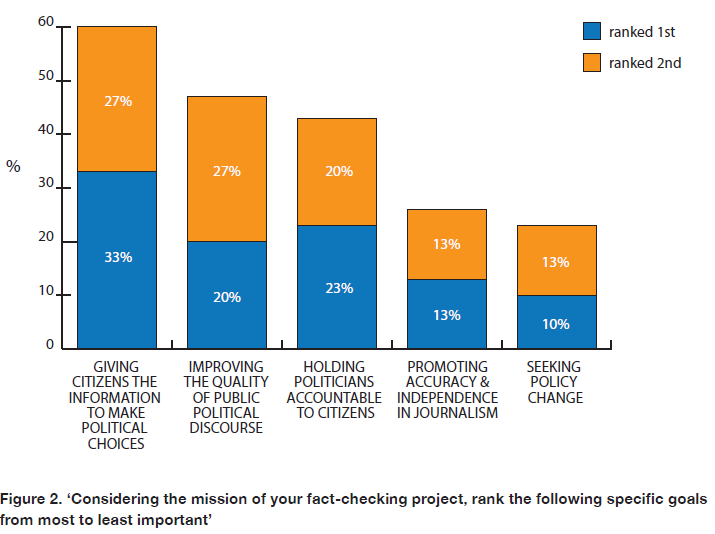

Practitioners in this category, whether based in a traditional newsroom or not, see themselves mainly as journalists and describe the mission of fact-checking in journalistic terms, as a vehicle to inform the public. In our survey, nearly three-quarters of organisations responding agreed strongly (four or more out of five) with the statement ‘we are journalists’, the most popular response. (However, categories were not exclusive; some also strongly endorsed other definitions, such as ‘activist’ or ‘policy expert’.) Asked to rank specific goals for their fact-checking work, a third identified providing information to citizens as the most important, while nearly one quarter chose holding politicians accountable. Just over half identified journalism as the ideal professional background for fact-checking.

Fact-checkers in this core journalistic group see the job as mainly explanatory, and may be wary of the activist spirit sometimes associated with the enterprise. ‘The fact-checking is … often a pretext to allow people to go into complicated information, to go and read it and to interest them in it,’ said Samuel Laurent, head of Le Monde’s Les Décodeurs. Dan Mac Guill, the resident political fact-checker at Ireland’s TheJournal.ie, explained that he proposed the fact-checking project as a way to round out the online newspaper’s election coverage. ‘I’ve done a lot of data-driven work and … some investigative reporting,’ he said.

For me, the main drive behind it is to inform readers. It’s not an activist platform. Certainly transparency and all of those things play a part, and naturally I would be in favour of more [rather] than less transparency … But it’s not a campaigning platform as such … For me, the main motivating factor is to try and just essentially help readers sort through things, since they don’t have time or maybe the access to resources or the skills to sort through claims that have been made.

StopFake, the Ukrainian outlet launched in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea, has wrestled with the question of how to balance journalistic principles with the reality of combating a deliberate and organised propaganda campaign. The idea for the site took shape just weeks into the conflict, at a meeting of 30 to 40 students, academics, and professionals eager to take action. The project had a clearly activist bent. ‘We started as a volunteer site and as a response to a crisis situation … And people came motivated by the desire to help Ukraine,’ explained director Yevhen Fedchenko. However, StopFake has since deliberately professionalised, he maintains, by hiring paid staff, developing a rigorous methodology, and adopting a neutral approach that includes checking pro-Ukrainian media:

We really went through all these kinds of discussions and through internal transformations to have this project quite purified of ideology, any kind of mission. We really decided that we need to be very neutral, based on journalistic standards.

At established news organisations fact-checking is often tied to data journalism efforts. As noted, Les Décodeurs has become a hub for analytical, data-driven reporting at Le Monde; Laurent described the ‘three pillars’ of the site as explanatory journalism, data journalism, and fact-checking. Similarly, Spain’s El Objetivo advertises its focus as data journalism and in-depth interviewing; its fact-checks very often focus on statistical claims related to the economy, immigration, and similar areas, and turn on detailed analysis of public datasets. Inspired in part by El Objetivo, the Spanish newspaper El Confidencial launched La Chistera (‘the top hat’) in late 2015 based on a proposal by its three-person data journalism team, which now produces one or two fact-checks each week (and more after major debates) in addition to its usual analytical work. Daniele Grasso, head of the data team, said fact-checking was a natural fit: ‘We daily have to work with data. So when we hear it we don’t know [right away] if the number that the politician is quoting is right or wrong, but we know perfectly which data set it came from.’

Other news organisations associate fact-checking with investigative reporting. This reflects in part the different constraints these outlets face in their work. For instance, fact-checkers across Eastern Europe remarked on the amount of digging often required to obtain public information; many rely on freedom-of-information requests for even routine economic statistics. ‘We view [fact-checking] as touching on investigative journalism and inspiring investigative journalism,’ said Filip Stojanovski, founder of Macedonia’s Vistinomer. The site is housed in an NGO concerned with issues from good governance and human rights to e-waste, but operates as an independent newsroom. One of its missions is to recover data which disappears from the online sphere; this year it published a large archive of leaked wiretaps implicating top officials in a major corruption scandal. ‘In this sense, we are the keepers of public record, providing some sort of materials not just for this moment, but for the years ahead,’ Stojanovski said.

Internews Kosova, an NGO which promotes media development and independent journalism, practises an unusual hybrid of fact-checking and investigative journalism. With the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, Internews Kosova produces a pair of widely viewed public affairs programmes, Justice in Kosovo and Life in Kosovo, which feature political debates and original reporting, as well as Kallxo.com (Tell.com), an online platform for citizens to report corruption, crime, and similar complaints. The combination allows debate moderators to fact-check politicians on the air with information gleaned by the investigative teams. ‘Investigative journalism plus fact-checking equals an interesting TV programme,’ said Faik Ispahiu, executive director of Internews Kosova. ‘It is my personal belief as a producer that fact-checking alone, without investigative journalism, without a proper media approach, is not enough.’

Adhering to a journalistic worldview does not prevent fact-checkers from being critical of their own profession. On the contrary, reporters involved in this work often suggest that it represents a much-needed advance. This is true not only for outlets like Internews Kosova, which aim explicitly to bolster independent media, but also for many journalists in wealthier democracies. For instance, at a 2014 meeting of fact-checkers the Reality Check reporter for the Guardian complained that only now was she doing ‘what I originally got into journalism to do’. Natalia Hernnádez Rojo, in charge of fact-checking on El Objetivo, suggested that the programme offered an example of non-partisan accountability reporting in a country whose news media are divided along political lines. At Le Monde, Samuel Laurent suggested that fact-checking ‘goes against the traditional vision of French journalism, which is sometimes too close to people in power’ – and more broadly against a literary, less fact-centred strain of journalism that still exists in France. ‘There is a form of journalism, I do not know how to define it, that is a little close to the bone and not very scientific, let us say,’ he argued.

Reformers

The second category, reformers, describes outlets which understand fact-checking primarily in activist terms, as part of an agenda of political reform. These outlets may tie fact-checking quite closely to other programmes and sometimes use it to promote specific policy changes. Many openly embrace an activist identity. In our survey, 40% of responding organisations agreed strongly with the statement ‘we are activists’. While only a small fraction selected ‘seeking policy change’ as a top priority, 43% ranked either ‘holding politicians accountable’ or ‘improving the quality of public discourse’ as their primary goal.

As noted, most fact-checkers in the Balkans and the former Soviet Union are based in NGOs concerned with democratic institution-building: fighting corruption, promoting civic engagement, and establishing a culture of political accountability. FactCheck Ukraine offers a typical example. ‘We see fact-checking as part of the project of the civil reform movement,’ said project head Igor Korkhovyi. ‘The main idea of our fact-checking is to involve average people into the process of accountability of officials, and monitoring their rhetoric and combating populism.’ The project is attached to a ‘civil and political school’ which offers classes to both public- and private-sector employees with the goal of building a professional administrative sector.

Outlets with a reformist outlook often explicitly reject the journalistic role as too constraining. The three sites in the volunteer-driven Demagog network embrace an activist identity even though they lack a specific policy agenda. ‘You’re doing something proactively to improve the situation. That, to me, is activism,’ explained Petr Gongala, one of the founders of the Czech site. According to Łucja Homa, a former coordinator of the Polish site who now works in the office of Krakow’s mayor, one of Demagog’s most important impacts is on volunteers themselves, producing a new generation of activists:

Some of our volunteers are going to jobs in the NGO sector. They hadn’t thought beforehand about joining the NGOs. But after working for Demagog, they decided that being a social activist is much more interesting than doing some other job. And that is very cool.

Other groups turned to fact-checking after long histories of organising protests and demonstrations. ‘We’ve never identified as journalists,’ said Aida Ajanovic, a researcher with Bosnia’s Istinomjer. The group’s parent NGO first gained attention for an annual ‘peace caravan’ uniting activists across the Balkans; today its core mission is using technology to combat ‘ethnopolitics’ and promote an ‘accountability-based society’. In addition to checking political claims, the group publishes annual reports tracking the progress of pre-election promises made by politicians at every level of Bosnian government.

Many NGOs emphasised the tight links between fact-checking and other projects. For instance, Serbia’s CRTA developed its OpenParliament platform for digital transcripts partly in response to the needs of Istinomer’s fact-checkers. Conversely, the site’s editorial agenda, overseen by a ‘political director’, reflects signature programmes like CRTA’s Voter Proclamation project, which secures signed pledges from party leaders to support a list of policies relating to transparency and the rule of law. In one high-profile campaign, CRTA forced the resignation of Serbia’s Minister of Education, after an epidemic of cheating on national exams, with a combination of street protests, a nationwide petition, a series of hard-hitting videos, and roughly 40 fact-checks relating to the affair. The site hires journalists as well as activists but always looks for ways to move from the ‘information phase’ to the ‘action phase’, explained project manager Dušan Jordovic.

Similarly, Romania’s Funky Citizens, an NGO founded in 2012 to build ‘research-based, data-driven online advocacy tools’, first became known as a budget watchdog and for its ‘bribe market’ project, which applies market principles to hold down the costs of bribes for public services. During controversial 2014 elections the group became involved in election monitoring and also took over an ad hoc, volunteer-driven ‘checkathon’ project to launch Factual.ro. The site’s fact-checking was instrumental in a high-profile campaign to protest inadequate polling stations at Romanian embassies around the world, which eventually resulted in a criminal investigation. According to the group’s president Elena Calistru, the fact-checking project draws directly on experience gained in other programmes, especially its budget research, but also feeds back into those efforts, helping to position the NGO as a ‘reference point’ for a network of political campaigns and organisations. She explained,

I actually think that, at least in this side of the world, it’s better to have an NGO doing fact-checking, because you can follow up what you’ve discovered there easily … It’s quite easy for us, we have the knowledge, we have the information … Or at least we know where to look for the data, much easier than, I don’t know, normal journalists.

Crucially, for many of these organisations, independence from mainstream news organisations is seen as a vital source of credibility. In our poll, only 43% of fact-checkers rated the news media where they work as very democratic (five on a five-point scale). In interviews, nearly every practitioner in Eastern Europe described major media outlets as to some degree partisan, corrupt, and unreliable, dominated by powerful business and political interests. ‘In Poland, when you say you are a journalist, no one will trust you, because basically the biggest media is not very reliable for people,’ said Demagog’s Homa. ‘We are branding ourselves as activists. Like, a watchdog organisation.’ Many lamented the decline of serious journalism over the past decade in the face of partisan, populist outlets. ‘Serious, normal, decent media was almost replaced by yellow, by media which has been quite racist,’ said Paata Gaprindashvili, director of FactCheck Georgia. Activists and NGO officials often highlighted their non-profit status as a crucial distinction, arguing that media companies only pursue fact-checking as long as it makes money. As Istinomer’s Dušan Jordovic suggested,

We will never cut the truth-o-meter in Serbia unless we go bankrupt. And even then we will try to have a website and to do something, because we believe in it, not to have a profit … I am not saying that media fact-checkers are evil or something like that … [But] we look on the truth-o-meter in Serbia like our child, so we are going to do everything for it.

However, it is important to stress that the lines between activists and journalists can be blurry, and fact-checkers in the same organisation may see their roles differently. Many NGOs focus on bolstering independent media as an element of building democratic institutions, and some have come to understand their own work in journalistic terms after becoming involved in fact-checking. ‘We don’t see ourselves as journalists, because we are not. But we are trying to contribute to the journalistic scene in Turkey by providing fact-based content,’ said Baybars Örsek, a founder of Turkey’s Doruluk Payı. Started by a group of political science graduates, the site now provides training in fact-checking and ‘digital verification’ to media and journalism students. FactCheck Georgia similarly promotes fact-checking by Georgian journalists, and recently launched a print newspaper to bring its fact-checking to citizens who are not online. Gaprindashvili, a former diplomat, said he has started to see his project in a new light:

We are more and more understood and accepted as a media … I never associated myself before with journalism. But I personally realised that all of a sudden I had become a journalist. All these activities, what we’ve been practising, that is a part of journalism, that is a new kind of journalism.

Experts

The third category, experts, is the most difficult to define with sharp boundaries. All dedicated fact-checking organisations seek to establish themselves as authoritative sources of information on often complex areas of public policy. However, the label helps to set apart outlets which place a particular emphasis on their own domain expertise or distinctive methodology, positioning themselves as something like a think tank rather than as journalists or campaigners.

In our survey, 40% of organisations responding agreed strongly with the statement ‘we are policy experts’, while roughly one-quarter defined themselves as academics. More than half saw either politics or economics as the ideal educational background for a fact-checker. Many of the parent NGOs of fact-checking outlets rely on legal, economic, and policy experts in pursuing political or policy reform. Despite its activist orientation, for example, Romania’s Funky Citizens has positioned itself as a leading domestic authority on budget analysis, staff said, and offers training to other NGOs as well as government officials. Similarly, FactCheck Georgia calls itself a ‘non-partisan, non-governmental policy watchdog and think tank’.

Some organisations avoid both activism and journalism as labels. The Italian site Pagella Politica is an instructive case. Its founders, all volunteers at the outset, came from professional backgrounds in research and policy. Initially the site had nobody in an editorial role – volunteers chose facts to check based on their own expertise in distinct areas such as economics and law, prominently advertised on the site. As Alexios Mantzarlis explained,

We were all researchers or consultants for international organisations. We came at it from kind of a nerdy, wonky place of, ‘Hey, claims out there do not reflect statistics that we can find with our background or expertise, why don’t we do something about it.’ … We wanted to inject a bit of objectivity into Italian public policy discussion.

Other sites formally distinguish editorial and research roles. The editor of Ukraine’s VoxCheck is an experienced business journalist. But the site publishes only two or three deeply researched fact-checks per month, focusing narrowly on economic questions and drawing heavily on VoxUkraine’s advisory board of professional and academic economists, who vet every article. The Conversation applies the same principle on a much larger scale: academics based in a network of major universities produce the site’s fact-checks and other articles, which are curated and edited by professional journalists. Every fact-check undergoes a blind peer review and is published with a comment from another academic. ‘The strength of The Conversation is that everyone who writes for us is an expert,’ deputy editor Megan Clement explained. ‘We’re not a campaigning organisation. Our mission is to raise the quality of public debate and to put high-quality information into the public domain.’

The UK’s Full Fact offers a distinctive example of an independent, single-purpose fact-checking outlet positioned as a think tank. Founded in 2010, the organisation investigates claims by both politicians and the news media and is unusual in placing a heavy emphasis on actively seeking corrections. As its mission statement explains, ‘we … push for corrections where necessary, and work with government departments and research institutions to improve the quality and communication of information at source’. The organisation has also provided testimony to government inquiries relating to accuracy in the media. These interventions may count as a narrow kind of campaigning, but its mission requires Full Fact to strictly separate itself from both news outlets and political groups and causes, even forbidding staff from expressing political views. According to director Will Moy, the site relies on some journalists in its fact-checking work but increasingly seeks researchers with domain expertise in the areas they cover.

Methods

Independent fact-checkers follow the same template in their work, broadly speaking. Nearly every practitioner interviewed for this report spoke of the need to check claims from across the political spectrum, to seek out reliable data and independent experts, and to be transparent in their work. 5 Many outlets publish methodologies or statements of principle which reflect these basic elements; globally, 35 fact-checking groups from 27 countries signed a common code of principles in September 2016 (Kessler 2016). This is a clear example of how fact-checking is being institutionalised – a growing number of outlets across the world not only self-identify as fact-checkers but also explicitly commit to shared norms and routines (see Graves 2016a). Within that broad framework, however, a number of important differences in approach can be identified. These variations reflect contrasts in the mission and identity of fact-checkers as well as the diverse range of political environments in which they operate.

Meters

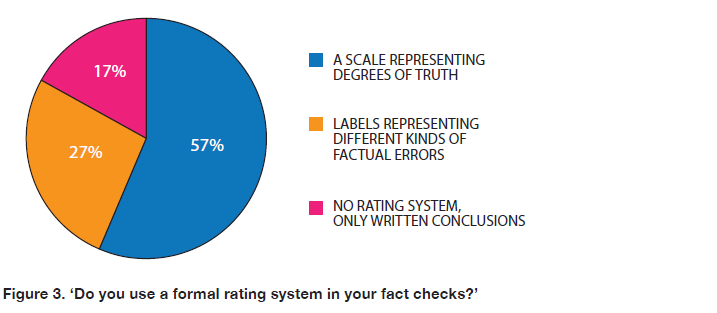

A major divide which does not seem to track organisational or professional boundaries concerns the use of rating systems to assess political claims. In our survey, close to 60% of European outlets indicated that they rate claims along an ordinal scale representing degrees of truth. This includes news outlets, such as TheJournal.ie, El Confidencial, and El Objetivo, as well as many independent and NGO-backed sites. Scales used range from simple verdicts – true, mostly true, half true, etc. – to colourful, sometimes comical meters. Pagella Politica’s ratings run from ‘vero’ to ‘panzana pazzesca’, which editors have translated as ‘insane whopper’. El Confidencial’s La Chistera uses a four-point, magic-themed scale which assigns a green checkmark to true statements, a yellow or orange rabbit to imprecise or false ones, and a red unicorn to outright fabrications.

Other outlets – just over one-quarter in our survey – assign categorical labels to claims but don’t rate them on a scale. ‘To be honest, I can’t really understand how the scale would work,’ said Zdenek Jirsa, of the Czech Republic’s Demagog. ‘Because, you know, how can you say the politician is 75% right?’ The site initially based its rating system on its Slovakian predecessor, which assigns one of four labels to each claim: true, false, misleading, and unverifiable. At the time of our interview, however, the Czech researchers were preparing to add a new category, inexact, to capture minor errors. ‘We were sometimes judging things as true, even though they were slightly off,’ explained Petr Gongala, the site’s official methodologist.

As that suggests, fact-checkers sometimes modify their methodologies in practice, tweaking their rating system or letting particular verdicts fall into disuse. Finland’s Faktabaari began with a five-point scale but later simplified it to just three ratings. In Bosnia, Istinomjer uses a three-point scale but researchers said they never apply the middle verdict, half-true; instead, fact-checks which don’t result in a decisive ruling are published as unrated analysis pieces. Le Monde initially used an ordinal truth scale but switched to categorical labels – faux, imprécis, exágeré, trompeur – due in part to complaints from readers. ‘We did not remain obsessed over the matter of a minor rating of true or false because that irritates people a lot, and it is a shame because they lose the background of the plot,’ said Samuel Laurent.

A handful of fact-checking organisations reject the use of ratings altogether. Globally, one-fifth of fact-checkers use no rating system, according to the Duke Reporters’ Lab; in our survey of European fact-checkers the figure was 17%. Examples include news sites, like the Guardian, the BBC, and France24, as well as independent outlets such as Full Fact and The Conversation. Full Fact began with an ordinal truth scale – a five-point system using the group’s logo, a magnifying lens – but later abandoned it. Founder Will Moy has argued forcefully against the use of ‘inherently dodgy’ ratings systems as needlessly reductive (Kessler 2014). The move away from rating claims also accords with what the organisation calls a ‘less combative, more collaborative approach to factchecking’:

Our mission is to ensure that the public has access to the best possible information, so we work with decision-makers and opinion-shapers, as well as factchecking them, to help them to be more accurate and improve the overall quality of public debate. (Full Fact 2016)

Selecting Claims

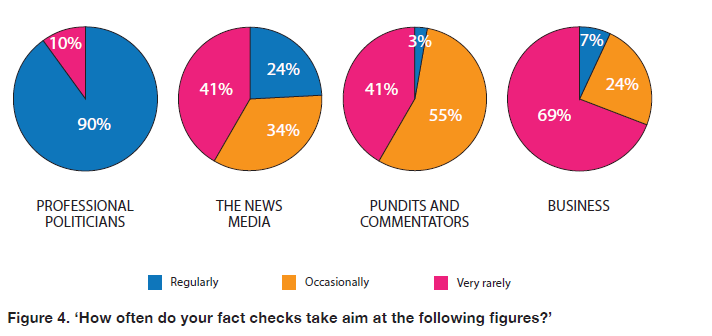

Fact-checkers also vary in their approach to selecting claims to investigate. Like their peers globally, most fact-checking outlets in Europe focus their efforts on political actors. In our survey, 90% indicated they regularly check claims by politicians; most outlets target journalists, pundits, or other public figures only occasionally or not at all. However, Ukraine’s StopFake focuses almost exclusively on the media, and sites such as Full Fact, Finland’s Faktabaari, Northern Ireland’s FactCheckNI, and Macedonia’s Vistinomer systematically fact-check the news media. In all, just under one-quarter of organisations surveyed regularly target the news media, and another third do so occasionally.

While all fact-checking organisations scan the news to find political claims to check, several factors seem to inhibit more robust media fact-checking. First, many organisations indicated that resource and staff limits keep the focus on politicians. Bosnia’s Istinomjer published a media fact-check only once, to challenge widely reported false claims about the behaviour of protesters at a 2014 demonstration. (The piece included a disclaimer explaining that the media in that case were doing the bidding of politicians.) The fact-check was the most widely read piece in Istinomjer’s history, but the group remains reluctant to check the media regularly. ‘We wouldn’t have time,’ said Alisa Karovic, pointing out that in addition to checking political claims the group also tracks thousands of pre-election promises each term. ‘We don’t think we would have time to do it systemically and consistently, because we’re barely keeping track of the [political] statements and pre-election promises.’

Checking the media also carries particular risks. First, for professional journalists it may be awkward to subject their peers to scrutiny. While the Guardian’s Reality Check blog regularly targets other newspapers, editors at both Der Spiegel and Le Monde said this did not seem like an appropriate mission. (However, Le Monde has increasingly focused on debunking false rumours and doctored photos which circulate on social media – a particularly vital mission after incidents such as the two major terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015.) Meanwhile, independent or NGO-based outlets depend on the media to amplify their own fact-checking and, especially where media–political ties are strong, are reluctant to provoke negative coverage. Researchers at Serbia’s Istinomer have debated whether to fact-check the media but worry about angering ‘egomaniacs with microphones’, as CRTA programme director Raša Nedeljkov put it, and becoming the target of a smear campaign. Full Fact has focused on claims in the press from the outset but also felt the need to be cautious as it began to seek corrections more actively. ‘We were all wary of pissing off the papers, especially at the beginning,’ said Phoebe Arnold, head of communications and impact for the group.

All fact-checkers struggle with the problem of maintaining party balance in their work, to establish their independence, while also responding to shifting political circumstances and trying to focus on the most consequential claims. The supply of firm factual claims diminishes after elections and in moments of national unity. Doruluk Payı was able to publish only a handful of fact-checks in the weeks after the July 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, because normal political debate was effectively suspended as politicians rallied around the state, according to co-founder Baybars Örsek. Several fact-checkers remarked on the difficulty of finding interesting factual statements to investigate from opposition parties, which often favour vague promises and empty platitudes. ‘They’re not proposing policies as much as they’re criticising,’ explained Radu Andrei, of Romania’s Factual.ro. As Jelena Manojlovic, a fact-checker with Serbia’s Istinomer, complained,

They’re becoming more and more skilled, rhetorically skilled, to avoid concrete promises and statements, it’s just something in the clouds… So there is nothing to be checked. And I believe they do it on purpose. It’s better to tell something stupid like that, than to risk and to say something that might be checked.

Some organisations take a methodical approach to maintaining political balance. Doruluk Payı, which focuses on claims from members of Turkey’s Grand National Assembly, prominently displays the share of fact-checks directed at each political party alongside the party’s current share of parliamentary seats. The point is not to force the ratios to match exactly – the ruling AK party receives disproportionate attention – but ‘to show people that we don’t take sides,’ explained Örsek. The site’s statistics page also includes charts detailing each party’s performance on its five-point truth scale, which it compiles into monthly reports on the state of political discourse. Full Fact, meanwhile, explains that before major elections it considers its resources to decide which major parties it will be able to focus on; for 2015 these were the Conservatives, Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and UKIP. The group also guides its core coverage areas based on the Ipsos MORI index of major issues facing Britain.

The Demagog sites in Slovakia and the Czech Republic put the greatest emphasis on selecting claims in a way that allows for statistically valid comparisons between parties. Rather than choosing claims from the week’s news, the two outlets focus on televised debates which air every Sunday and are an important political institution in both countries. (In contrast, the Polish version of Demagog draws statements mainly from political interview programmes which air on weekday mornings.) To avoid selection bias, the fact-checkers purport to verify every single discrete factual statement made during the debates. At the Slovak site, for instance, a senior analyst examines the debate transcripts as soon as they become available, to identify claims and assign them to a pool of roughly 15 volunteer fact-checkers via a custom-designed content management system (CMS). Each checker then has 24 hours to verify about five or six claims, so that the results can be published by Tuesday. Before major elections, when debates are held more frequently, the operation might add as many as 500 claims to its database over two or three weeks. That database now includes more than 12,000 fact-checks, most quite concise, categorised by speaker, party, topic, and level of accuracy. Researchers plan to use this data to study longer-term shifts in public discourse.

Calling the claimant

Fact-checking organisations also vary in a number of basic research procedures, despite a consistent focus on seeking authoritative data. One basic difference concerns the question of whether to contact the author of the claim being investigated. At least one news outlet, TheJournal.ie, appears to contact the claimant more or less as a matter of course to clarify the statement being made and ask for supporting evidence. (This is also common practice among leading US fact-checkers, for instance.) Other journalists suggested that they try to call the statement’s author only when circumstances seem to demand it. As Daniele Grasso of El Confidencial said

I mean, before giving a unicorn to the chief of the opposition party during the election, you have to think about it, because it’s huge. So we contact the press people and we ask their explanation and then we decide. During the electoral campaign, we were a bit more careful with that, and … maybe we prefer to wait one day or two before publishing the post.

However, most European fact-checking outlets, including many based in news organisations, rarely or never contact the author of a claim while researching it. Many suggested that the extra step seemed redundant. ‘The statements we take are usually pretty clear and so you don’t need that kind of clarification,’ said Aida Ajanovic of Bosnia’s Istinomjer. Petar Vidov of Croatia’s Faktograf agreed: ‘I find it unnecessary. I know that some other outlets consider it good practice to contact the people they’re fact-checking, and to get further elaboration from them,’ he said. ‘But when you’ve got a statement that is very clear … I don’t feel the need.’ Others worried that it would invite a pre-emptive attack. Olena Shkarpova of VoxCheck said she tries to avoid alerting important political figures that a fact-check is in the works:

Our politicians are very influential and they have a lot of power, a lot of money behind them. And we are very strong only in terms of our intellect, intellectually, and that’s it. I mean, people trust us. So we have reputation, [but] this is all we have … We don’t have money, and strong people, powerful people behind us. Every article is a bit scary for me.

Use of Experts

nother important methodological difference relates to the use of outside experts. Many outlets regularly include expert voices in their work to help interpret data and lend force to the fact-checkers’ verdicts. For instance, the five- to eight-minute fact-checking segments on El Objetivo typically follow a template which begins with video of politicians repeating a questionable claim, proceeds to a review of the relevant data via colourful, animated charts and tables, and then features one or more scholars putting the data in context. Other journalists reported that they quote experts when time and space permit. ‘When you have only two hundred or three hundred words, and online maybe four hundred, then it’s more difficult,’ said Dr Hauke Janssen of Der Spiegel. The Serbian site Istinomer has made a concerted effort over the past year to include more expert voices in its work, but researchers said some sources prefer to remain off the record.

Several fact-checkers remarked on the dearth of reliable independent experts in the environments where they operate. ‘It’s so difficult to identify who are the non-partisan experts,’ said Paata Gaprindashvili of FactCheck Georgia. ‘But nonetheless, I encourage my fact-checkers to take interviews from the experts.’ Bosnia’s Istinomjer rarely interviews outside experts, for the same reason. ‘If you do a fact-check with experts, then there’ll be somebody who can provide another opinion because everything is divided in our country, [and] so are the experts,’ said Damir Dajanovic. ‘So it would not yield the results we probably seek.’ Others rely on trusted experts in their research but do not generally quote them. Full Fact relies on public data in its fact-checks but its researchers frequently conduct off-the-record interviews with sources in academia and government. VoxCheck, Doruluk Payı, and Factual.ro all maintain networks of professional and academic experts who guide the fact-checkers in their analysis but don’t usually appear in the text.

Finally, practitioners who don’t rely on experts argued that hewing narrowly to factual claims reduces the need. ‘I would say that 99.9% is done by us,’ said Zdenek Jirsa, of the Czech version of Demagog, emphasising the expertise of the site’s volunteers and the oversight provided by senior analysts. ‘You know, the beauty of factual statements is that it’s a fact. You don’t need somebody actually quoting that. It can be, maybe, useful when you have something related to law, which requires interpretation.’

Impacts and Media

As discussed above, fact-checkers define their goals in different ways, placing different levels of emphasis on informing citizens, holding politicians accountable, seeking policy change, and so on. In practice, however, these concerns blend together; fact-checks which draw a lot of attention from the public and the media are more likely to yield other political impacts. All of the groups reviewed in this report share a broad concern with promoting truth in public life – and all acknowledge that this is difficult work which rarely yields dramatic or permanent breakthroughs.

Political impacts

Politicians generally ignore fact-checkers. Most organisations interviewed for this report could point to isolated cases in which a politician appeared to abandon a false claim after it was debunked. On rare occasions the person being checked will acknowledge the error publicly. In Spain, for instance, Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias graciously thanked El Objetivo on Twitter after the programme challenged an inflated figure he had been wielding about the value of the country’s arms sales to Israel, saying he misread the data. ‘Sometimes they’re, “Okay, I was wrong. I used the old data”’, said Patrycja Braglewicz, a coordinator for Poland’s Demagog. ‘But it’s really rare still. Too rare.’ Meanwhile, prominent politicians often develop a reputation for being impervious to fact-checking. ‘Take the example of Nicolas Sarkozy,’ said Samuel Laurent of Le Monde:

There are errors stated, false things which he has said for ten years – i.e. it is not one verification, it is six, seven, eight, ten, that never prevented him from continuing to say them. In any case, he knows that his listeners, his flocks, will not get their information from me to check if what he says is true or false. It is also the problem with Trump. I looked the other day at the number of fact-checks that there have been on Trump, that does not prevent him from climbing in the polls.

In some cases politicians respond to a fact-check by going on the offensive. After challenging exaggerated claims about Italy’s punitive tax rates, Pagella Politica came under attack from the then-head of the Chamber of Deputies, who was also the leader of Forza Italia, Silvio Berlusconi’s party. ‘He came at us several times, both on Twitter and with several press releases,’ said Alexios Mantzarlis. ‘And actually, that was one of the most fun times we ever had, because there was nothing to it, and we came back with, you know, “Where are your data?”’ In Bosnia, Istinomjer provoked a counterattack from the prime minister of the Republic of Srpska after challenging her claim, on the eve of proposed rate increases, that residents enjoyed the lowest electricity bills in the region; the Srbskan electrical utility even held a press conference to question Istinomjer’s research, underscoring how politically charged the issue was. ‘In terms of impact, yeah, that was a big one because you had the ruling party clearly calling the electricity company,’ recalled Aida Ajanovic. Poland’s Demagog has sometimes been criticised as ‘just a bunch of students’, said Braglewicz. Les Décodeurs has weathered criticism from an old guard of journalists and political commentators, according to Laurent, ‘who say that we ourselves are tainted’.

Most often, though, political figures simply disregard fact-checking, or acknowledge only those items that support their own claims or challenge their opponents. ‘No one ever corrected themselves on the basis of what we wrote,’ said Alisa Karovic, of Bosnia’s Istinomjer. ‘The reactions have been very few, because I think they quickly understood and learnt that the best way for them to react is not to react.’ She suggested that a few high-profile confrontations, like the one over electricity rates, taught politicians ‘that it’s best that they keep quiet’. Olena Shkarpova of VoxCheck reported that only one politician had ever responded directly to a fact-check, though the group’s work appears to be widely read among Ukraine’s political elite. ‘I think that all politicians read our articles, at least their press people do, because all of them know VoxUkraine,’ she said. ‘They read, but they don’t express anything.’ Matúš Sloboda, project manager for Slovakia’s Demagog, echoed the point. ‘We have information that every single party is really reading our analyses. They have sometimes special teams reading our analysis,’ he said. ‘But they react pretty rarely.’

Some practitioners suggested that public figures seem to word their arguments with slightly more care once fact-checking becomes established. In Slovakia, Demagog’s statistics indicate that politicians may be reacting to the scrutiny of their Sunday debates: the average share of true statements in each debate has risen from less than 55% in 2010 to about 64% today. (However, because the share of unverifiable statements has also declined, this may simply suggest that the fact-checkers are getting better at their jobs, Sloboda noted.) French politicians sometimes say fact-checkers have made them more cautious, according to Cédric Mathiot of Désintox. But he pointed out that political rhetoric was wilder than ever during recent elections, despite ubiquitous fact-checking:

In 2012, almost every newspaper had a fact-checking section during the campaign … And it had very little impact, in fact, because I believe that during the campaign period, political leaders don’t care much that some media analysis declares what they say to be false, what is important is to continuously argue on news channels, to hammer home messages.

The most notable instances of a direct influence on public discourse may occur when fact-checkers can claim an institutional role in organising forums for political speech. For instance, one article by Poland’s Demagog provoked a public argument between the current and former ministers of justice; the disagreement led to the scheduling of a special debate about Polish courtroom procedures which Demagog was asked to fact-check. ‘They said, “You started this whole thing, it’s your fault, so fact-check it right now because someone has to do it”,’ said Łucja Homa. Pagella Politica’s arrangement with the RAI political discussion programme Virus allowed it to fact-check politicians on the air, forcing them at least to acknowledge its work. Similarly, Faik Ispahiu suggested that the weekly debate programmes produced by Internews Kosova have become a kind of political institution, obliging politicians to submit to on-air fact-checking. ‘Basically in Kosovo, there is a rule that if you want to become a politician, you need to get the fire crucifixion of our journalists.’ This allows for unusually sensational confrontations, most notably when a panel of public officials was led into declaring that they had no outstanding electricity bills – and then each was confronted on camera with their actual debts (see Mantzarlis 2016a).

Rules governing public information and records offer a vital institutional anchor for fact-checking. ‘When I first read that the UK has a Statistics Authority that you can appeal to to get ministers to correct their claims, I think I wept,’ said Alexios Mantzarlis. As noted, especially in Eastern Europe, NGO-based fact-checkers both rely on, and actively seek to strengthen, such mechanisms – in part by putting them to use. ‘We are using a lot of freedom of information requests, always officially asking for information from public institutions,’ said Istinomer’s Dušan Jordovic. ‘If they don’t answer us in two weeks, then we can appeal to our public information trustee.’ For these groups, putting existing rules into effect and helping to build a culture of practice around them is itself an important impact.

Full Fact has similar concerns in the UK, despite the country’s unusually robust press and parliamentary complaints architecture. The group has reported avidly on the Statistics Authority and on the redesign of press regulation in the wake of the Leveson Inquiry which ran from 2011-2012; it also offered testimony for a high-profile report from the BBC Trust to improve policies for reporting and correcting statistics at the public media company. Full Fact was one of the first groups to regularly file third-party complaints to press regulators, helping to establish the practice, according to Phoebe Arnold:

When we first started using a lot of those mechanisms, they were sort of completely dormant, and they just seemed kind of there for show. But it’s only through continuing to use them, and to escalate when nothing came of using those mechanisms to the next level, that they actually started to warm up and kick into practice … We were kind of representing the idea of accuracy rather than ourselves. And I think that was quite a strange shock to the system for a lot of papers, and the press regulator as well.

Media Ties

In general, however, fact-checking outlets rely on media attention as the most immediate proxy for their influence on public discourse. This is true to an extent even for reporters based in news organisations, who closely track the interest their work receives on social media and from other journalists. ‘I very regularly keep in touch with mentions on social media and any sort of citations that might come in the Irish Parliament, or any sort of promotion of a particular piece that might be done by other prominent journalists,’ said Dan Mac Guill of TheJournal.ie. For NGO-based outlets, meanwhile, coverage by established news organisations is the only vehicle for reaching a sizable audience and shaping public debate. In our survey, half of European fact-checking outlets indicated that they relied on the news media heavily (four or more on a scale of five) to increase the reach and impact of their fact-checking.

Fact-checkers employ a range of strategies to increase their media footprint, from standard media relations to producing stories with or for particular high-reach news organisations. First, nearly all independent or NGO-based outlets make staff available for interviews and work closely with outside journalists to promote their fact-checks. Organisations such as the UK’s Full Fact, Romania’s Funky Citizens, Serbia’s CRTA, and Turkey’s Dogruluk Payı see media relations as a core function, and cultivate a public profile for their senior staff.

Creative Commons licensing is popular in the NGO community, and many outlets actively encourage news organisations to republish fact-checks in their entirety. Macedonia’s Vistinomer uses a mailing list to promote its content and has 20 to 30 organisations who at least occasionally republish this work. The Conversation likewise invites wide redistribution. ‘All of our content is not only just free for anyone to take and republish, we have a team dedicated to encouraging that,’ said Megan Clement. ‘That’s a key part of it, you know, articles don’t finish when they get published on The Conversation because there’s so many other places they could go.’

A number of recurring concerns were voiced by fact-checkers who depend on outside news organisations to cover their work. In media environments dominated by partisan outlets, fact-checkers worried that their reputation would be stained by journalists who distort their work or cite it selectively. For instance, Bosnia’s Istinomjer has seen its articles selectively edited and reprinted by a newspaper owned by a party leader. ‘That was really potentially harmful for us,’ said Aida Ajanovic. ‘It made an impression like we were actually working for the paper because they would give us like the middle two pages … And in a very consistent manner, they omit all the things written about the party that owns this paper.’ In Macedonia, soon after Vistinomer launched, one opposition party unveiled a truth-o-meter that looked suspiciously similar but only fact-checked the ruling party.

Several fact-checkers complained that their work is sensationalised or misrepresented by journalists. ‘For the media to make it interesting they always use the term “lie”,’ said Zdenek Jirsa of the Czech site Demagog. ‘Then basically we have to write some sort of response, and clarify [that] we are not saying that the politician is lying, we are just purely stating that a fact is untrue.’ Another widespread concern is that news outlets take material without fully crediting the fact-checkers who produced it. ‘There’s a lot of ripping off,’ said Alexios Mantzarlis. ‘The better stories would end up on La Stampa even with scarce attribution.’ He recalled an instance in which Pagella Politica debunked a far-right claim that authorities were removing a piece of playground equipment shaped like a pig because it offended Muslim mothers, only to see their reporting, and their carefully verified photo of the playground, spread across Italian media. Practitioners in Serbia, Poland, Romania, and elsewhere agreed. ‘Basically what happens in Kosovo, because it’s such a fragile system, what all the media outlets do is they steal our news,’ said Faik Ispahiu. ‘It is a kind of flattery, but it is very frustrating.’

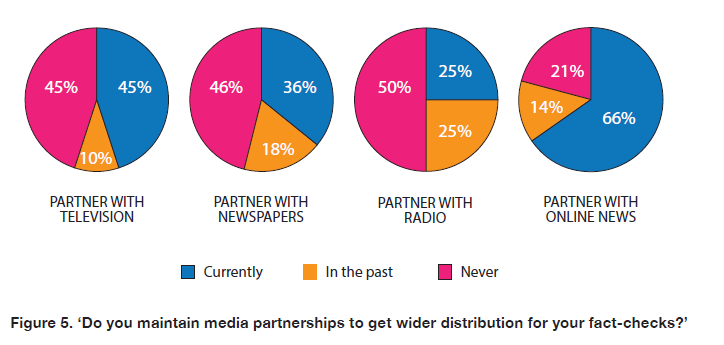

To exert some control over their media footprint most European fact-checking organisations rely on formal or informal media partnerships. In our survey, 54% indicated they currently partner with a newspaper or have in the past; 55% said the same about television, 50% about radio, and 80% about online news outlets. In rare cases, fact-checkers receive compensation from media partnerships: Italy’s Pagella Politica and the French outlet Désintox – despite being owned by a newspaper – have both relied on broadcast partnerships as a primary revenue source.

Normally, however, no money changes hands in these deals, which range from agreements to provide content or be interviewed regularly, to co-branded broadcast segments or newspaper sections that run on a fixed schedule. For example, every article by FactCheck Ukraine also runs on the country’s largest online tabloid, Ukr.net; the fact-checkers also appear roughly every two weeks on Espreso.TV, an online video news network, to discuss their work. Serbia’s Istinomer provides both fact-checks and media analysis pieces to N1, a regional, CNN-affiliated cable network, on a weekly basis. Romania’s Factual.ro has a partnership with Vice Media, which republishes selected fact-checks and matches them to sentiment analysis by a software firm which analyses facial expressions in recorded video – a kind of lie-detector test. The group also has a partnership with a prominent, Politico-like opinion site called Republica, and with a national radio network which offers a weekly fact-checking programme.

In some cases fact-checking outlets offer exclusive agreements to prominent media outlets. FactCheck Georgia partners with a number of regional TV networks and news sites, but has an exclusive relationship with Georgia’s leading national news site, NewPosts.ge, which reprints its articles in full and also features a ‘scroll’ on its home page controlled directly by the fact-checkers. VoxCheck offers individual exclusives to particular outlets depending on the article, in order to secure coverage across the media. In contrast, Full Fact avoids exclusives as a policy but still partners avidly. During the run-up to the Brexit vote in August, Full Fact’s articles ran on a blog published by the Daily Telegraph’s data journalism team; the fact-checkers also collaborated with the Financial Times, the Sun, and other papers for Brexit-related coverage. In addition, Full Fact partners with ITV News for live fact-checking of political debates, and has a new agreement with LBC Radio to deliver weekly video fact-checks featuring its analysts. Full Fact also has a new agreement with the Telegraph to carry its fact-checks of Prime Minister’s Questions, which also run on the Huffington Post.

In interviews many fact-checkers offered examples of the way that political considerations complicate the partnership landscape. For instance, FactCheck Georgia was approached in 2015 by one of Georgia’s biggest media houses, which was prepared to pay to carry fact-checks in its newspapers, TV networks, and online. ‘That made me crazy, that made me really happy,’ said Paata Gaprindashvili – until the deal collapsed after what appeared to be pressure from the ruling party. Istinomer had a distribution partnership with Serbia’s highest-circulation newspaper which fell apart for similar reasons. Baybars Örsek suggested that in Turkey’s politically charged media environment, Dogruluk Payı’s lack of a clear political position makes it a risky bet for major domestic media companies. ‘One of the obstacles we have is that since we are not affiliated with any political position in Turkey, TV channels are hesitating to invite us because probably they don’t trust us, and they don’t want to take the risk,’ he said.

Several fact-checking groups pointed to public media as their ideal partners, but few of these relationships exist and political pressure complicates those that do. The controversial nature of fact-checking created an opportunity for Pagella Politica when producers at Italian public broadcaster RAI wanted to experiment with the format, suggested Alexios Mantzarlis. ‘I think fact-checking, especially on a state TV, is a big bet to make, it’s a hard bet to make, I don’t think we’ve seen it in America done quite as big, and there are political pressures for that,’ he said. ‘And I think having outsiders do it kind of insulated RAI a little bit.’ However, the programme was cancelled after three seasons; a partnership with another RAI programme, Sunday Tabloid, began in September 2016. Meanwhile, Internews Kosova has not been fully paid by public broadcaster RTK for several years despite producing two of the most highly rated public affairs programmes on the state-run network, according to Faik Ispahiu, who believes the current government would like to see the programmes fail. ‘It’s a constant game of cat and mouse,’ he said. ‘One of the ways of pressuring us is the fact that they are not paying.’

Finally, it is important to note that many fact-checking organisations report becoming increasingly involved in media production in order to secure valuable partnerships or promote their work across new channels. For instance, its partnership with RAI essentially made Pagella Politica responsible for producing the fact-checking segment of the show, and even for providing the host. In addition, with funding from a Kickstarter campaign, in 2015 the site began creating animated versions of key fact-checks – starring a cartoon chicken named Pollock – to distribute on YouTube. Similarly, Serbia’s Istinomer produces a weekly series called Fakat, carried by the cable network N1 and on YouTube, which transforms fact-checks into two- or three-minute video montages featuring an animated truth-meter. StopFake produces weekly video digests for regional TV channels, available on YouTube in Russian and English, as well as a radio show distributed on SoundCloud and syndicated to radio partners. Dogruluk Payı uses a small in-house studio to produce a weekly podcast and occasional Facebook Live videos. In addition to producing a weekly, 16-page print newspaper – called simply Fact Meter – aimed at older Georgians, FactCheck Georgia has a small video production team which turns fact-checks into short, interview-driven video segments to distribute online and through TV partners.

Funding

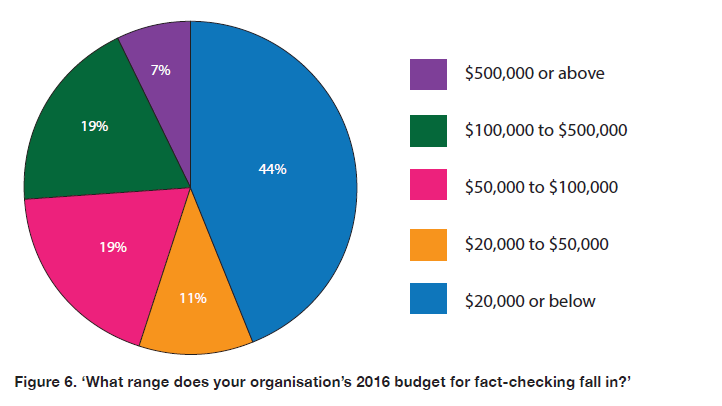

Two features stand out when considering how fact-checkers in Europe fund their efforts. The first is that budgets for these efforts span a wide range, but remain quite low for the typical outlet. In our survey, more than half of the organisations responding reported annual expenditures of $50,000 or less on fact-checking; for 44%, the figure was below $20,000. Meanwhile, just over one quarter had a fact-checking budget over $100,000. A worldwide survey by the Poynter Institute in May 2016 found similar results: nearly 45% of fact-checking budgets were below $20,000, while about 29% were greater than $100,000.

This range reflects economic variation across Europe but also the different approaches these organisations have developed. Full-time fact-checking by professional researchers in a wealthy country is an expensive proposition. Full Fact, supported mainly by foundation grants and individual donations, publicly estimates that costs will reach £600,000 in 2016. The Conversation UK, also a registered charity, reports 2016 expenditures approaching £1,000,000 (though fact-checking accounts for only a fraction of that). Private newsrooms don’t report their editorial budgets but the largest efforts, like Les Décodeurs and El Objetivo, clearly represent substantial staff investments.

At the other end of the spectrum, the fact-checking operation at TheJournal.ie amounts to the budget for one freelancer producing about two articles per week. The volunteer-driven Demagog sites have negligible budgets, with top editors receiving token compensation when grants are available. The three sites accomplish this by relying on universities for a steady supply of student volunteers, which in turn has required them to develop screening mechanisms and rapid training programmes to handle high turnover. They also control costs by coordinating all work remotely through their CMS. ‘If you don’t have to pay people, you’re basically – you have no limits,’ said Zdenek Jirsa, of the Czech site. ‘You can always get interns, because there are new students every year, and they are interested as well.’

The second point is that fact-checking across Europe depends above all on two financial anchors, the media industry and charitable foundations. In our survey, one-third of responding organisations relied on a media parent as a major funding source – typically the only one. Meanwhile, half listed private charitable foundations (like the Open Society Foundations) or state-sponsored funds (like the US-backed National Endowment for Democracy), or both, as primary funding sources. Notably, most of these are international, rather than domestic, funders. Again, this matches the global picture; the May 2016 Poynter survey found that the majority of fact-checkers get the majority of their funding from large grant-giving organisations.