| Statistics | |

| Population | 38m |

| Internet penetration | 68% |

Grzegorz Piechota

Research Associate, Harvard Business School

The Polish media environment is characterised by a highly competitive broadcasting sector and a group of large web portals. A political crisis has been driving interest in news since the elections in 2015 but has shaken the market too, as the conservative government has attacked both public and private media.

Despite mass street demonstrations supporting freedom of the press, the ruling Law and Justice party introduced a new bill on public radio and television in early 2016. The bill let the government seize direct control over the broadcasters, and purge their newsrooms (nearly 230 journalists have been sacked or have left in protest1). Radical changes in programming followed, with accusations of turning news shows into the government’s ‘fake news’ factories.

Viewers might have noticed the change, as their media diet appears to have shifted. According to Nielsen Audience, in 2016, the main state channels TVP 1, TVP 2, and TVP Info lost up to 10% of their average daily viewing shares vs. 2015, and up to 17% of viewers aged 16–49 – a major concern for advertisers (Polish state media is funded both by licence fees and advertising). The privately owned broadcasters have benefited, at least for now, as Polsat has taken over from TVP 1 as the most-watched general interest station, and TVN 24 has taken over from TVP Info as the top news channel.

State institutions and state-controlled advertisers have cut subscriptions and advertising spend in media outlets critical of the government, e.g. in Gazeta Wyborcza, the leading quality daily newspaper.2 Late in 2016, its publisher, Agora, laid off nearly 200 employees. These political pressures have dealt another blow to press publishers who had already been struggling with declining circulation and shrinking advertising revenues (e.g. all the national dailies have lost over 50% of print copy sales since 2007, according to ZKDP data).

Driven by anti-German sentiment, the Law and Justice party unveiled plans for another bill that would limit the share of foreign capital in the media business. So-called ‘repolonisation’, if enforced, could threaten investments of Ringier Axel Springer (an owner of the largest internet portal, Onet, and the biggest tabloid, Fakt), and Verlagsruppe Passau (a publisher of most regional newspapers and web portals across Poland via its subsidiary, Polska Press).

Many news consumers seek refuge online. Weekly episodes of Ucho Prezesa (The Chairman’s Ear), a political satire show launched on YouTube, featuring the Law and Justice party leaders, achieve up to 8.5 million views. For comparison, the most popular TV broadcast of 2016, live coverage of the Poland vs. Portugal football match, attracted 8 million people. New startups Oko.Press, BiqData.pl (by Gazeta Wyborcza) and TruDat (run by NaTemat.pl, a news portal) have pursued bold journalistic investigations, as well as verified statements by politicians and debunked fake news in the media.

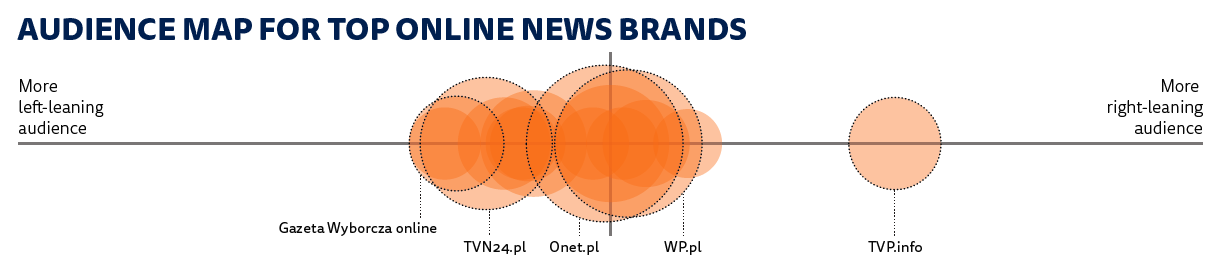

Online outlets have become the main source of news in the country in recent years, our survey confirms. Web portals like Onet and Wirtualna Polska reach half of the online population. Last year, the main portals invested heavily in original video production, hiring top talent from television and experimenting with new interactive formats like the morning live show Onet Rano. Aiming to further erode the business of large broadcasters, Wirtualna Polska and Agora (owner of a Gazeta.pl portal, besides its flagship newspaper’s site Wyborcza.pl) have also launched new terrestrial digital TV channels.

Some newspapers have recently crossed milestones unimaginable a few years back, e.g. Gazeta Wyborcza reported 100,000 active digital-only subscribers at the end of 2016. Popular bloggers have been testing paid content models too, with the launch of Patronite.pl, a crowdfunding platform for story-tellers. Meanwhile, many journalists have been excited by the success of Finansowy Ninja (Finance Ninja), a self-published book and a webinar project, by Michal Szafranski, a journalist turned a full-time blogger, who reported a €300,000 profit after eight months. Compare this to the median annual salary for a journalist in Poland of around €10,000.3

Changing Media

Polish audiences still rely on the computer and on portals more than smartphones when compared with other Europeans. Perhaps as a result new mobile messaging apps are also less popular than elsewhere.

Trust

Although polarised and increasingly partisan, the news media in Poland continue to be trusted by the public. First, many journalists and outlets are transparent about their world-views and motives, and attract audiences who think alike. Secondly, the public might respect journalists’ role in holding those in power into account at a time of erosion of other democratic institutions.

- Towarzystwo Dziennikarskie tracks purges in public radio and television in its ‘“Good change” in media’ online feature at http://towarzystwodziennikarskie.org (accessed Apr. 2017). ↩

- Neil Buckley, Long-Term Polish Dissident Braced for Fresh Battle. Financial Times (27 Jan. 2017): https://www.ft.com/content/f419ee4a-e3ab-11e6-9645-c9357a75844a (accessed Apr. 2017). ↩

- Statistics from Sedlak & Sedlak HR firm. ↩