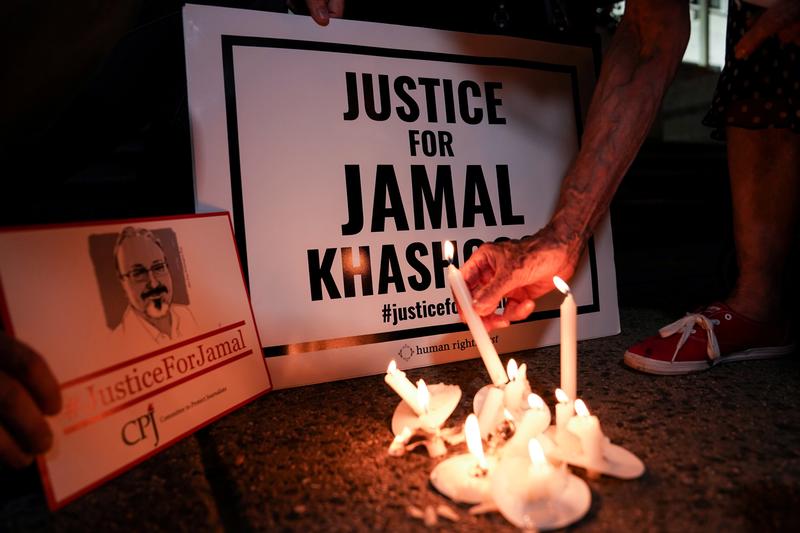

The Committee to Protect Journalists and other press freedom activists hold a candlelight vigil in front of the Saudi Embassy to mark the anniversary of the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the kingdom’s consulate in Istanbul, Wednesday evening in Washington, U.S., October 2, 2019. REUTERS/Sarah Silbiger.

This forward looking essay by Meera Selva supplements the Journalism, Media and Technology Trends and Predictions 2020 report. See menu for other such essays.

Politicians’ Attacks on Journalism

Journalists in 2020 will have to talk direct to their audience, to convince their viewers and readers that they are impartial, trustworthy, and deserving of support when politicians attack.1 The majority of the digital leaders surveyed say that news media should do more to call out misleading statements and half-truths by politicians. But to be able to do so effectively, they have to protect their independence and their connection with the public.

Governments, either tetchy or empowered, feel entitled to attack journalists as never before. Taking their cue from the President of the United States, political leaders are lashing out at journalists, with the assumption that they have the support of the public in doing so.

Journalists find themselves being trolled by activists from all sides of the political spectrum, subject to online attacks and accusations of bias and partisanship. Journalists, particularly women, must routinely cope with being abused and having their work distorted online.

And these attacks will go mainstream as more and more leaders, emboldened by Donald Trump, but also by Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Narendra Modi in India, and several governments in the European Union and across the world, normalise a culture of criticising and undermining journalists on social media. In Europe journalists warn of particularly virulent levels of trolling from far-right groups, who combine attacks on journalism with concerted misinformation campaigns.

Covering Protests and Polarised Politics

The role of journalists covering large-scale protests and demonstrations will also grow more complicated, as they become seen not as neutral observers but either participants and activists themselves, or somehow allied to the authorities the protestors are demonstrating against.

Journalists have been pepper-sprayed, teargassed, and detained by police in Hong Kong and are likely to continue to come under assault there as protests continue into 2020. The protestors, while largely supportive, are also suspicious that journalists are trying to reveal their identities to the authorities. In Bolivia they are under attack from the public and from police: a trend that will be seen more countries.

Even in long-standing liberal democracies, journalists are under attack from all sides of the political spectrum, with politicians and activists questioning the impartiality even of broadly trusted news media like public service broadcasters such as the BBC and Japan’s NHK, and populists of different persuasions painting ‘the media’ as part of an out-of-touch elite establishment.

Authorities Limiting Freedom of Expression

A raft of legislation ostensibly aimed at curbing misinformation and hate speech is likely to add an extra burden on journalists already battling vexatious defamation and libel suits. In the last year Russia and Singapore have both passed laws, ostensibly aimed at curbing misinformation, that put pressure on platform companies to monitor posts, and several other countries including Nigeria are likely to follow suit with similar laws this year.

There will also be a battle for access to public information and data. Journalists are braced for a slow erosion of Freedom of Information laws, undermining their access to information that should be widely available. This is likely to be accompanied by a tightening up of national security legislation, making it easier for governments to deem materials too sensitive to be released into the public domain.

But the biggest threat of all is silence. Governments around the world have begun hitting the mute button when the noise gets too loud, shutting off the internet when protests get too loud.

India dominates internet shutdowns. Kashmir will have been without the internet for 150 days as 2020 begins, and the government has shown it is willing to shut off the internet even in the capital city of Delhi amid protests against the new Citizenship Amendment Act and a proposed National Register of Citizens.

Meanwhile journalists in several sub-Saharan African countries are finding that new regimes can be as willing as the old to try to silence the national conversation. In Sudan, president Omar al Bashir stepped down after wide-scale protests over the price of bread and fuel, but the military regime that replaced him shut the internet down to curtail the pro-democracy protests that continued even after the regime change, and may do again. Zimbabwe’s new president Emmerson Mnangagwa shut down the internet after protests and has signalled he is as willing to use this particular form of cyber censorship as his predecessor Robert Mugabe.

Even in a long-standing liberal democracy like the UK, police have shut down wi-fi access in parts of the London Underground in an attempt to disrupt action by climate change protestors, marking a significant shift in thinking.

These internet shutdowns silence the social media platforms many people use to organise and receive news and which are also vital tools for journalists themselves to collect and disseminate information.

Journalists’ Response

Journalists are responding to these threats with debates and soul-searching on how to report on populist movements, when to give the leaders a platform to speak, and when they should be ignored. They believe the key to survival is to build trust with audiences and to explain to the public how journalism works.

Newsrooms will have to learn how to better support their reporters, who routinely face harassment and threats online and in real life, accepting the toll their work takes on journalists’ mental health and personal lives.

Media organisations must find a way to defend themselves, their principles, and their distribution channels, whether that be social media platforms, airways, or news sellers. It is no longer enough to say that the reporting will speak for itself. Journalism must be protected, defended, and strengthened in 2020 at every level if it is to continue to hold power to account. Journalists must build, maintain, and strengthen their connection with the public to be able to do their job.

Meera Selva is Director of the Journalism Fellowship Programme at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and an accomplished senior journalist with experience in Europe, Asia, and Africa. She joined the Reuters Institute from Handelsblatt Global. Her previous experience includes several years at the Associated Press and three years as Africa correspondent for the Independent, along with stints in business journalism at a range of publications, including the Daily Telegraph.

1 This essay, on threats facing journalists in 2020, draws on questions sent in December 2020 to the current set of RISJ fellows and summer school participants, and a forthcoming report to be published by the Reuters Institute.